In the case of pregnancy, the uterus and the embryo send hormones that help maintain the corpus luteum throughout the entire pregnancy.

One of the most important factors affecting the management of breeding is the length of this gestation period (the time the cow carries the calf from conception to birth). After calving, a cow should not be brought to the bull before at least 50 days have elapsed to allow the uterus time to undergo involution (a necessary period of rest and recuperation from possible injuries suffered at calving).

In herds where calving takes place in a restricted breeding season, a cow has a very limited period of time to fall pregnant. Adding 50 days to the 283 days of gestation and subtracting the total from 365 days, leaves the cow 32 days to conceive in time to calve the following year at approximately the same time of the year. On average a cow comes on heat every 21 days (heat lasts 6 to 18 hours), which means that she has at most 2 chances during these 32 days (often one chance only) to re-conceive.

Heifers are usually mated at either 15 or 27 months to calve down for the first time at 2 or 3 years respectively. As a rule of thumb, heifers should first be mated when they weigh at least 60% of their mature mass. The age at which this target mass is reached will differ depending on the level of nutrition (amount and type of feed available), breed, the age at which she cuts teeth and the time of year she was born.

First calf cows (i.e. heifers that have calved and are brought to the bull for the second time; by definition, a heifer becomes a cow at the birth of her first calf), have notoriously low conception rates, partly as a result of the fact that the inter-calving period between the first and second calf has been shown worldwide to be longer than subsequent inter-calving periods. Inadequate nutrition is probably a contributory cause of the extended first inter-calving period.

One of the strategies advised to overcome this difficulty is to breed heifers 4 to 6 weeks before the main herd. This practice compensates for the extended first inter-calving period and allows extra time between the first and second calf for the dam to build up body reserves as well as grow. It has been demonstrated that conception rates in first calves can be improved by breeding heifers ahead of the main herd, avoiding the imprudent loss of good genetic material where there is a policy to cull all skips (cows diagnosed non-pregnant at the time of pregnancy diagnosis).

Where first calves are run with the mature cows and/or if calves of first calves are not weaned before the main herd, the practice of mating heifers ahead of the mature cows does not achieve its aim of improving conception rates in first calves. If anything, failing to wean calves from heifers mated earlier, places additional stress on animals still in their growing phase. Another problem with breeding heifers ahead of the main breeding season is that the breeding season is timed to synchronise the available fodder production with the feed need of the mature cows. By breeding heifers earlier, their nutrient requirements are not matched to the fodder production of the farm unless supplemental feed for the heifers is provided. In practice, it could be better to breed heifers with the main herd and at the same time ensure that there is adequate feed for all the animals on the farm. Where heifers are mated with the main breeding herd, more heifers must be retained annually to compensate for the additional loss of first calves that do not re-conceive.

Keeping heifers and first calves in separate herds allows younger, growing animals access to better quality feed and an equal opportunity to reach feed or lick troughs.

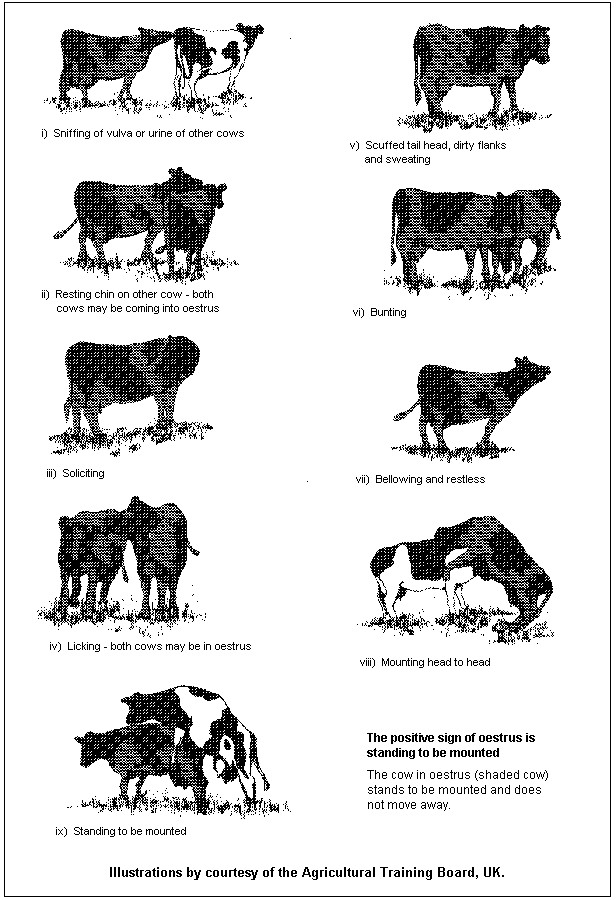

What are the Signs of Oestrus?

Oestrus is the physiological state during which a cow will stand to be mounted. The regular recurrence of mating behaviour (oestrus), together with changes in the reproductive hormones and genital organs, is referred to as the oestrus cycle.

Oestrus activity (ovarian activity with the production of oestrogen) normally recommences during the first three weeks after calving. The first observed oestrus (heat) occurs 3 to 6 weeks after calving, although there is a considerable variation between cows and herds. It is essential, however, to give the cow a voluntary waiting period (VWP) of 45 to 60 days after calving before rebreeding. This period is necessary for involution of the uterus, which may continue for up to 6 weeks after calving.

Involution is the shrinking of an organ (such as the uterus after pregnancy)

Oestrus Detection Aids

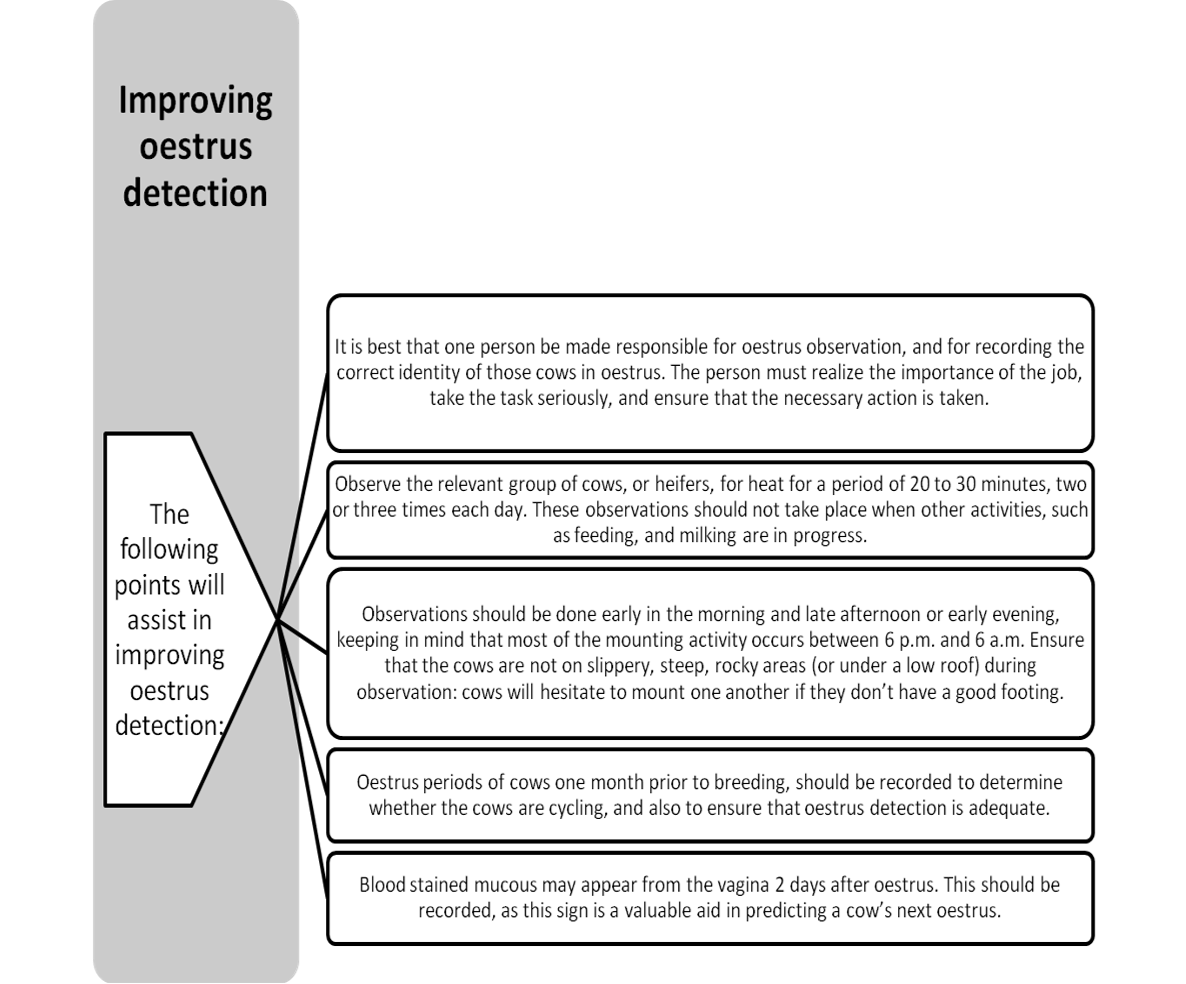

There is no real substitute for skilled observation, but heat detection aids can be useful. Listed below are some useful aids:

- The presence of a bull in the vicinity of the cows. This will stimulate oestrus behaviour in otherwise quiet cows. If the bull is placed in a pen sited in such a way that the cows can pass closely and regularly, those in oestrus will generally migrate towards the bull.

- Marker animals. Vasectomized bulls (bulls which have been surgically modified so that they are unable to fertilize cows but are still able and keen to mount them) or cystic cows can be used as heat detectors. If these animals are fitted with a “chin ball marker”, they will mark the backs of those cows which they have mounted.

- Heat mount detectors. These are pressure pads in the form of sachets, containing coloured dye, which are glued in place on the tailhead. The pressure exerted by a mounting cow on this pad on the back of a cow in oestrus induces a colour change in the dye. False positives do occur, for example, the banging or brushing of the detectors on obstacles such as cubicle rails. Their use is therefore best restricted to those cows which prove difficult to observe in oestrus.

- Tail “paint’. A well-placed strip of paint on the tailhead is a cheap and effective aid. This paint will be rubbed off or at least cracked when the painted cow is mounted by another. Again, false positives can be a problem, as in heat mount detectors. The technique demands good management, in the sense that cows should be checked at least once a day, otherwise heats might be missed.

An alternative approach to oestrus detection, namely the control of oestrus by the use of hormone-type administrations, is also available. In this way oestrus synchronization can be obtained, and insemination done at a fixed time without visual confirmation of oestrus. This technique is commonly used by veterinary surgeons for the treatment of individual cows or groups not observed in oestrus by the required time. It must be stressed that, although oestrus control enables cows to be inseminated at the optimum time, it does not improve the chances of conception/pregnancy. These synchronization techniques, used on heifers under good management, have consistently given conception rates of 60 to 70%. Much poorer results have been obtained in lactating cows. Remember that synchronization is not generally used as a blanket treatment for all dairy cows. If this technique is used, then the farmer must ensure that factors which are likely to affect conception rates, e.g. nutrition and body condition are checked.

Click here to view a video that explains Estrous cycle of cattle.