For a negotiation to start, there must be an opening statement. This is a vital moment in the negotiation and must be planned very carefully.

The opening statement not only tells the other party what you want, but how you intend to negotiate to get to it. If the opening statement is too weak, the other party will quickly realise that they can “win” the negotiation. If the statement is to strong, the other party may be offended, which creates a bad climate, or they might even decide not to negotiate at all.

Remember: People are likely to take a ‘position’ (their tangible wants). To move forward collaboratively, concentrate on what has made them take that position.

During the early stages of the negotiation, it is important to obtain information. This is usually information, but it may also include how people feel about the situation, as well as long term goals and intentions. Usually, a lot of information will be given out readily, but neither party can assume that they will get all the information they need or want.

Statements almost always reveal more than they intend. For instance, if Vusi says we need another 1000 customers per week, he is revealing that they already have a lot of customers by the word 'another'. If Vusi later says they are trying to grow by 25%, then by implication 1000 customers would represent 25%, which means he currently has about 4000 customers. Note that Vusi never said this, but the Hercules teams were able to deduce this by listening carefully.

One needs to listen for inconsistencies, gaps, and contradictions in what the other party says.

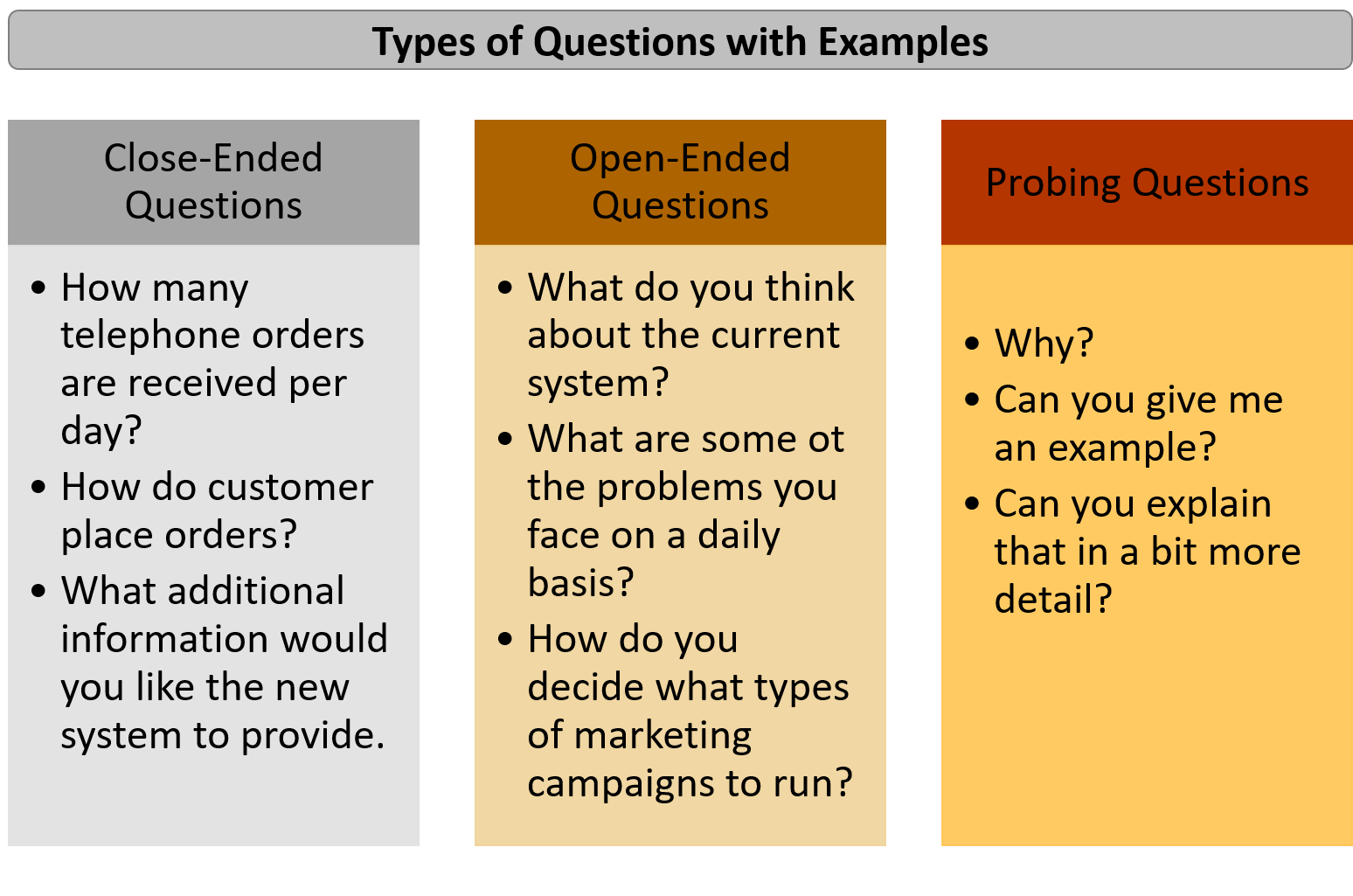

Secondly, various kinds of questions need to be asked. Some of the possible types of question are:

Closed, where a specific answer is requested: “What was your profit last year, according to the audited balance sheet?”

Open, where a range of answers is possible: “Why do you wish to expand if you are currently making a healthy profit?”

Hypothetically, where something that is not a reflection of current reality is posed: “If we gave up our demand for three deliveries per day, what could you offer?”

Probing, where gaps in inconsistencies are tested: “You said you did not have enough staff to make three deliveries, but you also say you want to expand – can you explain how you intend to expand if you do not have enough staff?”

If you don’t understand their answers, re-phrase the question or say you don’t understand. Use checking or summarising questions to be certain that you have understood: “If I have understood you correctly, you specifically need … Have I summarised this accurately?”

End this part of the negotiation by asking a closed question (one that invites a single word answer; a ‘Yes’ or ‘No’): “Is there anything else to be negotiated?”

So, in the discovery phase: ask a sequence of questions: open, specific, checking, summarising, and then closed.

And to get the process moving: give a little information, ask for some in return. Don’t be fearful of being the first to speak.

But all this is useless; whatever style of negotiation you use, unless you listen carefully to the answers!

And this includes listening carefully for what is not said or what might be an incomplete or evasive answer. For instance: ‘I think that’s all I need’ or ‘That’s all for now’. Follow up such responses to discover their underlying meaning.

If you are adopting a collaborative style:

You must also reveal all your tangible and emotional negotiables, your non-negotiables, and your success criteria in this phase.

Since you will be so well-prepared, you could perhaps just read through your list. But it would be better (i.e. less intimidating and less smug) to allow others to ask questions to elicit the information from you.

You should not move on in the negotiation until everyone’s information has been shared to prevent later surprises – unless, that is, you are being a tough negotiator!