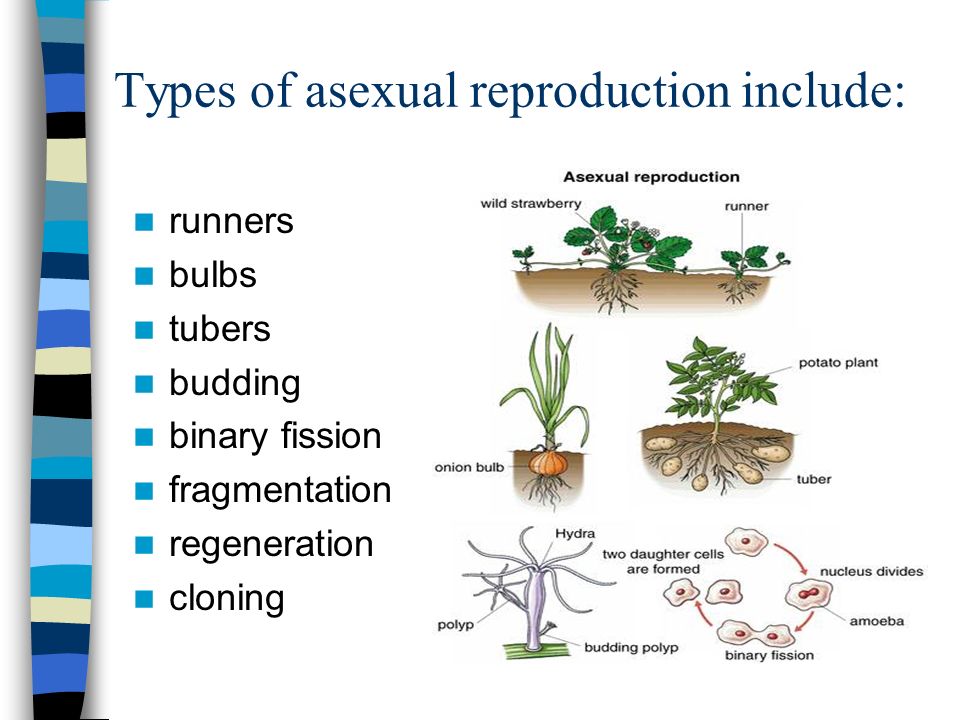

Asexual propagation is the production of plants using the vegetative parts of a plant. Vegetative parts include stems, leaves, roots, bulbs, corms, tubers, tuberous roots, rhizomes, and undifferentiated tissue often used in micropropagation. Propagation by division, cuttings, layering and grafting are all forms of asexual propagation. Although many plants can be propagated by at least one asexual method, there are some that for one reason or another can not. When compared to sexual methods, asexual methods have certain advantages.

- Plants are genetically identical to their parents so plants with desirable characteristics can be reliably cloned.

- It allows the propagation of plants that do not produce seed, produce little seed or are difficult or impossible to grow from seed.

- A grower can get a saleable or mature plant more quickly for many plants.

Some disadvantages include:

- Asexual methods are generally more expensive.

- Many asexual methods require greater skill, and/or special equipment or facilities.

- There is an increased likelihood of spreading or perpetuating certain diseases.

- Clones can become weakened and lose vigour after years of asexual production, although this is by no means a general rule.

Click here to view a video that explains asexual reproduction.

Division

Dividing plants is probably the simplest form of asexual propagation. This method is regularly used in the propagation of a wide range of herbaceous perennials such as daylilies, Siberian iris, bee balm and ornamental grasses. It essentially involves splitting a single large plant with many crowns or growing points into several individual smaller plants. It is labour-intensive, and for that reason is the last option for commercial nurseries when there is no other viable method of propagating a particular plant.

Cuttings

Cuttings can be taken from a variety of plant parts – stems, leaves, roots, buds – but not all plants can be propagated by cuttings and certainly few, if any, can be grown from all types mentioned. The plant from which the cuttings are taken is referred to as the stock plant or parent plant. There are many factors that affect the type of cutting used as well as the success achieved with a certain type of cutting and include:

- The type of plant being considered for propagation,

- The age and health of the stock plant,

- The time of year, and

- The facilities, equipment and material available for propagation.

When taking any type of cutting, keep in mind that by removing the cutting from the parent plant, it is cut off from its supply of moisture and is instantly under stress. This is a particularly important consideration when dealing with leafy cuttings such as herbaceous, softwood and semi-hardwood cuttings. To reduce stress on the cuttings, take cuttings on cool, cloudy days; place cuttings in a plastic bag along with a damp paper towel until they can be inserted in the rooting medium, and prepare cuttings quickly. Also, make sure that cuttings are labelled with the plant name, the date taken, and any special treatment given the cuttings, such as a particular hormone used. This can help you learn more about a plant and may be useful if you want to take cuttings again next year.

The rooting medium used can vary greatly from grower to grower and may vary depending on the type of plant being propagated. The medium must provide support for the cutting to keep it upright. It must also hold an adequate amount of moisture and allow for oxygen to reach the root zone. Although rooting media are similar to seed sowing mixes, they are generally coarser. A mix of half peat moss and half perlite is commonly used, but many mixes exist to meet the needs of different plants, or simply produce good results for the nursery or gardener using them.

Water is the most critical aspect in the rooting process – too much and the cuttings are deprived of oxygen and the likelihood of disease is greatly increased, too little and the cuttings suffer, wilt and will root slowly, if at all. Professional growers and nurseries use mist or fog systems to maintain ideal moisture and humidity levels. These systems are controlled by a humidistat, timer, or a unit called an electronic leaf.

Light is also an important factor, at least for stem cuttings with leaves and leaf cuttings. Light is necessary for these types, so the plant can continue to photosynthesize and produce carbohydrates needed for the development of roots. Too much sunlight, however, is to be avoided as this can cause the cuttings to dry out too quickly. The temperature can also have an effect on root formation. Good success can be achieved with an air temperature of around 65°F for a wide range of cuttings. Often, roots will form even more quickly if bottom heat maintains the rooting media about 10°F warmer.

Auxins are one class of plant hormones that occur naturally in plants. Rooting hormones used by propagators are synthetic versions of these compounds. Used correctly, these types of hormones can hasten to root, lead to denser root systems and help avoid certain disease problems. They are available as liquids or powders and vary in their concentrations of the active ingredients. The bases of stem cuttings are dipped into the material and then inserted in the medium. Two common rooting hormones are naphthalene acetic acid, (NAA), and indolebutyric acid, (IBA). Care should be taken when using hormones as certain cuttings can be damaged by the incorrect strength. These materials break down quite quickly in light, so they should be stored in an appropriate manner.

Types of Cuttings

Stem cuttings are certainly the most important type of cuttings in regard to commercial plant production. They can be divided into four groups based on the nature and maturity of the piece of the stem used – hardwood, semi-hardwood, softwood and herbaceous. With the exception of hardwood cuttings which are often longer, cuttings of approximately three to five inches are ideal, although cuttings taken from certain dwarf plants will necessarily be shorter.

When taking cuttings work with a clean, sharp, knife or hand pruners. Cuts should generally be made just below a node, (the point at which a leaf joins the stem, and the point at which roots form most readily), and the leaves on the lower one-third to one-half of the stem should be removed prior to insertion into the media. Basic cutting is referred to as simple or straight cutting. Heel cuttings are made by breaking a small, young shoot from the side of a branch. This will keep a small portion of the stem attached to the cutting. Mallet cuttings are similar but have a complete cross-section of the main stem. Some evergreens root better when heal or mallet cuttings are used.

Wounding the base of cuttings of certain plants such as rhododendrons, hollies, magnolias and others can promote root production. Wounds are generally made by stripping lower leaves and some bark from the cutting or by cutting off a thin slice of bark from the lower third of the cutting.

Leaf cuttings and leaf bud cuttings are useful for propagating plants such as African violets, snake plants, piggy-back plants and some begonias. A section of a leaf, the entire leaf or the leaf and associated bud are inserted into a typical cutting media. In all cases, the cutting does not become a permanent part of the plant, but gradually disintegrates after the new, young plant is established.

A fairly wide range of plants can be propagated by root cuttings. Oriental poppies, certain species of phlox and roses, blackberries, raspberries, Japanese flowering quince among others are all likely candidates for this method. The biggest drawback to this technique is that it involves digging the parent plant out of the ground, or at the very least, severing much of the root system to get at the necessary root pieces. Root pieces can be from 1-6 inches long depending on how coarse the roots are – the finer the roots the shorter the segments. If root cuttings are inserted into media vertically it is essential that they avoid being put upside down, thus maintaining correct polarity. In other words, the end of the root closest to the crown of the plant should be up and the farthest point should be down. Root cuttings of some plants can be laid horizontally, sidestepping this problem altogether.

Bulbs are specialized organs with a growing point surrounded by thick fleshy scales. Tulips, onions, lilies and daffodils are all bulbous plants. Techniques for propagating bulbous plants include scaling, basal cutting, offsets and micropropagation.

Layering is yet another form of asexual propagation and is a method that encourages the development of roots on a stem while it is still attached to the parent plant. Tip layering involves bending a branch to the ground, wounding the branch where it touches the ground and covering it with some soil. Roots develop and soon send out new shoots. At this point, the new plant can be cut off from the stock plant, lifted from the ground and transplanted. Black and purple raspberries, forsythia, spirea and many other common shrubs can be grown from tip layers.

Air layering is a similar technique but is a bit more involved and is used when a branch cannot be bent to the ground. This technique can be used to propagate several tropical and sub-tropical trees and shrubs such as croton, rubber trees, and philodendron. The stem is wounded, and the wound is covered with a generous amount of long-fibered sphagnum moss. The moss is then wrapped in a sheet of plastic that is tied off above and below the wound. The new plant can be cut off and planted once roots are visible through the plastic.

Click here to view a video that explains the air layering of trees.

Underground Structures

Many plants produce specialized structures beneath the soil that are generally used as food storage organs on which the plant relies during adverse growing conditions. Bulbs, corms, tuberous roots, tuberous stems, tubers, rhizomes and pseudobulbs are all such organs. Frequently, though technically incorrect, all or several of these structures are referred to as “bulbs.” To the propagator, they are often convenient means of producing plants that have developed these sorts of structures.

A corm is made up of the swollen base of a stem surrounded by dry, scaly leaves. Crocus and gladiolus grow from corms. Corms are propagated by inducing the natural reproduction of new corms and by the cultivation of cormels, which are also naturally produced during the plant's life cycle.

A rhizome is a specialized stem structure that grows at or just below ground level such as in bearded Iris, lily of the valley, sugar cane and many types of grass. Typically, they are easily propagated by simple division or by a special type of cutting.

A tuber is a swollen stem structure that serves as an underground storage organ with nodes, often called eyes, from which shoots emerge. The potato, Jerusalem artichoke and caladiums are all tuber-producing plans. Tubers are easily propagated by dividing them into sections, with each section containing at least one eye.

Pseudobulbs, (meaning, “false bulb”), are typical storage structures of members of the orchid family. Pseudobulbs are readily separated from the parent plant as a means of propagation.

Grafting and Budding

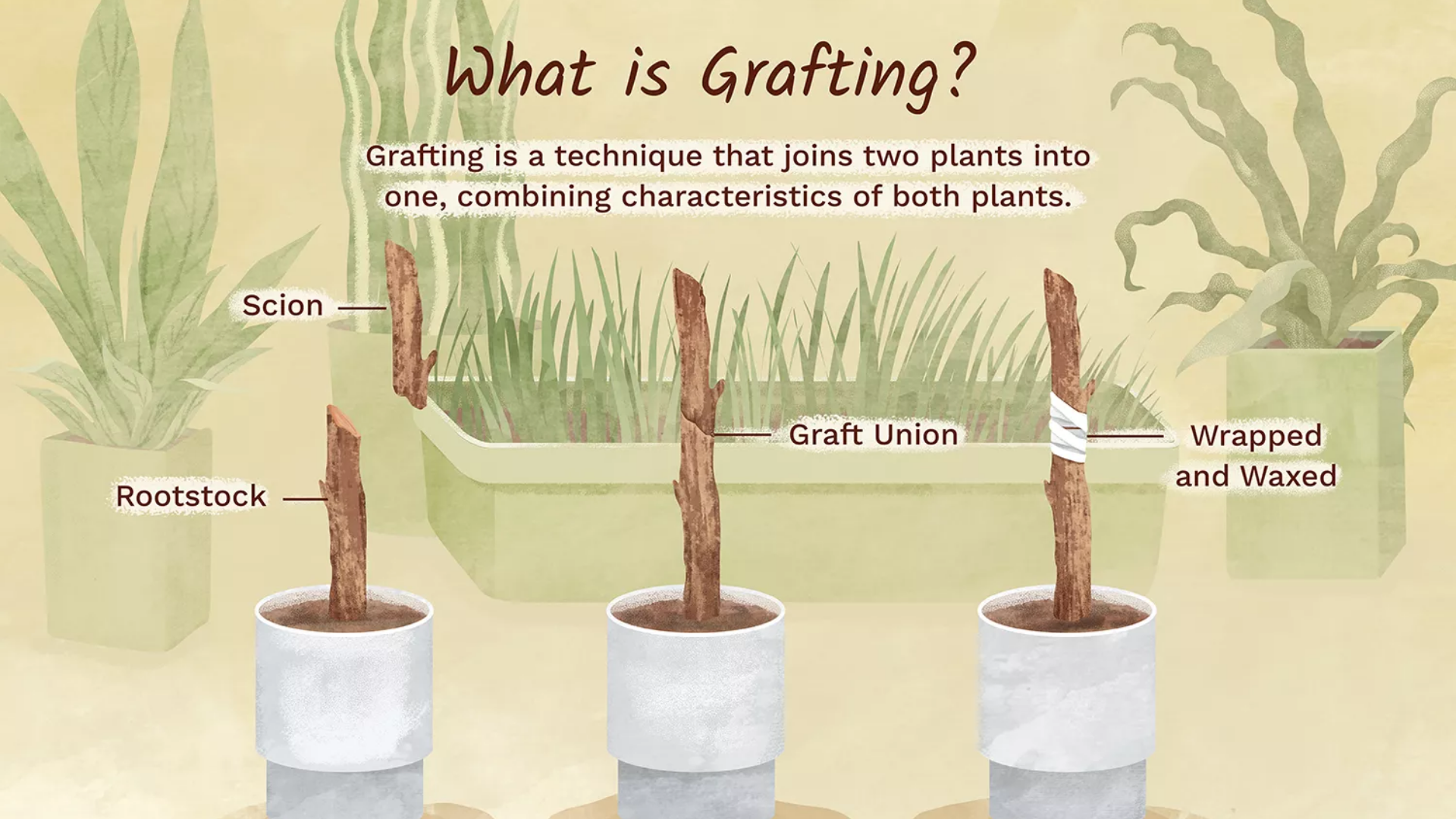

Grafting and budding are both forms of asexual plant propagation. They both consist of connecting two pieces of living plant tissue in a way that allows the parts to unite and subsequently grow and develop as a single plant.

In any form of grafting, a piece of stem or shoot with dormant buds is the part that will grow and develop with branches. This part is known as the scion. In budding, the scion is reduced to a single bud with an attached pad of bark and cambium. The part of the graft that will develop into the root system is known as the stock, rootstock or understock. The stock can be comprised of a root system, a sapling or, for the purposes of top working, a mature tree that has been reduced to a trunk and main scaffold branches. Fruits and nuts, as well as roses, lilacs, dwarf conifers and many ornamentals with unique habits, are examples of plants that are frequently grafted.

Click here to view a video that explains what is grafted plants?

There are several different types of grafts – splice, whip, cleft, approach, wedge, and others are all variations that have different applications for different situations and reasons for wanting to graft in the first place.

The reasons for grafting are quite varied and, among others, include:

- To perpetuate clones that cannot be propagated or are not easily done so by other methods.

- To obtain the benefits of certain rootstocks, such as to control height, habit or vigour, or to impart disease resistance.

- To change the cultivar of established plants through a technique known as top working.

- To obtain special growth habits or forms.

- To repair damaged parts of trees.

Click here to view a video that explains field whip and tongue grafting.

There are, however, certain disadvantages:

- It is frequently more expensive.

- Grafting and budding are fairly specialized skills, thus require great experience to be able to make grafts.

- Diseases are readily transmitted.

- Rootstock suckers can be troublesome and can weaken the growth of the scion.

Not just any scion and stock can be grafted successfully. The two parts must be from closely related plants. Plants from different families are incompatible and this is frequently true for plants in different genera within the same family. A scion and stock that can be successfully grafted are said to be compatible. A pairing that is incompatible will simply not grow or will grow but never form a successful graft union leading to failure sometimes years from the time when the graft was first made. The time of year can also play a role in the success or failure of a graft. One technique that is sometimes employed to overcome the problem of incompatibility is to use an inter-stock. An inter-stock is a piece of stem inserted between the scion and stock that forms graft unions with both. An inter-stock is also useful, in some cases, for imparting hardiness or a growth-regulating property.

When it comes to the actual act of grafting, the most critical point is that the cambium layers in the scion and stock be in close contact. The cambium is a layer of cells between the bark and the heartwood. This layer of cells is capable of dividing and forming new cells, forming callus in the process, which is necessary in order for the graft to be successful. It is important that the cambium layers do not dry out during the grafting process. The graft union is where the scion and stock are joined.

Click here to view a video that explains the cambium layer of the plant.