The Project Management Institute has attempted to determine a minimum body of knowledge that is needed by a project manager in order for him or her to be effective. There are five processes defined by the PMBOK, together with nine general areas of knowledge. A complete document can be obtained from the PMI website: www.pmi.org.

Click here to view a video that explains PMBOK Project Management Body of Knowledge.

Project Processes

A process is a way of doing something. The PMBOK identifies five processes that are used to manage projects. Although some of them will be predominant at certain phases of a project, they may come into play at any time. Broadly speaking, however, they tend to be employed in the sequence listed as the following project progresses: initiating is done first, then planning, then executing, and so on. In the event that a project goes off course, re-planning comes into play, and if a project is found to be in serious trouble, it may have to go all the way back to the initiating process to be re-started.

Initiating

Once a decision has been made to do a project, it must be initiated or launched. There are a number of activities associated with this. One is for the project sponsor to create a project charter, which would define what is to be done to meet the requirements of project customers. This is a formal process that is often omitted in organisations. The charter should be used to authorise work on the project, define the authority, responsibility and accountability of the project team, and establish scope boundaries for the job. When such a document is not produced, the team may misinterpret what is required of them, and this can be very costly.

Planning

One of the major causes of project failures is poor planning; actually, most of the time the problem is due to no planning! The team simply tries to “wing it”, to do the work without doing any planning at all. Many people are task-orientated, and see planning as a waste of time, so they would rather just get on with the work. As will be seen when dealing with controlling the project, failing to develop a plan means that there can be no actual control of the project.

Executing

There are two aspects to this process. One is to execute the work that must be done to create the product of the project. This is properly called technical work, and a project is conducted to produce a product. Note that the word product is being used in a very broad sense. A product can be an actual tangible piece of hardware or a building. It can also be software or service of some kind. It can also be a result: consider; for example, a project to service an automobile, which consists of changing the oil and rotating the tires. There is no tangible deliverable for such a project, but there is clearly a result that must be achieved, and if it is not done correctly, the car may be damaged as a result.

Executing also refers to implementing the project plan. It is amazing to find that teams often spend time planning a project, and then abandon the plan as soon as they encounter some difficulty. Once they do this, they cannot have control of the work, since without a plan there is no control. The key is to either take corrective action to get back on track with the original plan, or to revise the plan to show where the project is at present or continue forward from that point.

Monitoring and Controlling

These could actually be thought of as two separate processes, but because they go hand-in-hand, they are considered as one activity. Control is exercised by comparing where project work is to where it is supposed to be, then taking action to correct for any deviations from the target. Now the plan tells where the work should be. Without a plan, you don’t know where you should be, so control is impossible, by definition.

Furthermore, knowing where you are, is done by monitoring your progress. An assessment of the quantity and quality of work is made, using whatever tools are available for the kind of work being done. The result of this assessment is compared to the planned level of work, and if the actual level is ahead or behind the plan, something will be done to bring progress back in line with the plan. Naturally, small deviations are always present and are ignored, unless they exceed some pre-established threshold, or they show a trend to drift further off-course.

Closing

In too many cases, once the project is produced to the customer’s satisfaction, the project is considered finished. This should not be the case. A final lessons-learned review should be done before the project is considered complete. Failing to do a lessons-learned review means that future projects will likely suffer the same headaches encountered on the one just done.

Knowledge Areas

As previously mentioned, the PMBOK identifies nine knowledge areas with which project managers should be familiar in order to be considered professionals. These areas are the following:

Project Integration Management: Project integration management ensures that the project is properly planned, executed, and controlled, including the exercise of formal project change control. As the term implies, every activity must be coordinated or integrated with every other one in order to achieve the desired project outcomes.

Project Scope Management: Changes to project scope are often the factors that “kill” a project. Scope management includes authorising the job; developing a scope statement that will define the boundaries of the project; subdividing the work into manageable components with deliverables; verifying that the amount of work planned has been achieved; and specifying scope change control procedures.

Project Time Management: Project Time Management includes the process required to ensure the timely performance of the project. It consists of activity defining, activity sequencing, duration estimating, schedule development and time control.

Project Cost Management: This is exactly what it sounds like. It involves estimating the cost of resources, including people, equipment, materials, and such things as travel and other support details. After this has been done, costs are budgeted and tracked to keep the project within that budget.

Project Quality Management: One cause of project failure is that quality is overlooked or sacrificed so that a tight deadline can be met. It is not very helpful to complete a project on time, only to discover that the thing delivered won’t work properly! Quality management includes both quality assurance (planning has to meet quality requirements) and quality control (steps taken to monitor results to see if they conform to requirements).

Project Human Resource Management: Managing human resources is often overlooked in projects. It involves identifying the people needed to do the job, defining their roles, responsibilities, and reporting relationships, acquiring those people, and then managing them as the project is executed. Note that this topic does not refer to the actual day-to-day management of people. PMBOK mentions that these skills are necessary but does not document them.

Project Communications Management: As the title implies, communication management involves planning, executing, and controlling the acquisition and dissemination of all information relevant to the needs of all project stakeholders. This information would include project status, accomplishments, events that may affect other stakeholders or projects, and so on. Again, this topic does not deal with the actual process of communicating with someone. This topic is also mentioned, but not included, in PMBOK.

Project Risk Management: Risk management is the systematic process of identifying, quantifying, analysing and responding to project risk. It includes maximising the probability and consequences of positive events and minimising the probability and consequences of adverse events to project objectives. This is an extremely important aspect of project management that is sometimes overlooked by novice project managers.

Project Procurement Management: Procurement of necessary goods and services for the project is the logistics aspect of managing a job. It involves deciding what must be procured, issuing requests for bids or quotations, selecting vendors, administering contracts, and closing them when the job is finished.

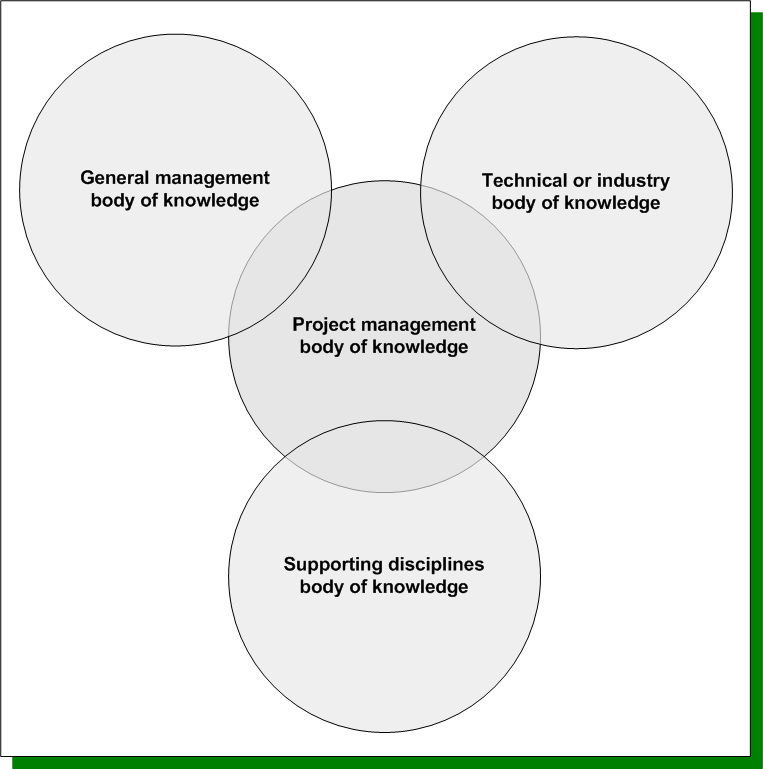

The relationship between project management and general management is illustrated in the diagram below: