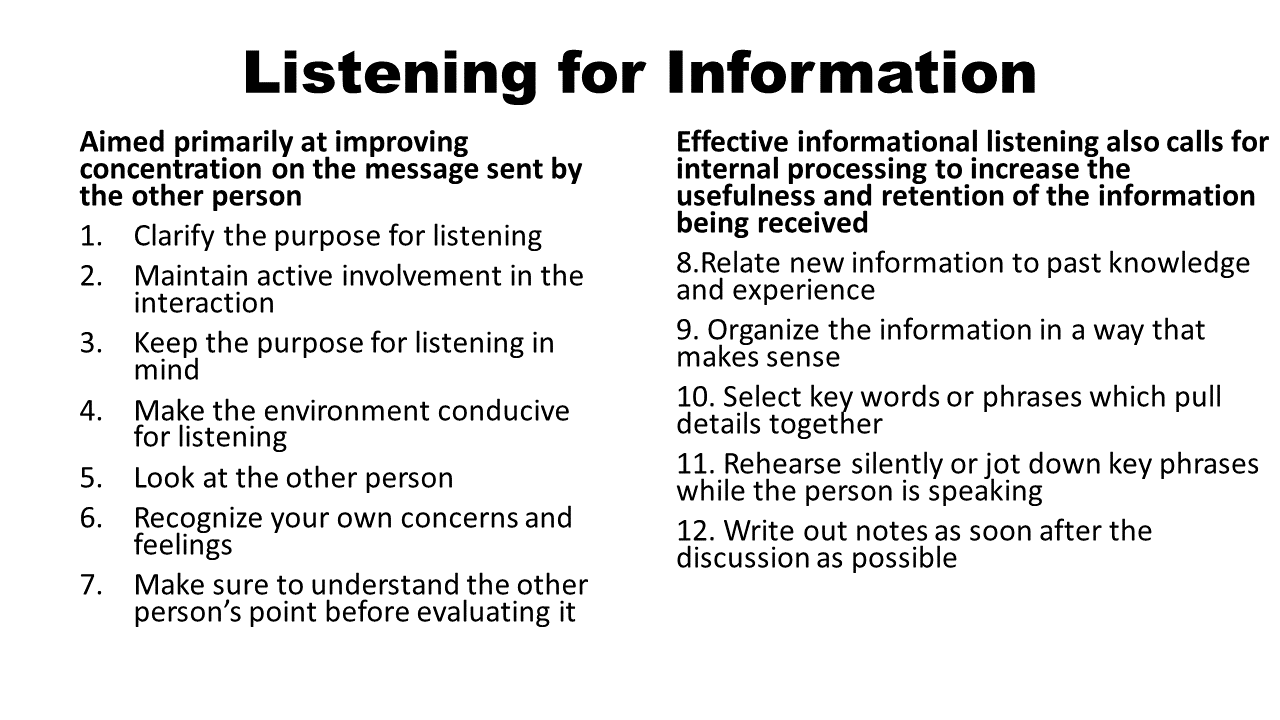

Research has shown that the quality of listening for information is related to our intelligence, motivation, and listening habits. We probably cannot improve interpersonal listening by becoming smarter, but we can make significant improvements in motivation and listening habits.

Clarify the purpose for listening: You will not be motivated to listen if you believe that the information given by the other person is unhelpful or irrelevant. You may need to let the person know what your purpose is: "Could you explain X to me?" "I want you to tell me how to X correctly." "I’d like you to describe what happened." If the other person initiates the information, then ask about his or her purpose: "What is your purpose in telling me this?"

Maintain active involvement in the interaction: When we feel involved, the process of interacting with others is enjoyable. When we feel uninvolved, the danger of daydreaming and pseudo-listening increases. Involved listening requires giving feedback. Feedback can improve the quality of information, which the other person provides. Nonverbal cues and back channel comments ("yes," "uh-huh") shows interest, paraphrasing material clarifies understanding, and asking questions to bring out further information. Often it is important for us to make comments about the information and to reveal relevant information of our own.

Keep the purpose for listening in mind: The purpose will help focus our attention on what is important. It will also help monitor the direction of the discussion. We can then steer the discussion back on tract and in productive directions: "A few minutes ago you were saying X; I’d like to know a little more about that." The guidelines above will help maintain motivation for listening and quality of interacting. Motivation itself is a major factor in concentration, and will help listen effectively even under adverse conditions. However, more steps may be taken to increase concentration:

Make the environment conducive for listening: The optimal environment feels pleasant, allows us to sit as close as is comfortable to the other person, features few distractions, and places us out of hearing of others who are not part of the interaction. If the selected environment is too distracting, change position, remove the distraction, or suggest a different environment.

Look at the other person: An important part of the other person’s message is sent through nonverbal communication. Looking at the person helps receive the entire meaning. In addition, it avoids potential outside distractions and signals interest to the other person, as discussed above.

Recognize your own concerns and feelings: Outside concerns which we bring to the discussion may compete for our attention. Feelings aroused by the other person may threaten to distort the message. Concerns and feelings will not go away by attempting to ignore them. If the situation is informal and we know the other person well enough, discussing our concerns and feelings is an effective way of managing them. However, just silently recognizing and accepting that they are there is a helpful step toward to listening through them.

Make sure to understand the other person’s point before evaluating it: Critically analysing ideas and information is important, but not while the person is speaking. Arguing in our minds or preparing responses while the speaker is talking are habits which interfere with our concentration on the message. A critical response will form as we begin our turn to speak. The preceding suggestions are aimed primarily at improving concentration on the message sent by the other person. Effective informational listening also calls for internal processing to increase the usefulness and retention of the information being received.

Relate new information to past knowledge and experience: That does not mean distorting new information to fit prior expectations; in fact, it may mean contrasting it with what we already know. The point is that information is not useful or memorable in a vacuum; we must tie it to things we already know. When the details are descriptive, visualizing them also helps remember them.

Organize the information in a way that makes sense: People often talk in a stream of consciousness. The apparent connections between pieces of information may be understandable at the time, but these connections quickly evaporate from our memories. If the information is reorganized in relation to a familiar pattern, such as time, space, or a learned system of concepts, it will be more useful and memorable and help guide our questions and feedback.

Select key words or phrases which pull details together: It’s usually a mistake to try to remember everything that another person says. Short-term memory does not hold much; new details tend to push out the ones which came just before. We remember more immediately afterward if we recall key phrases. Trying to keep everything in mind leads to frustration and the possibly of giving up listening.

Rehearse silently or jot down key phrases while the person is speaking: In many interpersonal situations, taking notes would appear rude or suspicious. In those situations, silent rehearsal and verbal paraphrase are the best ways to retain the information until you have a chance to write it down. However, even when note taking is acceptable, such as in a formal interview, extensive notes hurt concentration and rapport with the other person.

Write out notes as soon after the discussion as possible: No matter how vivid the key phrases are, the associated detail will begin immediately to fade from memory. If the details are important to remember, they must be written down for future reference and study.

Questioning

Having established the initial contact with your client, and listened to their query, your first response will be to question him/her to ensure that you have understood the query correctly and to reach consensus for further action. With relevant, insightful questions you will be able to manage the client interaction and reach a conclusion.

The ask and listen stage of the client interaction can be thought of as "examining the patient." If you expect to be respected as a professional, it's a step you can't skip or even gloss over. Take time to learn the different types of questions and practice using them. By developing your questioning skills, you will build credibility with you clients and enhance the client image of your organisation.

Types of Questions For Client Relationships

There are two main dimensions to questions: Openness and Directness. Openness ranges from open questions, where there are unlimited response possibilities, to closed questions where response is limited to yes, no, or a few options. Directness ranges from totally direct where the intent of the question is obvious, to Indirect where intent behind the question is not so apparent. Another factor affecting questions is bias. Biased questions have only one right answer, which exposes to clients that the question is really not a question at all. Instead it is a manipulative way of getting the client's agreement.

Click here to view a video that explains closed vs. open questions.

Closed Questions

While open questions have a whole choice of possible responses, closed questions limit the possible responses to a simple one-word answer like yes, or no, a number (policy number, date of birth, etc), or to a few options, like today or Thursday. Closed questions often begin with: Do, Are, Is, Which, Have. "How many," and "How often".

Although closed questions limit possible responses, they have several uses and can be extremely useful in the hands of the right person.

- In the Financial Services environment, we usually use them to verify who the client is and if they are entitled to the policy information. E.g. “what is your policy number, your date of birth, identity number, your address”

- It is also used to help focus the client back to business. E.g. "This is very interesting, but can I help you resolve your concern?"

Closed probes can also be used to confirm your understanding of a point your client has made or to confirm needs.

You might ask:

- "Then, we can assume you will deposit last month’s contribution today, right?"

- "If I understand you then, you'd like to take additional medical cover without increasing your contribution, is that accurate?"

When you ask questions to confirm needs, your questions should be asked so that your client can answer with a yes or no response”

- "Would you be interested in?"

- "Will it be important to you to?"

- "Do you want to?"

When you need specific information, closed questions are effective.

- "How many times did you try to contact your agent?"

- "On what date were you burgled?"

- “What is your new address?”

Open Questions

Open questions typically begin with words like: what, how, why, where, who and how. They can also be statements.

- "Can you tell me more about?"

- "What happened when?"

- "How did you hear about?"

You will typically use open probes to explore your client's situations and to identify needs. They are great icebreakers to get people talking. They are especially advantageous, because they are open to a large range of responses, indicating what's on the client's mind.

Open probes can also be used to clarify your understanding of what your client has said. When you clarify, you ask questions to understand what your client has said and why he or she has said it.

Direct vs. Indirect Questions

Click here to view a video that explains indirect questions.

Questions can also be direct or indirect. Direct questions go straight to the point and their intent is obvious. "Are you the legal owner of the contract?" or "How old are you?" and "How much are you willing to spend?" are direct questions. The problem with them is obvious. They can be off-putting and embarrassing, but their bigger problem is they bluntly expose your intent. They usually produce either incorrect information or none.

A better approach is using indirect questions. With indirect questions, the intent is not so obvious. For example, to determine if someone s the legal owner of the contract: “What is your identity number?” or someone's age: "what is your date of birth?”

Indirect questions are softer and more comfortable for clients to answer. Information gained from them is usually honest and useful. Unfortunately, they may not leap to mind at just the moment you need them. So, plan some indirect questions in advance that will help you learn what you need to know about your clients. Also, raise your sensitivity to when you are asking direct and indirect questions. To help you get started, in the next activity, we will review two lists of sample questions, the first are direct, the second, indirect. Think about what makes them direct or indirect, how they would make you feel as a client, and if they would be useful to add to your own questioning repertoire.

Direct Questions

- "Why is that important?"

- "Did you make that decision?"

- "Do you really want to devalue your policy by taking those loans?"

Open and Indirect Questions

- "What do you feel will be most important in the decision?"

- "Where would you normally go for help with this type of project?"

- "What would you like the outcome of this conversation to be?"

- "What are your long term financial goals?"

- "What do you wish you could change?"

Biased / Leading Questions

If you are not careful and conscious of it, your questions may carry bias. Bias is when the wording or tone of your questions indicates what the correct answer should be. "You want me to increase your monthly contributions by R200 then, don't you?" and "You'd have to agree our product is better than our competitors, wouldn't you?"

Bias reduces your credibility and makes clients feel they are being manipulated. And depending on how asked, can be terribly insulting, especially if the client does not share your opinion. Raise your awareness to biased-sounding questions and don't let them creep into your discussions with clients. Here are some additional questions that you should not ask:

- "You wouldn't expect our competitor to recommend us, would you?"

- "You do care about the environment, don't you?"

- "You wouldn't want your children be left destitute, would you?

- "Saving money is important to you, isn't it?

The Importance of REALLY Listening

Are you Listening?

Esther Derby

This summer I had a rare-for-me experience. I had the opportunity to be THE CLIENT on a software development effort. I don’t mean buying a box of off-the-shelf software - you know, MS Office, Adobe Acrobat, Quicken - I mean a real development project for my Web site. I say opportunity because it never happened. Here's the way my conversation went when I contacted Web site specialist Cecil about the project.

“Hi, Cecil. I’d like to add a search capability to the articles page on my website,” I said. Cecil launched: “Well, the thing about search engines is that you have to register with each one and re-submit…”

“Ahem,” I interrupted. “Perhaps I wasn’t clear. I want people who come to my site to be able to search for articles on my site. I want site visitors to see a list of all the articles and be able to choose one to read—just like I have it now—but I also want them to be able to search for articles on a certain topic.” “Oh, well, then what you want is a self-administered database,” Cecil said. “I’m not sure I need a database. I’ve been doing fine uploading the articles with FTP. Plus, there’s only one author since it’s my site,” I said.

“I know I’ve seen other sites with search capabilities. Can't the visitor's search by topic without the whole database thing?” “You don’t understand,” Cecil said “We’re database gurus! We could convert your entire website to a database and then you could update the content….” “Thanks, Cecil. I’ll get back to you,” I said. I hung up the phone and sighed. It felt like Cecil hadn’t heard much of what I’d said, and wasn’t interested in what I needed or wanted. I was frustrated and discouraged. If you notice your clients seem frustrated when you are defining requirements (or worse, after you’ve delivered the system), consider making a shift in how you go about understanding client needs.

Open-ended and context free questions can help us explore what our clients want:

- What problem are you hoping to solve?

- What does a successful solution look like?

- How will the system be different from what you have now?

These questions may seem sort of wide open … and they are. These are good questions to ask at the beginning a project to understand where the client is coming from and where they want to go.

Manage Expectations

Chances are you won’t be able to deliver on everything your client wants. But when you have the information, you can begin to manage expectations. I had a client back in the early 80s who wanted to be able to talk to the computer and have it do what he asked it to do. Speech recognition was just coming out of the research labs, and there was no way I could deliver what he wanted with the resources available ($20,000 and a CICS mainframe system with dumb terminals!). But because I knew that was what he really wanted, we were about to have the conversation about whether that was achievable. He still wanted speech recognition, but because he had been listened to, he accepted that it wasn’t possible at that time.

Understand Priorities

What is most important to the client? If you can deliver the top 10 items on a 50- item list will the client be satisfied? If you get to the other 40, that’s great; if you don’t, you’ve still delivered value. But if you start with item 35 or 49, no matter how nifty it is, the client won’t be satisfied. By the way, I still don’t have a search capability on my website. I decided Cecil would lead me down a rabbit trail of nifty technology that was more than I needed and not what I wanted. Maybe he’ll read this article.

Rephrasing and Paraphrasing

As an active listening response, paraphrasing or rephrasing, clarifies understanding of what your client has said. Rephrasing is repeating to the speaker, in your own words, what you heard them say. This may sound basic and like a waste of time. After all, if they just said it, why repeat it? Rephrasing is one of the most powerful listening techniques available to you, and it is one of the easiest to learn. Simply think carefully about what you just heard, put it in your own words, and say it back to them in the form of a question.

Rephrasing shows the other person that you really understand their situation. It also gives the person a chance to repeat and expand upon their concern, which makes them feel better about it and gives you the chance to identify something you can do to make a difference. Keep in mind that a rephrase must be sincere. Artificially posing a rephrase does more damage than good. If you mindlessly repeated their sentence like a parrot, the client would probably get irritated.

Some good ways to begin rephrasing questions are the following:

- "As I understand it . . ."

- "Do you mean . . ."

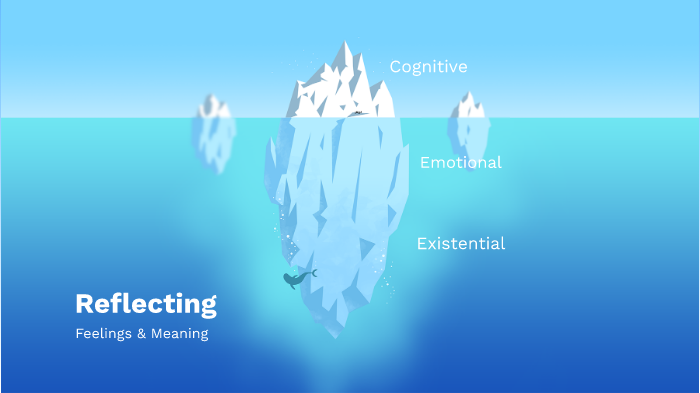

Reflecting Feelings

Clients also have feelings. They may phone in or visit your offices in a bad mood, or feeling angry, upset, or hurt. Something you may say might irritate them, sometimes company procedures are an irritation to them. Reflecting feelings feeds back the emotion communicated nonverbally by the client. When effective, reflecting feelings means you have grasped the implication of what the client just said. An example is when the client says he has had a busy week, and you say: "You must be glad it is Friday."

When your reflection on the implication is sincere and shows concern, it will be effective in communicating your interest. Use this listening technique with friends and family to gain a comfort level, then try it on clients. Before long, you'll be surprised to find yourself doing it naturally without even thinking about it.

Successful use of reflecting feelings entails focusing attention on the other person and repeating the feelings revealed. Avoid mentally processing how you think the person should be feeling, and use reflecting feelings sparingly. Usually reflecting feelings should be brief and stated in the second person:

- "You look relieved,"

- "You sound irritated."

- "You seem embarrassed."

- "You appear angry."

Verbal Expression

Use of Language

In writing and speaking we can use different types of language. In discussions at work, with clients, strangers, etc. there are unwritten rules that are followed. These unwritten rules are called "register use". Register use can help you communicate effectively. Incorrect register use can cause problems at work, cause people to ignore you, or, at best, send the wrong message. Of course, correct register use is very difficult for many learners of English. This feature focuses on different situations and the correct register used in the various situations. To begin with, let's look at some example conversations.

Formal: In the business environment it is customary to address your client in a formal register. If you see your client more frequently, the degree of your formality may decrease.

Informal: You use this type of language with people who are familiar to you. You may make good use of this register in verbal communications with clients, but you need to first find out whether your client would not be offended by your use of this register.

Slang: Slang is used by a specific group of people who understand the meaning of the words that are used. Different geographic communities may use words that are only understood in that community. For example, a group of friends may have made up their own words and “group language” which outsiders will not be able to understand. In an organisation, slang is company-specific jargon that is NOT formally accepted. Slang may be appropriate to use in interacting with your colleagues, but is not acceptable for use with clients.

Jargon: Jargon is language that is used by a specific group of people, which is normally not clear to others who are not part of this group. Jargon is useful when speaking to experts and members of the groups as it avoids long-winded explanations. But when dealing with a non-layperson, avoid jargon and use language that explains the concept to them clearly.

Verbal Mannerisms

Verbal mannerisms are the unconscious phrases we use such as “uhm”, “well”, “you know”. “er”. Sometimes we use these to “buy time, when we are thinking about an appropriate answer, “uhm” or to lead into a subject – “well…”. Sometimes we use them if we are nervous. Beware that they can interfere with meaning, give away a lot about your emotional state and be distracting for your listener.

Plain Language

Don’t use convoluted words. See! “Convoluted” is a word that shows off my vocabulary but could cause misunderstanding. To ensure that understanding happens first time around use plain language that is simple to understand. Let’s start again. Don’t use words that are difficult or complex when a plain word will do. This is not to say that you should not build your own vocabulary, to ensure that you understand people who do not use plain language.

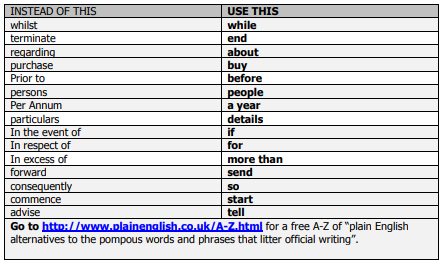

These are common words that we tend to use instead of their plain counterparts.