As demonstrated above, food quality cannot be defined as the absence of high microbial numbers alone, attention should be paid to those factors to which human beings respond, e.g.: changes in colour or texture, pH, concentrations of volatile sulphides, fatty acids, toxins and allergens.

Thus, the quality of meat is defined by many factors. These include:

Contamination by Micro-Organisms

Bacteria gain access to a carcass in the following ways:

Deep infection - the invasion of the musculature, via blood and lymph circulation. Such bacteria arise from either the intestinal tract which can infect the liver via the portal system or by the throat cut to cause the animal to bleed to death, allowing bacteria to enter the circulation system.

Contact or surface bacteriological contamination - the bacteriological load applied to the exposed surfaces of the carcass during the process of dressing and subsequent handling.

In general, the microflora on the meat will be that of the external surfaces of the animal, contaminating the meat by direct contact through the air, water, soil, manure and the hands and tools of the worker.

Three critical factors which influence the microbiological status of meat are:

- The microbiological status of the animal at slaughter

- The extent of transfer of micro-organisms to the meat during slaughtering and

- The temperature, time and other conditions of storage and distribution.

The main sources of contamination are:

- The slaughter man’s knife after the opening lines

- The hands and forearms of the slaughterman.

- Contact between freshly exposed surfaces of the carcass and dirty hides, fleece or slaughtering surfaces.

Chilling

In general, low-temperature preservation adds nothing to the quality of the final product. Its aim is only to slow down or arrest the micro-biological, biochemical and other effects that lead to spoilage. The quality and safety of the final product are determined by the initial quality of the muscle, hygiene standards during dressing and processing, temperatures throughout processing operations and finally the duration of and environmental conditions during the chilling and storage phase.

It is about the chilling stages that conflicting factors with regard to safety and quality often exist. Current regulatory stipulations for both local and export requirements stipulate a deep bone temperature of 7°C. Spoilage due to bone taint is unlikely to occur at this temperature. Low temperatures with high air velocities to obtain this temperature do however greatly increase the possibility of cold shortening, resulting in tough meat. Chilling procedures do not prevent the activity of spoilage organisms, which can grow at about 7°C however, temperatures below 2°C will delay the onset of slime formation. Control of the relative humidity in chill rooms, e.g.: reducing the amount of water activity, can reduce bacterial spoilage, but results in a loss of carcass weight and liability to spoilage by psychotropic bacteria and some moulds.

Residues

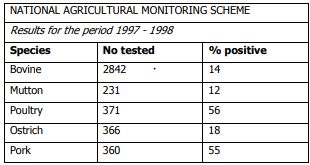

Agricultural chemicals and animal remedies are used extensively in SA to control pests and parasites in crops and to prevent and control diseases in livestock. These compounds may be taken up in the food chain and may therefore be in concentrations higher than the permitted maximum residue levels (MRL) safe for human consumption. The results below show the percentage of meat samples that tested positive for various residues during the 1997/1998 period:

Antibiotics

Organochlorines: 22 tests out of 963 were above the maximum residue limits.

Heavy metals: 3 tests exceeded the maximum residue levels.

National residue programmes conducted by Veterinary Public Health Authorities are currently used to verify the prevalence of residues and to provide health assurances to the local and international markets. The responsibilities in this regard should rest with or at least be shared by the producer.

Drug residues in food produced by animals may result in systemic toxicity, reproductive toxicity, genotoxicity, carcinogenicity, immunotoxicity, antimicrobial or pharmacological -effects following consumption in man. These effects may be acute or chronic in nature. An effective residue monitoring programme is essential for the control of residues in meat. Laboratory analyses are also used to provide information on both individual cases and screening tests to detect the presence of residues.

Click here to view a video that explains how much antibiotics are used in your meat.