Skimming and Scanning

Skimming involves searching for the main ideas by reading the first and last paragraphs, noting other organizational cues, such as summaries, used by the author.

In order to skim:

- Formulate questions before you begin e.g. what is this all about? Does this article deal with the subject I am researching?

- Read FAST bearing in mind your question(s).

- Do NOT read every word.

- Look at the opening paragraph of each chapter or section.

- Read the first sentence in each paragraph.

- Try to catch key phrases.

Scanning involves running your eyes down the page looking for specific facts or key words and phrases.

Think about what FORM the information will take: Is it a number? Is the word in capitals? How does it start?

- VISUALISE what the word or number looks like

- Use numerical order

- Do NOT read every word/number

- Read FAST and when you find the information you want then you slow down and examine it closely

Skimming and scanning are particularly valuable techniques for studying scientific textbooks. Science writers pack many facts and details closely together, and learners react by shifting their reading speeds to the lowest gear and crawling through the material. Notwithstanding the fact that science textbooks are usually well-organized, with main points and sub-topics clearly delineated, the typical learner ignores these clues and plods through the chapter word-by-word, trying to cram it all in. It is precisely these characteristics, organization and densities of facts per page that make it so vital that you employ skimming scanning techniques. To successfully master science test, you must understand thoroughly the major ideas and concepts presented. Without such a conceptual framework, you will find yourself faced with the impossible task of trying to cram hundreds of isolated facts into your memory.

Thus, a preliminary skimming for the main ideas by using the author’s organization cues (Topic headings, italics, summaries, etc.) is a vital preliminary step to more intensive reading and maximum retention. It will provide a logical framework in which to fit the details. Similarly, scanning skills are valuable for several purposes in studying science. First, they are an aid in locating new terms, which are introduced in the chapter. Unless you understand the new terms, it is impossible to follow the author’s reasoning without dictionary or glossary.

Thus, a preliminary scanning of the chapters will alert you to the new terms and concepts and their sequence. When you locate a new term, try to find its definition. If you are not able to figure out the meaning, then look it up in the glossary or dictionary. (Note: usually new terms are defined as they are introduced in science texts. If your text does not have a glossary, it is a good idea to keep a glossary of your own in the front page of the book. Record the terms and their definition or the page number where the definition is located. This is an excellent aid to refer to when you are reviewing for an examination, as it provides a convenient outline of the course). Secondly, scanning is useful in locating statements, definitions, formulas, etc. which you must remember completely and precisely. Scan to find the exact and complete statement of a chemical law, the formula of a particular compound in chemistry, or the stages of cell division. Also, scan the charts and figures, for they usually summarize in graphic form the major ideas and facts of the chapter. If you practice these skimming and scanning techniques prior to reading a science chapter, you will find that not only will your intensive reading take much less time, but that your retention of the important course details will greatly improve.

Concentrating and Reading

Learners often complain that they read but cannot remember what they have read. The reason for this is probably that they did not adapt their STYLE of reading to suit the type of text and purpose for reading. Make sure you stay alert whilst reading. Hold a soft pencil (2B) and MARK your textbook. This involves UNDERLINING key words and phrases. It is best to read a paragraph first and then underline when you read it again.

Marking a textbook may involve the following: x Writing summary words or phrases in the margin.

- Circling words for which you don’t know the meaning

- Marking definitions

- Numbering lists of ideas, cases, reasons, and so forth x Placing asterisks next to important passages

- Putting question marks next to confusing passages

- Marking notes to yourself like “check” “re-read”, or “good test item”

- Drawing arrows to show relationships

- Drawing summary charts or diagrams

Develop Your Own Codes. Here are Some Ideas:

Symbol Meaning

e.g. – example

def – definition

* – important message

T – good test question ?? – confusing

C – check later

RR – re-read

sum – summary statement

What Counts as Reading?

Reading is something we do with books and other print materials, certainly, but we also read things like the sky when we want to know what the weather is doing, someone’s expression or body language when we want to know what someone is thinking or feeling, or an unpredictable situation so we’ll know what the best course of action is. As well as reading to gather information, “reading” can mean such diverse things as interpreting, analysing, or attempting to make predictions.

What Counts as a Text?

When we think of a text, we may think of words in print, but a text can be anything from a road map to a movie. Some have expanded the meaning of “text” to include anything that can be read, interpreted or analysed. So, a painting can be a text to interpret for some meaning it holds, and a mall can be a text to be analysed to find out how modern teenagers behave in their free time.

How do Readers Read?

Those who study the way readers read have come up with some different theories about how readers make meaning from the texts they read. Being aware of how readers read is important so that you can become a more critical reader. In fact, you may discover that you are already a critical reader.

x The Reading Equation

x Cognitive Reading Theory

The Reading Equation

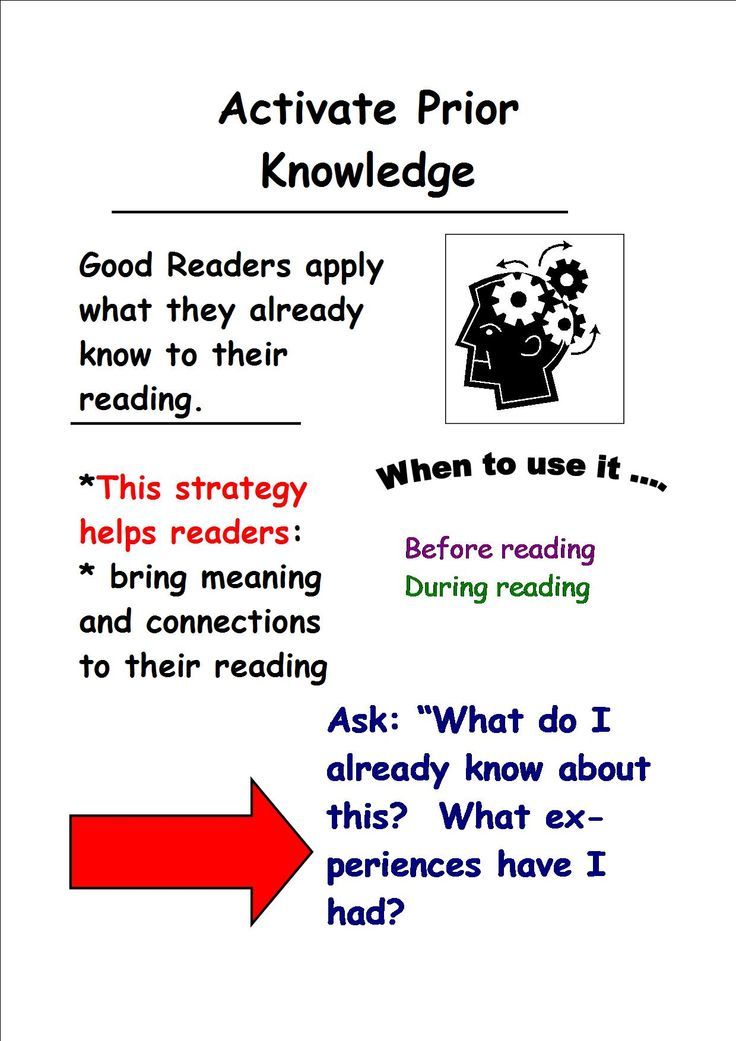

Prior Knowledge + Predictions = Comprehension

When we read, we don’t decipher every word on the page for its individual meaning. We process text in chunks, and we also employ other “tricks” to help us make meaning out of so many individual words in a text we are reading. First, we bring prior knowledge to everything we read, whether we are aware of it or not. Titles of texts, authors’ names, and the topic of the piece all trigger prior knowledge in us. The more prior knowledge we have, the better prepared we are to make meaning of the text. With prior knowledge we make predictions, or guesses about how what we are reading relates to our prior experience. We also make predictions about what meaning the text will convey.

- Tapping into Prior Knowledge

- Making Predictions

- How Reaching Comprehension Make Us Better Writers

Tapping Into Prior Knowledge

It’s important to tap into your prior knowledge of subject before you read about it. Writing an entry in your writer’s notebook may be a good way to access this prior knowledge. Discussing the subject with classmates before you read is also a good idea. Tapping into prior knowledge will allow you to approach a piece of writing with more ways to create comprehension than if you start reading “cold.”

Making predictions Whether you realize it or not, you are always making guesses about what you will encounter next in a text. Making predictions about where a text is headed is an important part of the comprehension equation. It’s all right to make wrong guesses about what a text will do – wrong guesses are just as much a part of the meaning-making process of reading as right guesses are.

How can Comprehension Make us Better Writers?

When you have successfully comprehended the text you are reading, you should take this comprehension one step further and try to apply it to your writing process. Good writers know that readers have to work to make meaning of texts, so they will try to make the reader’s journey through the text as effortless as possible. As a writer you can help readers tap into prior knowledge by clearly outlining your intent in the introduction of your paper and making use of your own personal experience. You can help readers make accurate guesses by employing clear organization and using clear transitions in your paper.

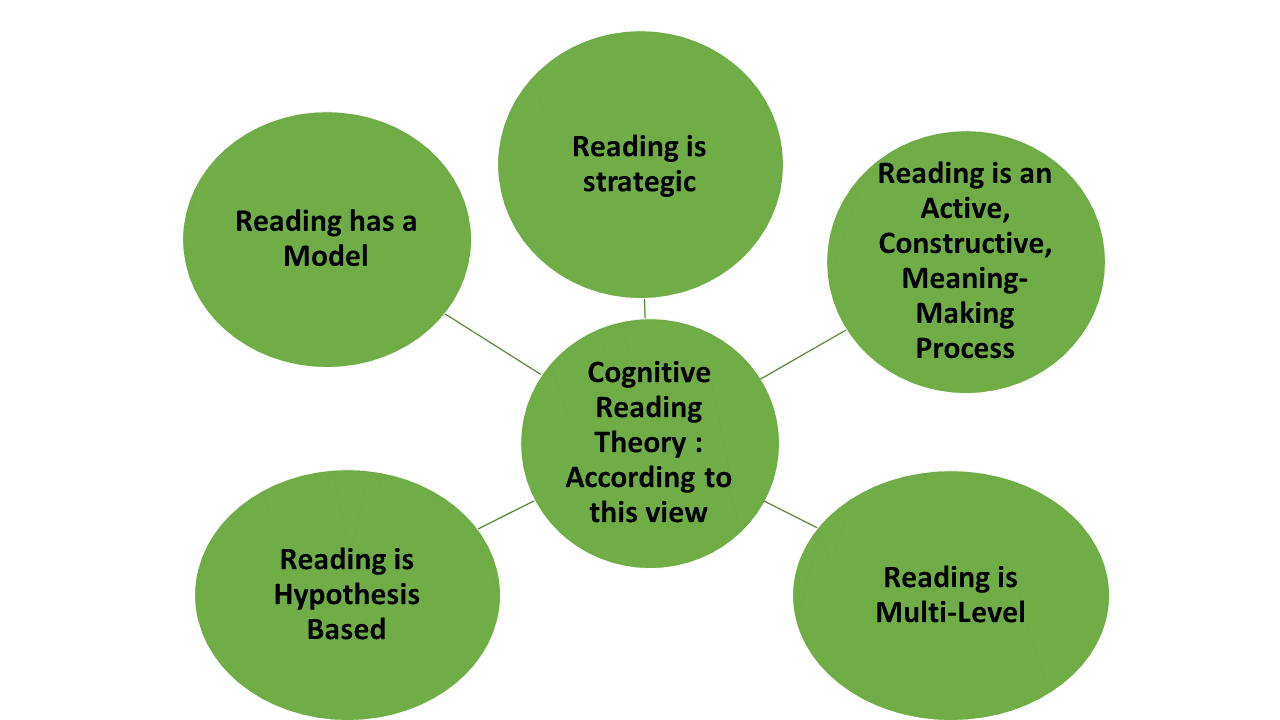

Cognitive Reading Theory

When you read, you may think you are decoding a message that a writer has encoded into a text. Error in reading comprehension, in this model, would occur if you as a reader were not decoding the message correctly, or if the writer was not encoding the message accurately or clearly. The writer, however, would have the responsibility of getting the message into the text, and the reader would assume a passive role.

According to this view:

- Reading has a Model

- Reading is an Active, Constructive, Meaning-Making Process

- Reading is Multi-Level

- Reading is Hypothesis Based

- Reading is strategic

Reading Has a Model

Let’s look at a more recent and widely accepted model of reading that is based on cognitive psychology and schema theory. In this model, the reader is an active participant who has an important interpretive function in the reading process. In other words, in the cognitive model you as a reader are more than a passive participant who receives information while an active text makes itself and its meanings known to you. Actually, the act of reading is a push and pull between reader and text. As a reader, you actively make, or construct, meaning; what you bring to the text is at least as important as the text itself.

Reading is an Active, Constructive, Meaning-Making Process

Readers construct a meaning they can create from a text, so that “what a text means” can differ from reader to reader. Readers construct meaning based not only on the visual cues in the text (the words and format of the page itself) but also based on non-visual information such as all the knowledge readers already have in their heads about the world, their experience with reading as an activity, and, especially, what they know about reading different kinds of writing. This kind of nonvisual information that readers bring with them before they even encounter the text is far more potent than the actual words on the page.

Reading is Multi-Level

When we read a text, we pick up visual cues based on font size and clarity, the presence or absence of “pictures,” spelling, syntax, discourse cues, and topic. In other words, we integrate data from a text including its smallest and most discrete features as well as its largest, most abstract features. Usually, we don’t even know we’re integrating data from all these levels. In addition, data from the text is being integrated with what we already know from our experience in the world about all fonts, pictures, spelling, syntax, discourse, and the topic more generally. No wonder reading is so complex!

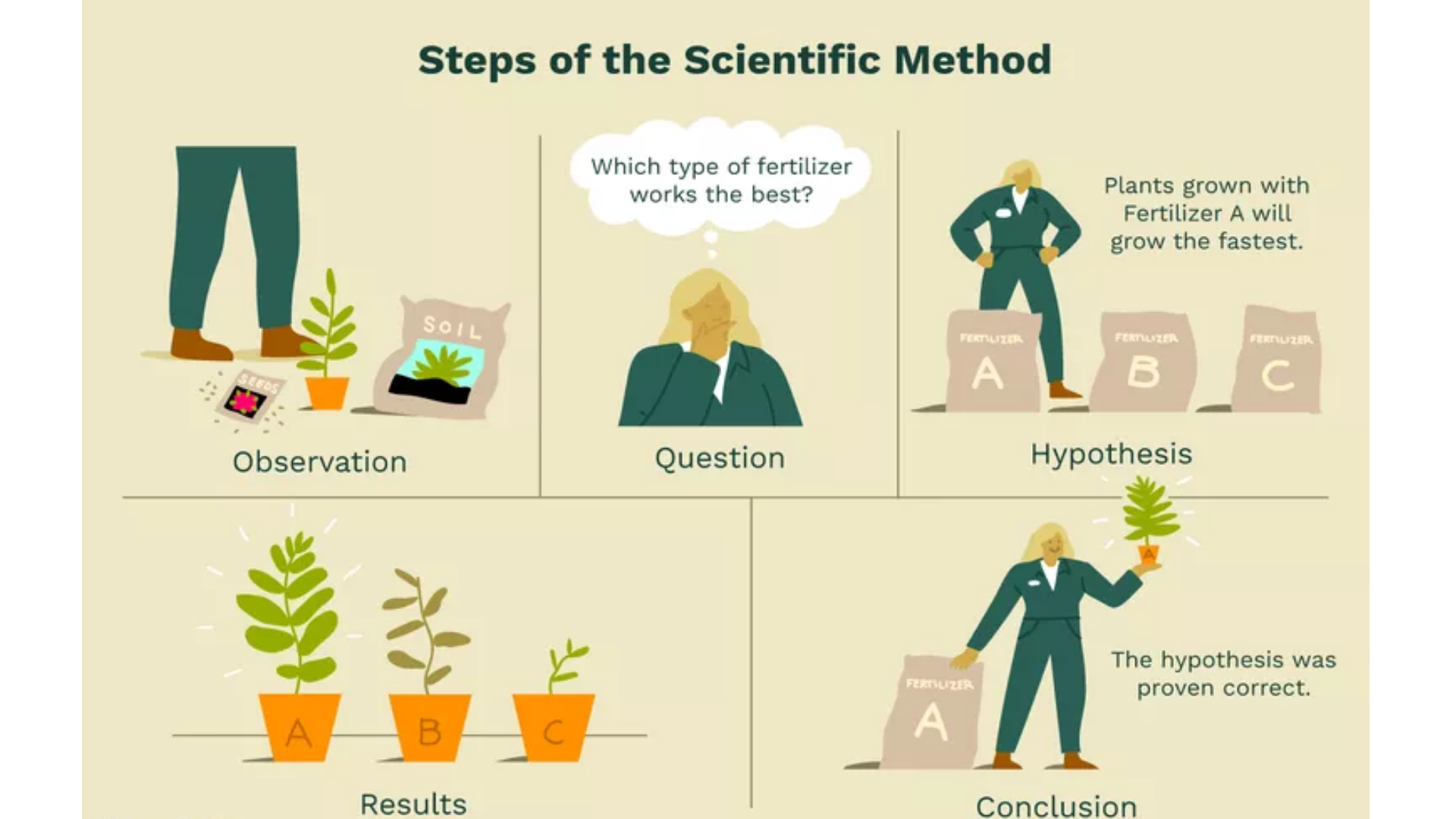

Reading is Hypothesis Based

In yet another layer of complexity, readers also create for themselves an idea of what the text is about before they read it. In reading, prediction is much more important than decoding. In fact, if we had to read each letter and word, we couldn’t possibly remember the letters and words long enough to put them all together to make sense of a sentence. And reading larger chunks than sentences would be absolutely impossible with our limited short-term memories.

So, instead of looking at each word and figuring out what it “means,” readers rely on all their language and discourse knowledge to predict what a text is about. Then we sample the text to confirm, revise, or discard that hypothesis. More highly structured texts with topic sentences and lots of forecasting features are easier to hypothesize about; they’re also easier to learn information from. Less structured texts that allow lots of room for predictions (and revised and discarded hypotheses) give more room for creative meanings constructed by readers. Thus, we get office memos or textbooks or entertaining novels.

Reading is Strategic

We change our reading strategies (processes) depending on why we’re reading. If we are reading an instruction manual, we usually read one step at a time and then try to do whatever the instructions tell us. If we are reading a novel, we don’t tend to read for informative details. If we a reading a biology textbook, we read for understanding both of concepts and details (particularly if we expected to be tested over our comprehension of the material.) Our goals for reading will affect the way we read a text. Not only do we read for the intended message, but we also construct a meaning that is valuable in terms of our purpose for reading the text. Strategic reading also allows us to speed up or slow down, depending on our goals for reading (e.g. scanning newspaper headlines v. Carefully perusing a feature story).