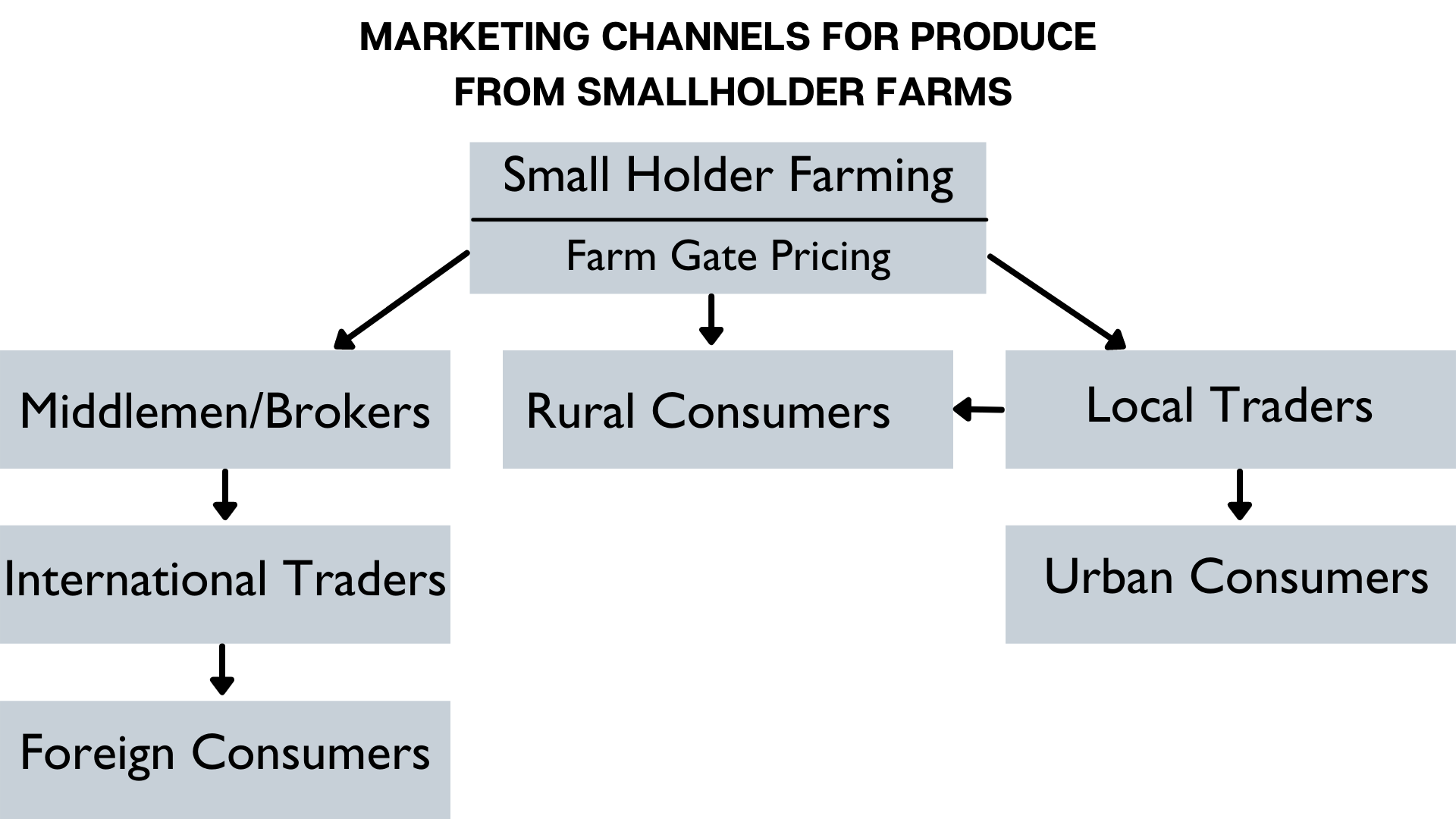

Marketing Channels For Produce From Smallholder Farms

The figure above illustrates the different paths that followed from produce harvested and sold by smallholder farmers until it reaches the consumer. Produce from smallholder farmers is sold to consumers and traders at the farm gate, usually through informal transactions where prices and terms of exchange are unofficially negotiated.

Click here to view a video that explains the fresh market food supply chain.

Smallholder farmers face difficulties in accessing markets and as a result, markets do not serve their interests. Technical and institutional constraints make it difficult for them to access commercial markets.

Good roads, transportation and communication links are prerequisites to market access. Proper post-harvest handling and storage contribute to ensuring quality maintenance for perishable agricultural products.

Smallholder farmers often rely on open-air storage and therefore are keen to sell produce almost immediately after harvesting, leading them to sell their product at a lower price.

Road infrastructure and transport availability have an influence on smallholder market participation, especially if they are located in rural areas. Inability to transport products in time may result in produce spillage and losses.

Selecting A Distribution Channel

For fresh produce, in particular, the distribution channel refers to the way and means by which the farm product is moved from the farm to the market. The mechanisms used vary depending on where the market is located in relation to the farm and on the requirements of the market. Commonly used distribution channels include wholesalers, distributors, sales representatives and retailers.

The preferred packaging required by the target market for fresh farm products is an important role in the choice of distribution channel. Fruit destined for the local wholesale market is usually packed either into jute or plastic pockets, usually in 10kg or 5kg units, or into 15kg cartons. Cartons are stacked onto wooden palletised and transported by road or rail. Pockets are either stacked directly into trucks or palletised for the journey to the market.

Informal traders who collect fruit directly from the packhouse in their own vehicles may load fruit lose into their vehicles.

Fruit for export is packed into specified cartons, most commonly 15kg, with dimensions that are configured for palletisation. Stacked pallets are either loaded onto vehicles or rail trucks, or into shipping containers at the packhouse.

We can now see that there are many different forms and ways in which fresh farm products leave the farm for their journey to the market. Some products are transported following a cold chain. In the case of lettuce, the harvested lettuce is transported from the field to a packing shed that is refrigerated. The lettuces are packed using specific packaging, under refrigeration, stored in cold rooms and transported to the retailer in refrigerated trucks by road.

The farmer or packhouse decide which markets to serve, ensure that the packaging form is aligned with market requirements and is cost-effectively utilised. The farmer or packhouse then decide, alone or in consultation with the market agent or exporting company, how the product will be transported to the market or port terminal.

In the case of exports, decisions also have to be taken about which logistics service provider and shipping company to use. The cost of transporting the product to the markets of choice in good condition depends on the efficiency and capability of the agencies used.

Deciding on which logistics service provider in the distribution channel to use depends on:

- The ability to provide the desired service

- The reputation of the service

- The cost of the service

Transport Modes

The choice of distribution model has cost implications and therefore has an influence on the distribution budget.

The farmer or packhouse has to decide which mode of transport to use to convey the packed product to the market. Cost is the main consideration in making this decision, but not the only one. Other factors include the practicality, reliability, reputation, and general standard of service delivery associated with the different modes of transport and transport contractors.

Export fruit has to be transported from the packhouse to a local depot or port, from there to an overseas port, and from the overseas port to an overseas depot or market. Different modes of transport are in most cases used for the different sectors of this journey.

The inland part of the transport leg can be completed by road or rail, or a combination of the two, depending largely on where the packhouse is located. Almost all cooperative pack houses and some independently run pack houses are located on rail sidings, in which case rail transport is the logical option. However, in many instances, poor rail services, as a result of unreliable capacity, time delays and uncompetitive tariffs, have resulted in road transport being more attractive. Ultimately, market forces will determine what mode of transport is used.

Before the 1980s, a high proportion of farm products were transported from the interior of the country by rail. Today the situation is very different, with a much higher proportion being transported by road, simply as a result of competitive rates and service delivery requirements driving producer decisions.

Sea freight accounts for virtually 100% of the transport mode used to convey farm products from South Africa to its various export markets. This is even the case with African markets other than those with borders close to South Africa.

On rare occasions, air freight is used for exports, but this is usually early in the season of a popular cultivar when a producer and his export agent decide to be the first on a poorly supplied market. Speciality crops that are placed into niche markets are often transported by air. An example of this is airfreighting of blueberries from South Africa to the UK. South African Blueberry exports occur in the months when blueberry is not harvested in Europe. The consumers are then willing to pay a “levy”’ on the produce. In some instances, market prices may, for a short period of time (days), justify the high cost of airfreight.

On arrival at overseas ports, the palletised farm product is conveyed most often by road transport to depots or directly to retailers in the case of supermarkets.

In the case of locally marketed fresh farm products, depending on the quantities of produce involved, the proximity of rail stations, the location and nature of the market to which the products are being sent, and the price quoted, either road or rail is used. Since relatively small volumes of product are sent by any single producer to any specific market, the road is the most commonly used transport mode.

Cooperative Marketing And Distribution

A cooperative is an organisation comprising a number of individual farmers as its members. A cooperative is formed to benefit from the economies of scale that their collective supply and marketing of products can achieve. This benefit can take various forms, most of which relate to the increased bargaining power that large volumes of products can achieve over smaller, fragmented volumes.

In terms of the marketing and distribution of fresh farm products, the cooperative has certain features that make it either attractive or unsuitable as a structure for individual growers to use.

The members of the cooperative usually comprise a number of individual farmers located within close proximity of distribution channels. As a group, the producers can offer the market-sustained volumes of a range of products or cultivars over an extended period.

The management of the cooperative negotiates with distribution service providers and evaluates market segment options on behalf of its members. Armed with the supply volumes of its members, the cooperative is able to negotiate from a position of strength and is usually able to conclude favourable contracts with export agents and importers.

One factor that can weaken the cooperative’s bargaining power is the potential variability of the quality of products emanating from its range of producers. All cooperatives have strict quality management systems in place, but quality variation is an inherent risk in a system where fresh farm products are supplied by many individual producers.

Distribution Channel Budget: Most costs associated with the production and packing of fresh farm products is fixed. Since there are various distribution options and logistics service providers from which to choose, costs can be saved in this area. It is therefore important to compare prices for the various stages of the distribution chain and use this information to create a distribution channel budget. The distribution budget serves as the financial expression of the distribution plan and in its formative stages is a useful tool for comparing different options.

Monitoring Distribution Channels: It is important for the farmer to enter into a contract or service-level agreement with the chosen transport and logistics service provider. In this agreement, the required service delivery standards should be clearly described. The actual service delivery is measured and monitored against this agreement, and payments are made accordingly. To ensure ongoing compliance by the service provider, it is important to maintain short interval control so that service delivery problems can immediately be brought to the attention of the service provider and appropriate action taken.

Monitoring the productivity of Transport providers and Distributers: The most obvious way of measuring the efficiency of transport and distribution contractors involved in the fresh farm product supply chain relates to the final condition and quality of the product they have been responsible for conveying. Fresh farm products are by nature, perishable products with a limited shelf life. Once the product has been produced, harvested and packed, time and temperature become the crucial parameters determining its quality and condition during and after the transport and distribution process.