Food comes in infinite variety and food choices are a major component of all purchase decisions made by consumers. However, despite the research that has been conducted during the last twenty years, there is no singular commonly accepted model for explaining consumer behaviour and food evaluation.

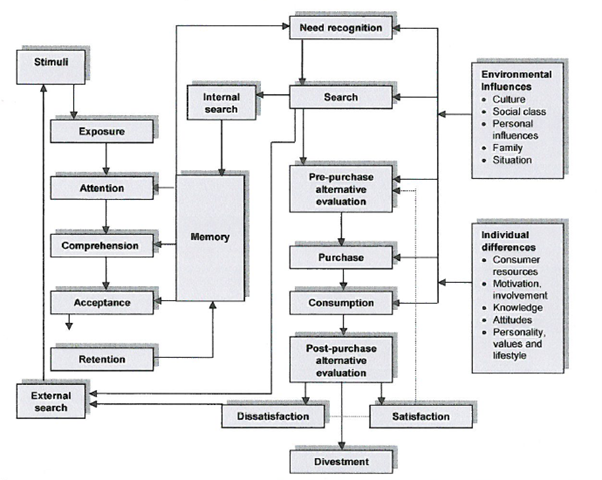

The Engel-Blackwell-Miniard Model Explaining How Consumers Make Buying Decisions

The model encompasses all types of need satisfying behaviour, including a wide range of influencing factors and different types of problem-solving processes. From the figure below, the model consists of four sections: decision process stages; information input; information processing; and variables influencing the decision process. The focus of the model is on the decision process stages problem recognition, search, pre-purchase alternative evaluation, purchase, consumption, post-purchase alternative evaluation, and divestment.

Information from marketing and non-marketing sources feeds into the information-processing section of the model. After passing through the memory, which serves as a filter, the information has its initial influence at the need recognition stage. Search for external information is activated if additional information is required or if the consumer experiences dissonance because of dissatisfaction with the chosen alternative. The information processing section of the model consists of the consumer’s exposure, attention, comprehension, acceptance and retention of incoming information. The last section of the model consists of individual and environmental influences that affect all stages of the decision process.

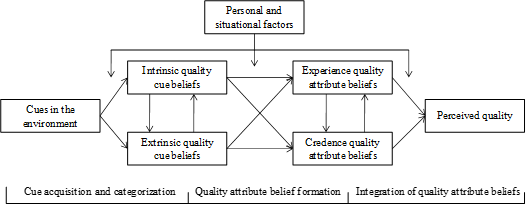

Steenkamp Model for Consumer Food Choices

One of the most pervasive models concerning consumer behaviour towards food is the model proposed by Steenkamp (1997). His model also distinguishes between the consumers’ decision-making process with respect to foods, and the factors influencing this decision process.

In the decision process, ‘borrowed’ from the EBM model, four stages are identified: need recognition, search for information, evaluation of alternatives, and choice. Three groups of factors influencing the decision process are recognized: properties of the food, factors related to the consumer, and environmental factors.

Comparing the Steenkamp model with the EBM model, the most noticeable difference is the lack of an explicit treatment of the information processing perspective. In the Steenkamp model, the marketing stimuli are spread across the three groups of factors and are considered to influence consumer behaviour in the same way as culture or the socio-demographic characteristics of the individual. However, even Steenkamp (1997) acknowledges that the boundaries between the three groups of influencing factors are fuzzy and that mutual influences may occur.

In the Steenkamp model, a special emphasis is given to the food product, as one of the major influences on food choice. The food product affects the decision process mainly through physiological effects and sensory perception. This focus is probably related to the fact that, in general, food products are commodities, sold unbranded or unlabelled and with poor or inexistent communication around them. Consequently, the models and the research dealing with consumer choice and behaviour relating to food are, mostly, concerned with the influence of physical and sensory properties of the products and of price. In summary, it can be said that the Steenkamp model is a simpler version of the EBM model, which emphasises aspects that are particular to food products.

The Verbeke Model

More recently, Verbeke (2000) proposed a four-component conceptual framework for analysing consumer decision-making toward fresh meat. As in the Steenkamp model, a four-stage model of the decision-making process forms the point of departure of his framework.

However, in addition to the Steenkamp model, this model is linked first with a ‘hierarchy of effects’ model and then, as in the EBM model, concepts related to information-processing are implemented. Finally, the Steenkamp (1997) classification of factors or variables that potentially influence consumer decision-making is also adopted. According to Verbeke (2000), the ‘hierarchy of effects’ indicates the different mental stages that consumers go through when making buying decisions and responding to marketing or non-commercial messages. Verbeke (2000) argues that while it is generally agreed that a structure including a cognitive, affective and conative component holds, no clear-cut evidence about the sequence and interdependency of these hierarchical steps appears to be available.

The Role Of Emotional Affections In Consumer Choice

It should be noted that there has been some criticism, even in the food field, of the cognitive-rational approach to the study of consumer behaviour. It is argued that several researchers have suggested that the ‘traditional’ cognitive view should be complemented by considering consumers’ affections, such as the possible emotional responses to the perception and judgement of products and of consumption experiences.

It is suggested that an individual can act based on an emotional feeling that is without or with just a low level of cognitive activity. The reason for this is that positive emotions seem to affect consumer purchase behaviour positively.

It seems as if there is an accompanying cognitive component to any sensory experience, in that prior experience with the same or similar products lends symbolic, associative and rhetorical meaning to any sensory experience. Generally, the consumer keeps an open mind towards useful stimuli in the environment, as is presupposed in the information processing perspective. To support the cognitive, information-processing perspective on consumer behaviour it can be added that cognitions might be beliefs about food (e.g. about its health properties), attitudes toward food (e.g. an overall evaluation), and preferences for food (e.g. plans to purchase or consume). Attitudes can have an affective component and are not, necessarily, formed on completely rational grounds.

In conclusion, it can be argued that, in general, choice and consumption of a product are based on a cognitive decision-making process and take account of stimuli surrounding that choice and consumption. Experience, sensory perception, and emotion or affect are important influences but, at some point in the experience with the product, an evaluation based on some criteria (objective or not) is made by the consumers of that product. Depending on the product and on the situation, the complexity of the choice may vary but, usually, there is a problem-solving approach to choose, even if affect or less rational factors influence the way people solve that problem. Thus, it can be said that the EBM model encompasses a wide range of situations and influences on consumer behaviour and, consequently, it can supply a basis for the analysis of behaviour relating to food.

Choice and Purchase of Food

In the Steenkamp (1997) model, food choice is characterised as being in accordance with attitude theory, which posits that the product alternative for which consumers hold the most positive attitude will be the chosen product. However, he acknowledges that there are several factors that weaken the relation between attitude and choice in the context of foods. For example, pressures from the social environment, the degree of behavioural control, habit, and variety-seeking behaviour. In the EBM model, attitude is related to alternative evaluation and choice as an influencing factor.

In the EBM model, decision rules represent the strategies that consumers use to select from the choice alternatives. These rules may be stored in memory and retrieved when needed. Alternatively, they may be constructed to fit situational contingencies. Purchase consideration and choice is a comparative process in which competing brands or products are evaluated.

For Engel et al. (1995), decision rules vary considerably in their complexity. They may be very simple, for example, to repeat a previous purchase decision, or they can be quite complex, involving the consideration of multiple criteria. Another important distinction is between compensatory and non-compensatory decision rules. Non-compensatory decision rules do not permit product strengths to offset product weaknesses. In contrast, compensatory rules do allow product weaknesses to be compensated by product strengths. When the choice is habitual, and even when the choice is not habitual, consumers may employ simplistic decision rules. This is explained by the fact that consumers continually make trade-offs between the quality of their choice and the amount of time and effort necessary to reach a decision. In many cases, the consumer will follow decision rules that yield a satisfactory (as opposed to optimal) choice while minimizing their time and effort.

There seems to be a difference between foods that are selected after detailed cognitive processing, which involve the use of structured attitude and belief models, and those that are not. For the latter products, it is more likely that sensory properties may well form good predictors, although the mediating effect of usage context will still be important. Nevertheless, the authors argue that, now of purchase, the decision-making process is purely cognitive, and the sensory properties are those expected from previous memory, from direct claims on the package, inferred from the images and information, or indeed from handling the product itself. It is, therefore, appropriate to examine the role of sensory properties as just one element in the general attitudes and beliefs model. Moreover, at the point of purchase, expectations of the sensory properties may contribute to the perception of a product before consumption, and therefore impact the choice decision. Expectation can therefore mediate food selection behaviour.

As was mentioned in the previous section, the result of the evaluation process is a preference for a product. Preferences imply choice. To prefer a food is to choose it over another designated food (or other activity). In more affluent cultures, as availability and cost recede in importance, preference is more in line with use. Liking is a major cause of preference but not the only cause. As with the use/preference comparison, as certain constraints (in this case health and social factors) fall into the background, liking becomes equivalent to preferring.

Click here to learn more about the different consumer behaviour models.

Klik hier om meer oor die verbruikers aankope besluite modelle te leer.

Click here to view a video that explains the labelling process of food.

Click here to view a video on how the outbreak of the Corona Virus in 2020 impacted consumer behaviour and the fresh produce market in SA.