HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, has become one of the world’s most serious health and development challenges:

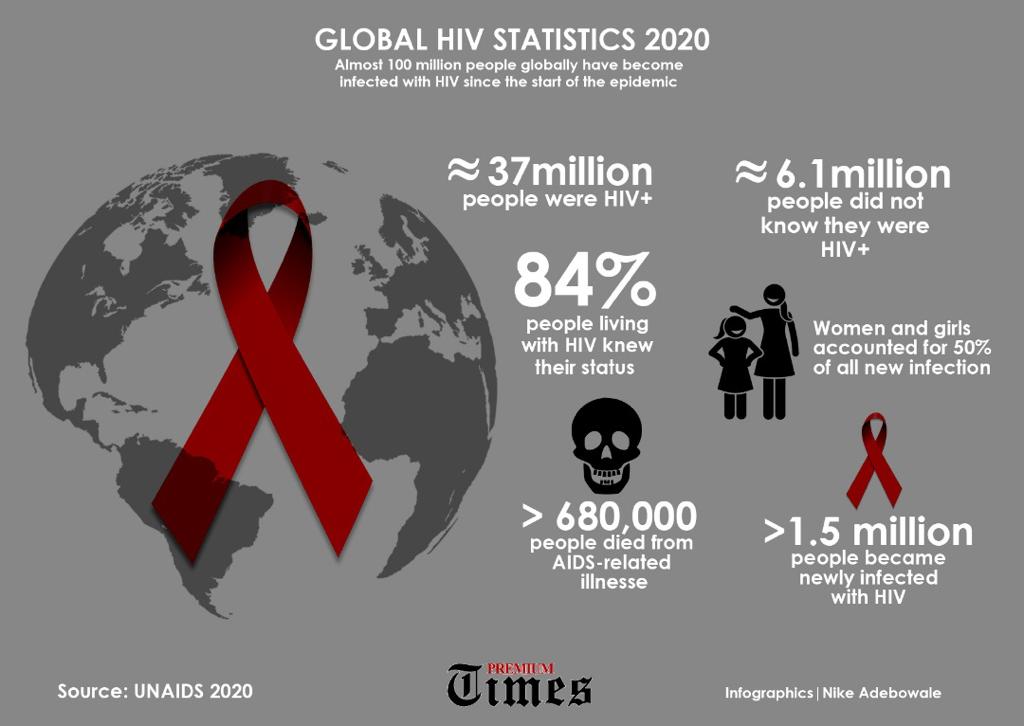

- 33.4 million are currently living with HIV/AIDS.

- More than 25 million people have died of AIDS worldwide since the first cases were reported in 1981.

- In 2008, 2 million people died from HIV/AIDS, and another 2.7 million were newly infected.

- While cases have been reported in all regions of the world, almost all those living with HIV (97%) reside in low- and middle-income countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa.

- According to the World Health Organization (WHO), most people living with HIV or at risk for HIV do not have access to prevention, care, and treatment, and there is still no cure.

- The HIV epidemic not only affects the health of individuals, but it also impacts households, communities, and the development and economic growth of nations. Many of the countries hardest hit by HIV also suffer from other infectious diseases, food insecurity, and other serious problems.

- Despite these challenges, there have been successes and promising signs. New global efforts have been mounted to address the epidemic, particularly in the last decade. Prevention has helped to reduce HIV prevalence rates in a small but growing number of countries and new HIV infections are believed to be on the decline. In addition, the number of people with HIV receiving treatment in resource-poor countries has increased 10-fold since 2002, reaching an estimated 4 million by 2008.

Stigma and discrimination

Despite such HIV-prevention programmes on the ground, employee involvement and participation in these programmes still posed a challenge because of the stigma and discrimination associated with HIV and other human rights issues. HIV-related stigma and discrimination have a significant impact on the willingness of employees to be openly involved and participate in HIV prevention interventions at the workplace. Fear of social isolation and ridicule from co-workers discourage them, not only from disclosing their HIV status but also from making full use of the services available to them.

Under these circumstances, HIV transmission among employees would continue unabated.

Similarly, HIV-prevention interventions at the workplace are effective only if people perceived their work environment as being supportive and protective of their human rights. Conversely, employees who suffer disrespect for their human rights, such as confidentiality issues, privacy and informed consent regarding disclosure, find it difficult to get involved and participate in HIV prevention interventions at the workplace. For example, staff members of ActionAid, Mozambique were reluctant to get involved and to participate in consulting the peer educators, fearing that the conversations would not be kept confidential. Similarly, the staff members shunned voluntary counselling and testing services, which were perceived as indicative of HIV-positive status.

Lack of management support

Lack of management support may take the form of severely limiting employees’ active involvement and participation in HIV prevention interventions at the workplace. Employees merely become passive recipients of information passed from the top down, as the following example shows. Management of the South African Department of Land Affairs limits employee involvement and participation in HIV prevention at the workplace only to passive activities such as dissemination of information on HIV by internal email, putting prevention messages into pay-slip envelopes and placing HIV updates in lifts. Employees are not actively involved in other awareness campaign activities such as condom promotion and distribution, voluntary counselling and testing for HIV, STI diagnosis and treatment and peer education training. Because employees were not actively involved, these interventions were likely to fail, leading to the continued spread of HIV among the employees. Lack of management support also manifests itself in the insufficient budgetary support for the HIV prevention programme at the workplace.

The Centre for Health Policy argues that some workplaces run HIV-prevention interventions at the workplace without a sufficient budget. As a cost-saving measure, companies prefer passive activities that neither take employees away from their core business nor require a large budget to run.

The policy further argues that: “Businesses don’t want to pay for [education about] AIDS…”. However, the International Labour Organisation argues keeping employees healthy by preventing HIV infection from spreading is essential for the viability of the business in the long run. The report cites a study carried out in Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, Mozambique and Zimbabwe which estimates that by 2020, the labour force in these countries will be an estimated 10 to 22 percent smaller than it would have been because of AIDS. Absenteeism due to HIV, coupled with the increased entry of young unskilled personnel into the labour market is likely to lower both the quantity and quality of productivity and production. The implication of the ILO’s report is that it is in the company’s interest to budget sufficiently to allow employees to get involved and participate in HIV prevention activities such as peer education training, VCT, STI diagnosis and treatment and condom distribution.

I felt the above arguments about the lack of management support for HIV prevention interventions at the workplace were very pertinent and relevant to my study. Such lack of budgetary support was likely to lead to low levels of employee involvement and participation in HIV-prevention interventions at the workplace, resulting in the limited success of the intervention. In this regard, I also sought to explore the quality of management support in my research.

However, some studies have shown that not every company was so concerned about maximizing profit to the extent of being unwilling to “pay for the education about HIV”, as claimed above. For example, AngloGold, the largest gold mining company in South Africa, sets aside a sufficient budget for hiring specialists to train peer educators among miners. These miners disseminate leaflets on HIV transmission modes and teach other miners as well as commercial sex workers about HIV. This latter example showed that there were indeed companies that appreciated the value of getting employees involved and participating in HIV prevention interventions at the workplace. However, as I argued at the outset of this section, there was evidence to show that there were some companies that set aside insufficient budgets for the programme, a situation that might prevent employees from getting involved and participating in HIV prevention interventions at the workplace. The failure of employees to get involved and participate in HIV prevention interventions at the workplace might in turn result in the continued spread of HIV among employees.

Lack of role-modelling by management

Failure by management to lead by example in terms of the uptake of services such as VCT and attending awareness sessions might create a negative attitude towards the whole HIV-prevention intervention at the workplace. The Centre for Health Policy argues that most HIV-prevention activities such as awareness campaigns, condom promotion and distribution tend to be directed towards unskilled and shop floor workers, and not professionals and managers. Peer educators are drawn mostly from lower-level employees and not from management. According to the Centre for Health Policy, the reasons for this lack of involvement and participation of management are that management believes HIV “doesn’t affect us” and “it affects them”.

The implications of the above arguments are that a climate of “us” and “them” may create discrimination and suspicion between workers and management.

Employees may therefore feel discouraged from getting involved and participating in HIV-prevention interventions at the workplace.

Lack of involvement of key stakeholders

The limited success of many interventions to the lack of involvement and participation of the key stakeholders in the implementation of the interventions. Stakeholders hold the power over the organisation and may exert either beneficial or harmful influence over it.

HIV-prevention interventions at the workplace, limiting or excluding employees from the planning and implementation of HIV-prevention interventions at the workplace might lead to the failure of these interventions. The exclusion of the employees from these programmes is also likely to cause them (the employees) to deliberately or unwittingly work at cross purposes toward the objectives of the interventions, either as a way of protest or because they do not understand what is expected of them. Whatever the case may be, such a lack of employee involvement and participation in HIV-prevention interventions at the workplace is likely to lead to programme failure and the continued spread of HIV among employees.

On the other hand, the involvement and participation of employees in the planning and implementation of HIV-prevention interventions at the workplace were likely to improve the chances of sustainability of these interventions. Employees were likely to assume ownership of and would be committed to, these interventions.

Karl’s (2000) and Phillips’ (2004) arguments about the importance of stakeholder involvement in development interventions appear to have important implications for my study. Their assertions imply that the level of success in the implementation of an HIV-prevention intervention at the workplace is correlated to the level, nature and type of employee involvement and participation in these interventions.

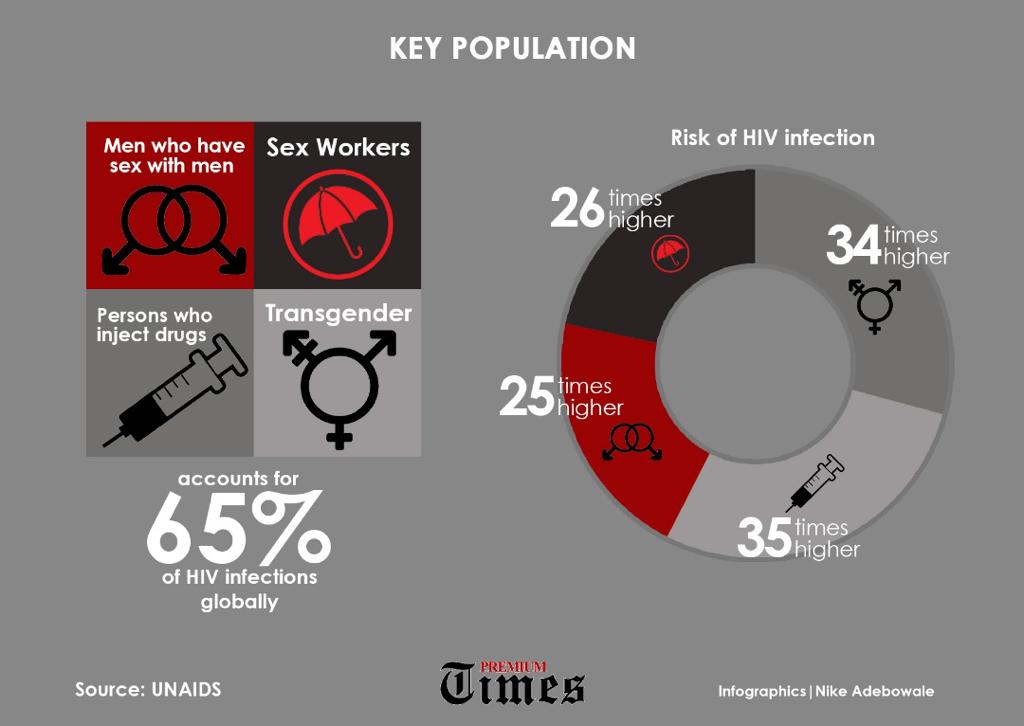

Socio-cultural and gender issues

Equally important are socio-cultural and gender factors that tend to influence an individual’s decision about one’s health-seeking behaviour. In this regard, the International Labour Organisation argues that many HIV-prevention interventions at the workplace focus predominantly on health issues, distribution of condoms and awareness sessions, and insufficiently on issues related to culture and gender. However, the context within which people live, their culture and gender have been shown to have a much higher impact on final behaviour such as getting involved and participating in HIV-prevention interventions at the workplace.

For many people, a decision is not an individual action, but a product of their cultural and societal environment Cultural diversity at the workplace also means divergence of perceptions about how HIV is transmitted, leading to different responses regarding involvement and participation in HIV-prevention interventions at the workplace. For example, employees whose social and cultural norms overtly or tacitly accept sexual risk-taking, or whose religious beliefs were against the use of condoms would find it challenging to get involved and participate in the promotion and distribution of condoms. Individual employees who come from a cultural background characterized by cultural barriers and gender norms that discourage open discussions of the behavioural risks of HIV may find it challenging to get involved and participate in HIV prevention interventions at the workplace.

Convincing people to change their behaviour is difficult if it is against their belief to do so, or if they believe that they are not personally at risk. By the same token, it would be difficult for employees to get involved and participate in condom promotion and distribution if they believe they are not personally at risk. Nor would they get involved and participate in any HIV-prevention activities if they believe that HIV is a result of witchcraft or is a form of punishment from God.

In a similar vein, gender inequality also works against the involvement and participation, particularly of female employees, in HIV prevention interventions at the workplace. In much of Africa, women and girls who carry condoms are regarded as ‘loose’ and are frowned upon by society.

As the United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) states, they are expected to passively submit to their partners’ demands for sex. The implications of these gender inequalities are that even when a woman is informed and has accurate knowledge about sex and HIV- prevention, the societal expectations that a ‘good’ woman should be naïve would make it difficult for her to get involved and participate actively in HIV-prevention interventions at the workplace. This gender inequality also manifests itself in the distribution of decision-making power between men and women in the workplace. Here, gender-linked cultural and economic inequalities mean that female employees have less decision-making power, responsibilities and access to company resources. Under such circumstances it is more likely for female employees to be sidelined in decision-making processes, making it difficult for them to get involved and participate in the planning, designing and implementation of HIV-prevention interventions at the workplace.

In addition, prevailing norms of masculinity expect men to be more knowledgeable and experienced about sex. Such norms prevent men from seeking information or admitting their lack of knowledge about sex or protection from contracting HIV. Men who get involved and participate in HIV prevention education often find themselves discriminated against by other men for failure to live up to masculine ideals. They are regarded as effeminate, weak or immature. As a result of this failure of male employees to get involved and participate in HIV-prevention interventions at the workplace, the spread of HIV transmission is likely to continue among employees.