Click here to view a video that explains the Expectancy Theory of Motivation

“Expectancy theory holds that people are motivated to behave in ways that produce desired combinations of expected outcomes” (Kreitner et al. 1999). As expectancy theory emphasizes cognitive ability to anticipate likely consequences of behaviour, perception plays a central role in it. According to Kreitner et al. (1999), the principle of hedonism is also embedded in expectancy theory as hedonistic people strive to maximize their pleasure and minimize their pain.

This theory can be used to predict behaviour in any situation where a choice between alternatives is to be made. It can for example be used to predict whether to quit or stay at a job, whether to exert substantial or minimal effort at a task and whether to study management, computer science, accounting or finance (Kreitner et al. 1999).

In this part we will focus on two expectancy theories of motivation: Vroom's expectancy theory and Porter and Lawler's expectancy theory. According to Kreitner et al. (1999), an understanding of these theories can help managers develop organisational policies and practices that enhance rather than inhibit employee motivation.

Victor Vroom’s mathematical model of expectancy theory has been summarized as follows: “The strength of a tendency to act in a certain way depends on the strength of an expectancy that the act will be followed by a given consequence (or outcome) and on the value or attractiveness of that consequence (or outcome) to the actor" (Kreitner et al. 1999: 216).

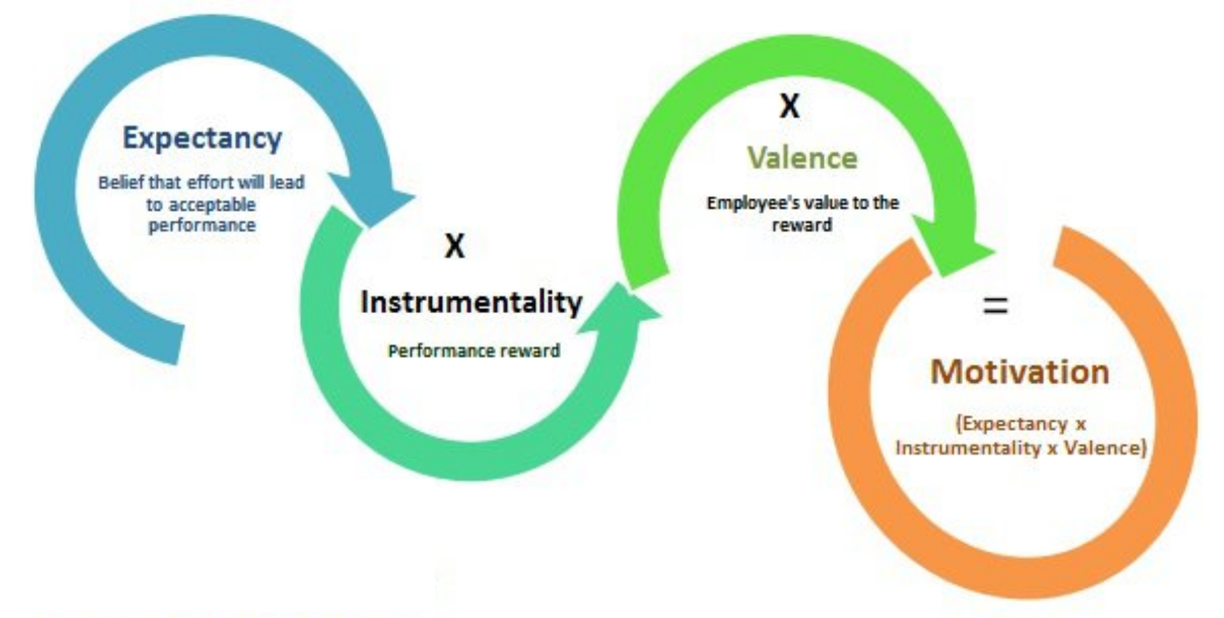

In Vroom’s view, motivation is about the decision of how much effort to exert in a specific task situation and the choice is based on a two-stage sequence of expectations (effort - performance and performance-outcome). Most behaviours are motivated as they are considered to be under the voluntary control of the person (Ivancevich et al. 1996). Motivation is affected by an individual's expectation that a certain level of effort will produce the intended performance goal, for example, if you do not believe increasing the amount of time you spend studying will significantly raise your grade on an exam, you probably will not study any harder than usual. “Motivation is also influenced by the employee’s perceived chances of getting various outcomes as a result of accomplishing his or her performance goal. Finally, individuals are motivated to the extent that they value the outcomes received” (Kreitner, 1999). Kreitner (1999) cited the following example: “Consider the motivation and behaviour of Hans Vermeulen. In 1993 Hans Vermeulen was expelled as a member of the Dutch Stock Exchange (AEX) by the disciplinary committee as a consequence of his misbehaviour in his trade activities. Many considered his punishment too light. Nevertheless, at the end of 1993, Hans Vermeulen became managing director at Leemhuis & Van Loon, a Dutch company active on the Dutch Stock Exchange. In 1995, Hans Vemeulen was again discredited for malversations, but nothing happened. In 1997, he was at last arrested for committing fraud and for laundering practices. Based on expectancy theory, we would expect Hans Vermeulen to continue his current behaviour because he values money highly and there are no major consequences for his questionable conduct."

A mathematical equation was used by Vroom to integrate these concepts into a predictive model of motivational force or strength. The key concepts however, within Vroom's model that are of importance to us, are first- and second-level outcomes, (Ivanceviech et al, 1996), instrumentality, valence (Kreitner, 1999:217) and expectancy.

First-level outcomes resulting from behaviour are, according to Ivancevich et al. (1996), those associated with doing the job itself and include productivity, absenteeism, turnover, and quality of productivity. The second-level outcomes are rewards and punishments that the first-level outcomes are likely to produce, such as merit pay-increase, group acceptance or rejection, promotion and termination.

Instrumentality refers to the perception by an individual that first-level outcomes are associated with second-level outcomes. It relates to a person’s belief that the attainment of a particular outcome will be instrumental in attaining one or more second-level outcomes (Ivancevich et al. 1996:168).

The concept of instrumentality can be seen in action by considering the "Winning Together" reward programme implemented at AlliedSignal's Engineered Materials division in Morristown, New Jersey as cited by Kreitner et al. (1999):

“It works something like an airline frequent flier program ... with employees at manufacturing locations awarded points for meeting specific goals on a quarterly basis. The employees can then accumulate points and cash them in for any of a range of specific non-cash rewards. According to Scott Pitasky, director/compensation for Engineered Materials, all manufacturing facilities establish metrics based on things such as safety, customer satisfaction and operational excellence, including capacity productivity and cost measures. Large scoreboards are posted indicating where the location stands relative to its goal. Under the "green light" program, progress toward meeting the goal is monitored continuously and summed up with a graph and traffic light symbol - red for underperformance, green for exceeding the goals." The "Winning Together" programme clearly makes performance instrumental for obtaining rewards.

Valence refers to the positive or negative value of a reward that people place on outcomes, for example, most employees have a positive valence for receiving additional money or recognition. In contrast, job stress and being laid off would likely be negatively valent for most individuals (Kreitner et al. 1999). Outcomes refer to different consequences that are contingent on performance, such as pay, promotions or recognition. The valence of an outcome depends on an individual's needs and can be measured for research purposes with scales ranging from a negative value to a positive value. Outcomes are positively valent when they are preferred and negatively valent when they are not preferred. When an individual is indifferent towards attaining or not attaining an outcome, it has a valence of zero (Ivancevich et al. 1996). For example, an individual's valence towards more recognition can be assessed on a scale ranging from -2 (very undesirable) to 0 (neutral) to +2 (very desirable) (Kreitner et al. 1999).

According to Vroom's terminology, an expectancy represents an individual's belief that a particular degree of effort will be followed by a particular level of performance. Kreitner et al. (1999) cites the following example:

“Suppose you do not know how to use a typewriter. No matter how much effort you exert, your perceived probability of typing 30 error-free words per minute would probably be zero. An expectancy of one suggests that performance is totally dependent on effort. If you decided to take a typing course as well as practice a couple of hours a day for a few weeks (high effort), you should be able to type 30 words per minute without any errors. In contrast, if you do not take a typing course and only practice an hour or two per week (low effort), there is a very low probability (say, a 20% chance) of being able to type 30 words per minute without any errors."

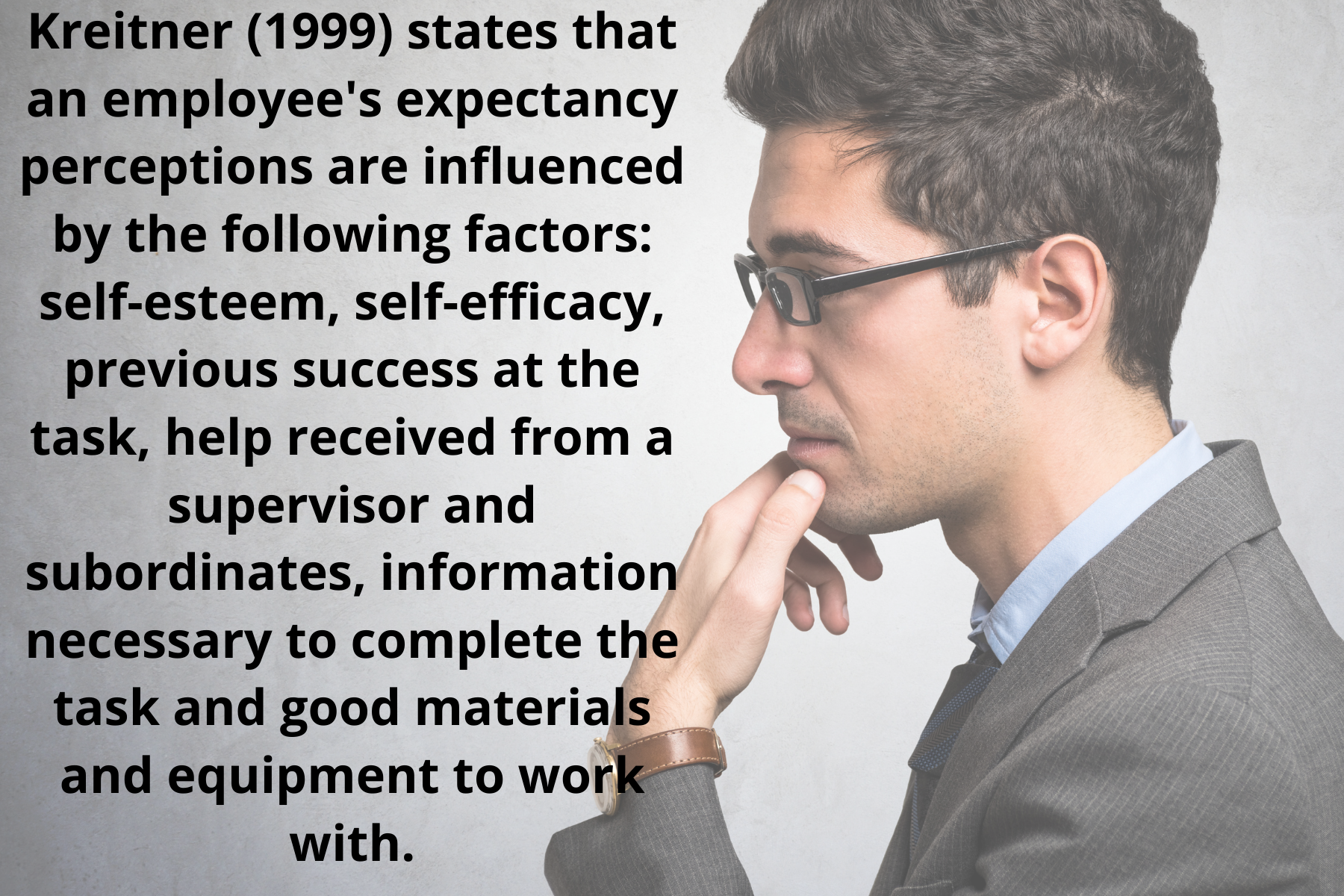

Kreitner (1999) states that an employee's expectancy perceptions are influenced by the following factors: self-esteem, self-efficacy, previous success at the task, help received from a supervisor and subordinates, information necessary to complete the task and good materials and equipment to work with.

Kreitner et al. (1999), used Vroom's expectancy model of motivation to analyse a performance problem described by Frederick W Smith, founder and chief executive officer of Federal Express Corporation: “...we were having a helluva problem keeping things running on time. The airplanes would come in and everything would get backed up. We tried every kind of control mechanism that you could think of, and none of them worked. Finally, it became obvious that the underlying problem was that it was in the interest of the employees at the cargo terminal-they were college kids, mostly-to run late, because it meant that they made more money. So what we did was give them all a minimum guarantee and say, "Look, if you get through before a certain time, just go home and you will have beaten the system." Well, it was unbelievable. I mean, in the space of about 45 days, the place was way ahead of schedule. And I don't even think it was a conscious thing on their part."

How did Federal Express get its student cargo handlers to switch from low effort to high effort? According to Vroom's model, the student workers originally exerted low effort because they were paid on the basis of time, not output. It was in their best interest to work slowly and accumulate as many hours as possible. By offering to let the student workers go home early if and when they completed their assigned duties, Federal Express prompted high effort. This new arrangement created two positively valued outcomes: guaranteed pay plus the opportunity to leave early. The motivation to exert high effort became greater than the motivation to exert low effort. Judging from the impressive results, the student workers had both high effort performance expectancies and positive performance-outcome instrumentalities. Moreover, the guaranteed pay and early departure opportunity evidently had strongly positive valences for the student workers.

Lyman Porter and Edward Lawler III Expectancy Model

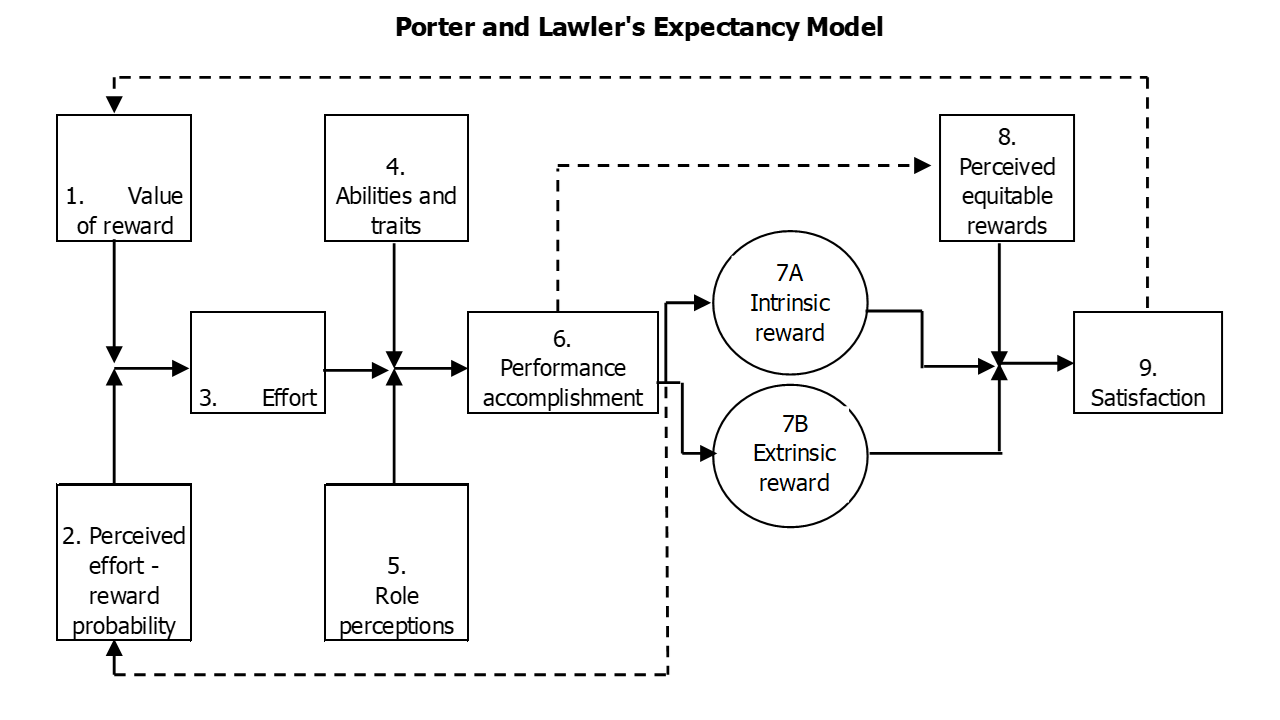

These two researchers developed an expectancy model of motivation that extended Vroom's work. This model attempted to (1) identify the source of people's valences and expectancies and (2) link effort with performance and job satisfaction (Kreitner, 1999:218-219).

Predictors of Effort: Effort is viewed as a function of the perceived value of a reward (the reward's valence) and the perceived effort-reward probability (an expectancy). More effort should be exhibited by employees when they believe they will receive valued rewards for task accomplishment (Kreitner et al. 1999).

Predictors of Performance: Performance is determined by more than effort and the relationship between effort and performance is moderated by an employee's abilities, traits and role perceptions. Employees with higher abilities attain higher performance for a given level of effort than employees with less ability. Effort also results in higher performance when employees clearly understand and are comfortable with their roles. This occurs because effort is channeled into the most important job activities or tasks (Kreitner et al. 1999).

Source: Kreitner, Kinicki and Buelens. 1999:219. Organisational Behaviour. McGraw-Hill. London.

Predictors of Satisfaction: Employees receive both intrinsic and extrinsic rewards for performance. Intrinsic rewards are those that an individual grant him/herself and consist of intangibles such as a sense of accomplishment and achievement. Extrinsic rewards are tangible outcomes such as pay and public recognition. Job satisfaction is determined by employees' perceptions of the equity of the rewards received. Employees are more satisfied when they feel equitably rewarded.

The Figure further shows that job satisfaction affects employees' subsequent valence of rewards. An employee’s future effort and reward probabilities are influenced by past experience with performance and rewards (Kreitner et al. 1999).

The accuracy of the expectancy theory in predicting employee behaviour has been the subject of numerous studies and direct tests have been generally supportive (Ivancevich et al. 1996: 167 - 168). Despite criticism of valence validity from certain quarters (Kreitner et al. 1999), the theory has important practical implications for individual managers and organisations as a whole. Kreitner et al. (1999) advise managers to enhance effort-performance expectancies by helping employees accomplish their performance goals by providing support and coaching and by increasing an employee’s self-efficacy.

(Kreitner et al. 1999). Managers importantly also need to influence employees' instrumentalities and to monitor valences for various rewards.

Kreitner et al. (1999) in relation to the previous paragraph, also raised the issue if monetary rewards should be an organisation’s primary method of reinforcing performance. Three issues need to be considered when deciding on the relative balance between monetary and non-monetary rewards. In the first instance, some research shows that workers value interesting work and recognition more than money, while, secondly, extrinsic rewards can lose their motivating properties over time and may then in turn undermine intrinsic motivation. Monetary rewards must lastly then be large enough to generate motivation and unfortunately, merit pay increases may not be large enough to create long-term motivation.

Kreitner et al. (1999) concluded that, there is no one best type of reward and need theories tell us that people are motivated by different rewards. “Managers should therefore focus on linking employee performance to valued rewards regardless of the type of reward used to enhance motivation” (Kreitner et al. 1999).

|

Managerial and Organizational Implications of Expectancy Theory |

|

|

IMPLICATIONS FOR MANAGERS |

IMPLICATIONS FOR ORGANIZATIONS |

|

Determine the outcomes employees' value. |

Reward people for desired performance and do not keep pay decisions secret. |

|

Identify good performance so that appropriate behaviours can be rewarded. |

Design challenging jobs. |

|

Make sure employees can achieve targeted performance levels. |

Tie some rewards to group accomplishments to build teamwork and encourage cooperation. |

|

Link desired outcomes to targeted levels of performance. |

Reward managers for creating, monitoring and maintaining expectancies, instrumentalities and outcomes that lead to high effort and goal attainment. |

|

Make sure changes in outcomes are large enough to motivate high effort. |

Monitor employee motivation through interviews or anonymous questionnaires. |

|

Monitor the reward system for inequities. |

Accommodate individual differences by building flexibility into the motivation programme. |

Source: Kreitner, Kinicki and Buelens. 1999:220. Organisational Behaviour. McGraw-Hill. London.

according to Kreitner et al. (1999), there are four prerequisites to linking performance and rewards: