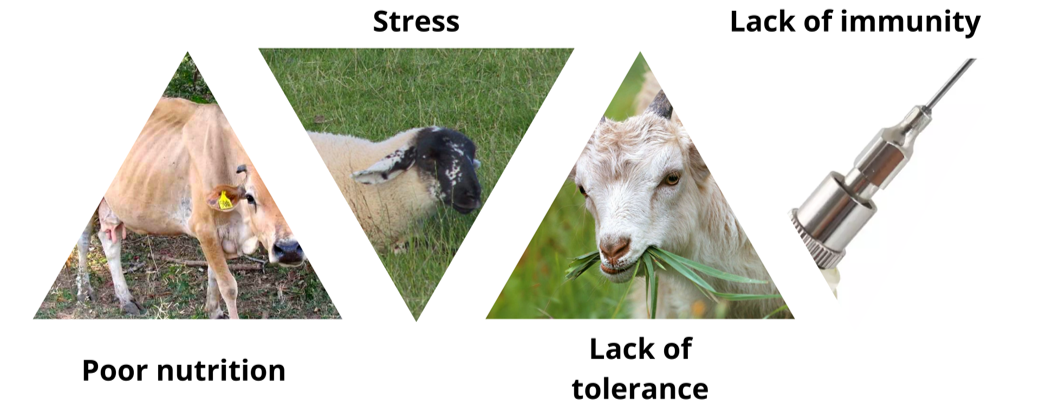

To maintain the health, vigour and productive ability of animals, a farmer needs to manage those factors which can challenge the health of the animal. There are four factors that need to be managed correctly to reduce the chance that diseases will occur.

Poor nutrition: A well-fed animal has a much better chance of fighting off disease and can convert nutrients in excess of maintenance requirements into products.

Stress: Any stress placed on an animal will make it more susceptible to disease (e.g. Pasteurella). Stress includes factors such as parturition, fatigue from walking or being transported long distances, poor housing, excessive cold (especially when combined with damp), excessive heat, high humidity, and dehydration.

Lack of tolerance: Animals in some areas are more tolerant to certain diseases because they have built up resistance to those factors through being exposed to them for many generations. For example, Goats are browsers, and thus less susceptible to picking up internal parasites from grazing infected pastures. Thus, if you then put a goat onto pastures he will pick up internal parasites more easily.

Lack of immunity: It is important to maintain an animal’s immunity levels. There are two ways, one is allowing the newborn to receive colostrum in the first few days after birth, and the other is through vaccination.

In general, long-term stress causes an increase in the production of cortisol by the adrenal cortex around the kidneys. Persistently elevated levels of cortisol in the blood cause the cells to develop a resistance to the function of insulin (which is to allow the entry of glucose into cells). Thus, glucose cannot enter cells and cannot be utilized by the cells to function normally, since glucose is the basic energy source for life. Elevated cortisol levels due to stress also cause a reduction in levels of FSH, LH, and growth hormones thus directly impairing reproduction and growth. Also, cortisol induces protein catabolism (breakdown) thus inducing muscle weakness.

All processes within the body rely on the supply of nutrients. These nutrients include proteins, energy, vitamins, minerals and water in the correct quantities and ratios. If any of these elements are not supplied in the correct quantities then malnutrition or starvation ensues. In some circumstances, where some nutrients are supplied in lieu (instead of) others the body may be able to manufacture the limiting nutrient. For example, an excess of protein can be converted into energy. However, when this occurs other organs and processes in the body can be negatively affected. For example: when an excess of protein and inefficient energy is supplied, the kidneys are placed under strain to excrete the excess amounts of urea. Some vitamins, minerals, amino acids and fatty acids are considered “essential” or ‘indispensable” and cannot be manufactured/synthesized by the body and must be ingested from an external source.

Malnutrition: Minerals

Although the animal body contains less than 5% in mass of mineral elements, some of these being present in minute traces only, their functional importance in the metabolism of the animal are considerable. Together with the vitamins, these elements are responsible for a major contribution to the health and production of the animal. It is no wonder then that the majority of unsoundness in animals is attributed to an inadequate supply or imbalance of one or more minerals or vitamins.

Mineral deficiency is generally attributed to seasonal climatic variations in the larger stock-raising areas where long, dry winters occur when veld grass leaches and becomes white, tough and unacceptable, and low in nutritional value. In addition, large areas are subject to periodic droughts when grazing becomes sparse and even unavailable. Dry winters chiefly apply to the summer-rainfall areas and in these areas lowered phosphorus levels act as a sensitive barometer of the nutritional status of the natural grazing. The deficiency can be so acute as to practically cause the disappearance of phosphorus after the first winter frosts, a factor that contributes to the unreliability of veld-pasture analyses. In the winter-rainfall areas, which includes the Western and South Western coastal strip, the dry period starts in late summer and is not as severe or as long as it is in the summer rainfall areas. However, a large variety of imbalances appear to be present, especially in trace elements such as copper, zinc, and magnesium manganese.

It is apparent, therefore, that for maximum productive performance, animals in all areas should have regular access to carefully balanced mineral compounds, in which special attention has been paid to phosphorus and salt as a base. The frame or skeletal development of an animal may ‘be considered the foundation upon which the rest of the body develops.

Calcium

A calcium deficiency is more likely to make its appearance in the prolonged presence of low calcium and high phosphorus. Although mild cases of Ca deficiency are not easily detected in cattle and sheep, a condition is known as “camped-under” is thought to be associated with a Ca deficiency. Cattle tend to place their hind limbs too far under the body, the result is that they stand on their heels and the hoof grows out long. In such circumstances bone fractures become common.

Phosphorus

However, unless animals have access to phosphatic supplements they lose condition and frequently develop a stiff gait and arched back. Many cases are evident where the hocks appear to be placed excessively far back in cattle. The end of the tail usually hangs between the hocks and the latter is frequently stained by faeces. In certain coastal areas where the interplay of certain trace elements may be more evident, calves show a peculiar stiffness in the forequarters prior to assuming a kneeling position. The condition is commonly referred to as stiff-sickness (“stywesiekte”) and is actually a form of osteomalacia or rickets. This condition may become progressively worse as the joints of animals become more painful and handicap them in their ability to cover distances for grazing. In the veld, mortality is often the sequel to bone-fracture disablement. “Stywesiekte” caused by a phosphorus deficiency must not be confused with three-day stiff-sickness, which has an insect vector.

Magnesium

Cases of magnesium deficiency have been described in young pigs and in calves as showing the weakness of the pasterns, particularly in the forelegs, causing backwards bowing of the legs, sickle hocks, arching of the back, hyper-irritability, muscle tremor, reluctance to stand, continual shifting of mass from limb to limb and eventually tetany and death.

Blood and Henderson (1971) describe three closely related syndromes associated with hypomagnesaemia:

- Hypomagnesaemia tetany of calves is thought to be a deficiency disease, as calves fed solely on whole milk or milk replacers can contract the condition in two to four months.

- Lactation tetany. Grass Staggers, or wheat pasture poisoning. This condition occurs mostly on lush green pastures, and

- Usually in cattle grazing on poor pastures and after a sudden cold spell in climate. Grashuis (1960) associates the onset of hypomagnesaemia with:

- An alkalosis due to excess fertilization of pasture with K and NH3.

- Low external temperatures.

- Digestive disturbances due to the formation of amines, e.g. histamine.

Source: Animal Nutrition, Concepts and Applications, PA Boyazoglu, Revised Edition

Sodium (Na) and Chlorine (CI)

Animals suffering from a salt deficiency manifest an intense craving for salt, loss of appetite haggard appearance, rough coat and lustress eyes. There is a rapid decline in milk flow and high producers may collapse and die. In advanced stages, cows may show neuromuscular abnormalities such as shivering.

A sudden excess of salt may result in toxicity, especially after animals have experienced a salt hunger, or insufficient water is available. However, when animals are accustomed to the conditions, large amounts of salt given with the object of controlling the intake of licks will prove relatively safe.

Potassium (K)

If animals were adequately fed, therefore, especially if sufficient roughage were available, there would normally be no deficiency of potassium.

The potassium, together with NaCI, has an important body function in controlling osmotic pressure and acid-base equilibrium which is responsible for the passage of nutrients into the body cells and also for water metabolism. All tissues contain intracellular potassium. Muscular tissue such as the heart is especially high in K content. A deficiency of potassium has been experimentally produced in dogs, pigs, calves and rats. Pathological findings according to King (1961) are necrosis of the myocardial fibres of the heart and of the renal tubular epithelium of the kidneys, and in dogs, in addition, paralysis had been observed. Cases are on record where administration of potassium salts affected improvement and cure of rheumatism.

Iron (Fe)

Iron forms an integral part of haemoglobin which in its turn act as the carrier of oxygen and the activator of several enzymes. The normal haemoglobin content of blood is 10 – 18 g per 100 ml.

Sulphur (S)

The body contains about 0.15% sulphur, chiefly present in keratin in the horns, claws, feathers, hair and wool.

The inclusion of 1 -2 % of flowers of sulphur in stock licks has for this reason been found to be a valuable antidote against “geilsiekte”.

Fluorine (F)

In the body, traces of fluorine are present chiefly in the skeletal material and teeth, where the very low concentration of 1 ppm total dry matter intake per day appears to be desirable. Although fluorine is present in all soft-body tissue and is excreted in urine and faeces, excessive intake over prolonged periods accumulates in the bones and teeth. The result is a mottling of the tooth enamel, which shows erosion and pitting, loss of appetite and emaciation, infertility and low production. A condition of typical osteoporosis develops in which bones show softening and knobbly lesions.