Case Study 1. (Kreitner et al. 1999:443)

“Imagine you are the general manager of the public transportation authority in a large city and one of your main duties is overseeing the city's bus system. During the past several years, you have noted with concern the increasing number and severity of bus accidents. In the face of mounting public and administrative pressure, it is clear that a workable accident-prevention programme must be enacted. Large pay rises for the bus drivers and other expensive options are impossible because of a tight city budget. Based on what you learned about motivation, what remedial action do you propose? (Please take a moment now to jot down some ideas.)

Since these facts have been drawn from a real-life field study, we can see what happened. Management tried to curb the accident rate with some typical programmes, including yearly safety awards, stiffer enforcement of a disciplinary code, complimentary coffee and doughnuts for drivers who had a day without an accident and a comprehensive training programme. Despite these remedial actions, the accident rate kept climbing. Finally, management agreed to a behaviour modification experiment that directly attacked unsafe driver behaviour.

One hundred of the city's 425 drivers were randomly divided into four experimental teams of 25 each. The remaining drivers served as a control group. During an 18-week period, the drivers received daily feedback on their safety performance on a chart posted in their lunchroom. An accident-free day was noted on the chart with a green dot, while a driver involved in an accident found a red dot posted next to his or her name. At two-week intervals, members of the team with the best competitive safety record received their choice of incentives averaging $5 in value (e.g. cash, free petrol, free bus passes). Teams that went an entire two-week period without an accident received double incentives.

Unlike previous interventions, the behaviour modification programme reduced the accident rate. Compared with the control group, the experimental group recorded a 25% lower accident rate. During an 18-week period following termination of the incentive programme, the experimental group's accident rate remained a respectable 16% better than the control groups. This indicated a positive, long-term effect. Moreover, the programme was cost effective. The incentives cost the organization $2,033.18, while it realized a savings of $9,416.25 in accident settlement expenses (a 1:4.6 cost/benefit ratio).

This particular programme worked, while other attempts failed because a specific behaviour (safe driving) was modified through systematic management of the drivers' work environment. If the intervention, involving posted feedback, team competition and rewards had been implemented in traditional piecemeal fashion, they probably would have failed to reduce the accident rate. These common techniques however produced favourable results when combined in a coordinated and systematic fashion (Kreitner et al. 1999). According to Kreitner et al. (1999), research in Finland has demonstrated that behaviour modification (B Mod) techniques reduced accidents by as much as 80%.

Behaviour modification, according to Kreitner et al. (1999:443), involve making specific behaviour occur more or less often by systematically managing its cues and consequences. E L Thorndike and B F Skinner were pioneering psychologists in the field of B Mod.

Edward L Thorndike observed during the early 1900s that a cat would behave randomly and wildly when placed in a small box with a secret trip lever that opened a door. Once the cat had accidentally tripped the lever and escaped, the cat would go straight to the lever when placed back in the box. Hence, Thorndike’s view that behaviour with favourable consequences tends to be repeated, while behaviour with unfavourable consequences tends to disappear (law of effect).

Skinner refined Thorndike's conclusion and his work became known as behaviourism because he dealt strictly with observable behaviour. As a behaviourist, Skinner believed it was pointless to explain behaviour in terms of unobservable inner states such as needs, drives, attitudes, or thought processes (Kreitner et al. 1999).He develop a sophisticated technology of behaviour control or operant conditioning. He for example taught pigeons how to pace figure-eights and how to bowl by reinforcing the underweight (and thus hungry) birds with food whenever they more closely approximated target behaviours. Skinner's work has significant implications for organisational behaviour because the vast majority of organisational behaviour fall into the operant category.

B Mod interventions in the workplace often involve techniques such as goal setting, feedback, and rewards; however, B Mod is unique in its adherence to Skinner's operant model of learning. Operant theorists assume it is more productive to deal with observable behaviour and its environmental determinants than with personality traits, perception, or inferred internal causes of behaviour such as needs or cognitions.

To understand the operant learning process, a working knowledge of behavioural contingencies is required. While some contingencies occur automatically, we set up others by linking our behavior with the behavior and that of others in an attempt to design an environment that will best serve our purposes. Setting up a contingency involves designating behaviors and assigning consequences to follow.

“We design contingencies for children fairly simply ("If you finish your homework, I'll let you watch television."), but influencing the behavior of people in the workforce is more difficult” (Kreitner et al. 1999).

The emphasis is on focusing on the behaviour and not on for instance the personality traits of an employee. The following case study as cited by Kreitner et al. (1999), serves as an example of the former and proposes how managers should describe job behaviour:

“THE WRONG WAY: Subjective appraisal of the person, rather than objective

information about performance.

Phil Oaks, the department manager, describes his subordinate, Joe Scott, as follows:

Well, Joe is just not easy to get along with. He's so disagreeable and negative all the time. He's very aggressive and disruptive. When he's unhappy he just sulks a lot, and he daydreams. He's also insubordinate and doesn't follow the rules. I don't know if he's immature, not intelligent or irrational. Overall, his motivation is very low. He lacks drive and is generally hostile. I suspect that there may be a home problem also.

THE RIGHT WAY: Objective information about observable performance behaviours, rather than subjective appraisal of the person.

In contrast, if Phil had training in pinpointing behaviours, he might describe Joe as follows: Well, whenever Joe is given some direction, he responds by immediately telling you why it can't be done. He frequently threatens other employees and has even been in one or two fights. He leaves his own work area to tell jokes to other workers. Sometimes he just sits in a corner or stares out the window for several minutes. He has violated several company rules such as smoking in a non-smoking zone, working without safety goggles, and parking in a fire lane. He can't seem to tell right-handed prints from left-handed prints. Also, he arrived late for work 10 times in the last month, and returned from his break late on 12 occasions.

Source: Performance descriptions excerpted, from C C Manz and H P Sims, Jr. Super Leadership: Leading Others to Lead Themselves (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1989), pp 66-67.

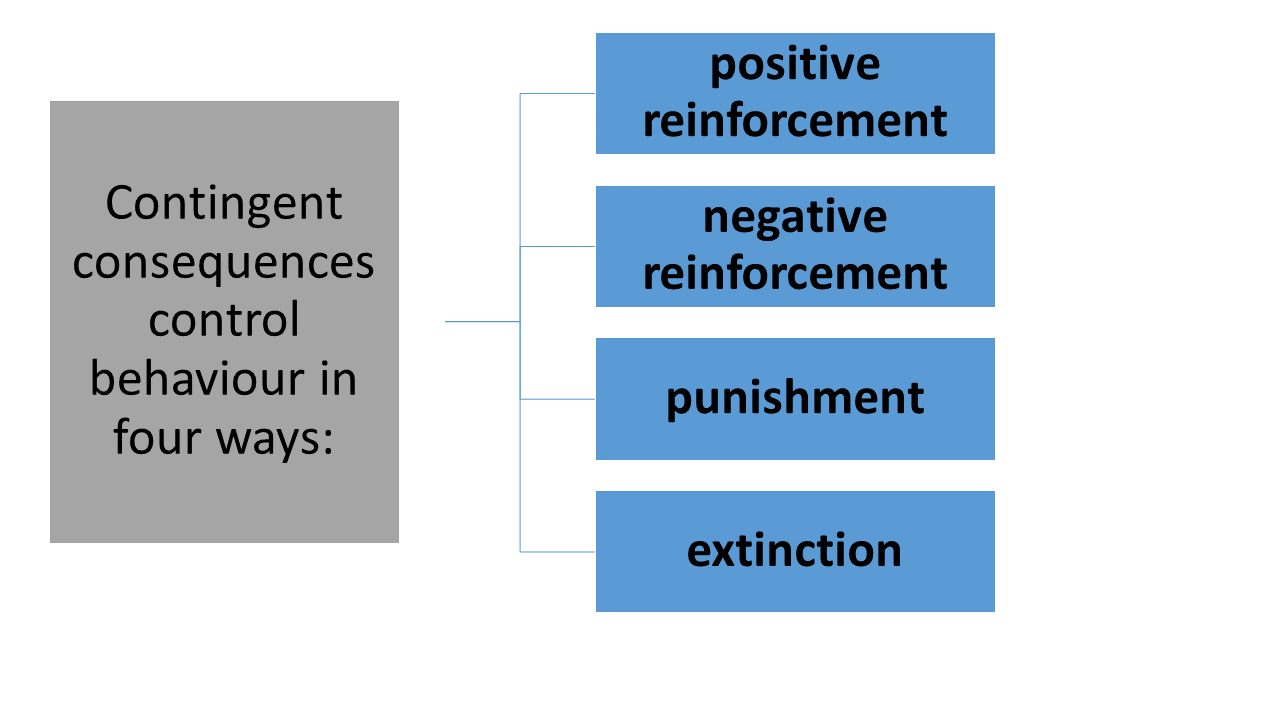

Contingent consequences control behaviour in four ways: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, punishment and extinction and these are managed systematically in B Mod programmes.

By contingently presenting something pleasing whenever a desired behaviour is displayed, that particular behaviour is strengthened through a process of positive reinforcement.

“Negative reinforcement is the process of strengthening a behaviour by contingently withdrawing something displeasing. For example, an army sergeant who stops yelling when a recruit jumps out of bed has negatively reinforced that particular behaviour.” (Kreitner et al. 1999).

Behaviour is weakened through the process of punishment. The latter consists of either the contingent presentation of something displeasing or the contingent withdrawal of something positive.

Extinction is the weakening of behaviour by ignoring it or making sure it is not reinforced.

Contingent Consequences in Behaviour Modification

|

Positive Reinforcement |

Punishment |

|

Behavioural outcome: |

Behavioural outcome: |

|

Target behaviour occurs more often. |

Target behaviour occurs less often. |

|

Punishment (Response Cost) |

Negative Reinforcement |

|

Behavioural outcome: |

Behavioural outcome: |

|

Target behaviour occurs less often. |

Target behaviour occurs more often. |

No contingent consequence: Extinction

Behavioural outcome: Target behaviour occurs less often.

Adapted from Kreitner, Kinicki and Buelens. 1999:447. Organisational Behaviour. McGraw-Hill. London.

Kreitner et al. (1999), proposes ten practical tips for shaping job behaviour that managers should find useful:

- Accommodate the process of behavioural change. Behaviours change in gradual stages, not in broad, sweeping motions.

- Define new behaviour patterns specifically. State what you wish to accomplish in explicit terms and in small amounts that can be easily grasped.

- Give individuals feedback on their performance. A once-a-year performance appraisal is not sufficient.

- Reinforce behaviour as quickly as possible.

- Use powerful reinforcement. To be effective, rewards must be important to the employee-not to the manager.

- Use a continuous reinforcement schedule. New behaviours should be reinforced every time they occur. This reinforcement should continue until these behaviours become habitual.

- Use a variable reinforcement schedule for maintenance. Even after behaviour has become habitual, it still needs to be rewarded, though not necessarily every time it occurs.

- Reward teamwork-not competition. Group goals and group rewards are one way to encourage cooperation in situations in which jobs and performance are interdependent.

- Make all rewards contingent on performance.

- Never take good performance for granted. Even superior performance, if left unrewarded, will eventually deteriorate.

Source: Adapted from A T Hollingsworth and D Tanquay Hoyer, How Supervisors Can Shape Behavior,Personnel Journal. May 1985, pp. 86, 88.