The readings in most learnership writing courses explore issues we live with daily. As a reader, you bring a wealth of relevant opinions, experiences, and language strategies with you to your work. So, while the authors you read in learnerships may describe common experience from abstract positions or use evidence that is detailed and complex, in many ways the strategies you use to analyse and evaluate writing are similar strategies you use to understand other complex situations: You think about what will probably happen, you listen carefully to what’s being offered, and you consider the offer and how it meets your needs. In the same way, you preview, read, and review the texts offered in this course.

The Process: Previewing

Before reading, you need a sense of your own purpose for reading. Are you looking for background information on a topic you know a little bit about already? Are you looking for specific details and facts that you can marshal in support of an argument? Are you trying to see how an author approaches her topic rhetorically? Knowing your own purpose in reading will help you focus your attention on relevant aspects of the text. Take a moment to reflect and clarify what your goal really is in the reading you’re about to do.

In addition, before reading, you can take steps to familiarize yourself with the background of the text, and gain a useful overview of its content and structure.

- Seek information about the context of the reading (the occasion – when and where it was published – and to whom it’s addressed),

- Its purpose (what the author is trying to establish, either by explaining, arguing, analysing, or narrating), and

- Its general content (what the overall subject matter is).

- Take a look for an abstract or an author’s or editor’s note that may precede the article itself, and read any background information that is available to you about the author, the occasion of the writing, and its intended audience.

Once you have an initial sense of the context, purpose, and content, glance through the text itself, looking at the title and any subtitles and noting general ideas that are tipped off by these cues. Continue flipping pages quickly and scanning paragraphs, getting the gist of what material the text covers and how that material is ordered. After looking over the text as a whole, read through the introductory paragraph or section, recognizing that many authors will provide an overview of their message as well as an explicit statement of their thesis or main point in the opening portion of the text. Taking the background information, the messages conveyed by the title, note or abstract, and the information from the opening paragraph or section into account, you should be able to proceed with a good hunch of the article’s direction.

Consider your Purpose

- Are you looking for information, main ideas, complete comprehension, or detailed analysis?

- How will you use this text?

- Get an overview of the context, purpose, and content of the reading.

- What does the title mean?

- What can you discover about the “when,” “where,” and “for whom” of the article?

- What does background or summary information provided by the author or editor predict the text will do?

- What chapter or unit does the text fit into?

- Scan the text.

- Does there seem to be a clear introduction and conclusion? Where?

- Are the body sections marked? What does each seem to be about? What claims does the author make at the beginnings and endings of sections?

- Are there keywords that are repeated or put in bold or italics?

- What kinds of development and detail do you notice? Does the text include statistics, tables, and pictures or is it primarily prose? Do names of authors or characters get repeated frequently?

Annotating a Text

Whatever your purposes are for reading a particular piece, you have three objectives to meet as your read: to identify the author’s most important points, to recognize how they fit together, and to note how you respond to them. In a sense, you do the same thing as a reader every day when you sort through directions, labels, advertisements, and other sources of written information.

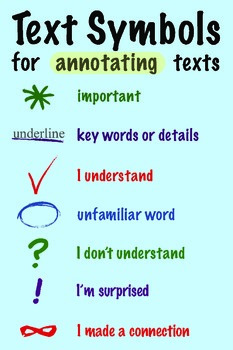

What’s different in a learnership is the complexity of the texts. Here you can’t depend on listening and reading habits that get you through daily interactions. So, you will probably need to annotate the text, underlining or highlight passages and make written notes in the margins of texts to identify the most important ideas, the main examples or details, and the things that trigger your own reactions. Devise your own notation system. We describe a general system in a box close by but offer it only as a suggestion. Keep in mind, though, that the more precise your marks are and the more focused your notes and reactions, the easier it will be to draw material from the text into your own writing. But be selective: the unfortunate tendency is to underline (or highlight) too much of a text. The shrewd reader will mark sparingly, keeping the focus on the truly important elements of a writer’s ideas and his or her own reactions.

Recall your Purpose

- What are you looking for?

- How will you use what you find? Identify the weave of the text

- Double underline the author’s explanation of the main point(s) and jot “M.P.” in the margin. (Often, but not always, a writer will tell an engaged reader where the text is going.)

- Underline each major new claim that the author makes in developing the text and write “claim 1,” “claim 2,” and so on in the margin. x Circle major point, of transition from the obvious (subtitles) to the less obvious (phrases like however, on the other hand, for example, and so on).

- Asterisk major pieces of evidence like statistics or stories or argument note in the margin the kind of evidence and its purpose, for example, “story that illustrates claim.” x Write “concl.” in the margin at points where the writer draws major conclusions. Locate passages and phrases that trigger reactions.

- Put a question mark next to points that are unclear and note whether you need more information, or the author has been unclear or whether the passage just sounds unreasonable or out-of-place.

- Put an exclamation point next to passages that you react to strongly in agreement, disagreement, or interest.

- Attach a post-it note next to trigger passages and write a brief reaction as you read. Having read through a text and annotated it, your goal in reviewing it is to re-examine the content, the structure, and the language of the article in more detail, in order to confirm your sense of the author’s purpose and to evaluate how well they achieved that purpose. When you review a piece of writing, you will often start by examining the propositions (main points or claims) the writer lays out and the support he or she provides for those propositions, noticing the order in which these arguments and evidence are presented. Making an informal outline that lists the main points, mapping out the essay, is one very effective way of reviewing a text. Here, a well-marked text will really save you time. As you work through your review, you should also tune in to the rhetorical choices the author has made, analysing how the article is put together. Ask yourself what the writer is actually claiming, and why she or he organized the piece in this way. What does the introduction accomplish? What functions do the individual paragraphs serve? What patterns of thinking does the author use to drive home the main points? Your notes already tell you what the writer says; you’re now getting at what the writing does. You will also want to make note of the tone and attitude used to support and elaborate the writer’s view. Is the writer serious or humorous? How can you tell? Does the writer seem to be offering only information or stating an opinion and backing it up? How do you know? Keep returning to the text for specific examples. Finally, as you review the text, sorting out its organization and analysing its rhetorical moves, evaluate the effectiveness of the text and the validity of the claims and evidence. At this point, you’re judging for yourself whether the initial promise of the article has been kept and how the writer’s values stack up against yours. To keep track of your ideas, use your journal: identify any questions you have after this re-reading, and note any insights the reading has provoked in you.

The Process: Reviewing

As you review texts, let the reading situation guide you. While each of the following strategies uncovers one aspect of a text, you may decide not to work with all of them or to work in this order. Also, don’t get caught up in finding the right answers to a specific set of questions. There is almost always more than one way to sort out a piece of writing.

Organize the Text

- Use the main point and claims that you have identified to create a simple outline, and then put the transitions and conclusions the writer makes in their place on the outline.

- Give a name to each subsection and explain what the writer “says” in the section and also what the section “does” to advance the flow of the text.

- Write a paragraph description of the overall pattern of the text. Feel the text.

- Write a paragraph that explores the attitude of the writer. Is she or he is serious, humorous, angry, ironic, informative, argumentative, combative?

- Skim through the text and find evidence of the attitude you suspect. Analyse the text.

- Write on your outline brief one or two sentence explanations of how each part of the text — claim or pieces of evidence, transitions — connects to each other part

- In a paragraph, explain how each part accomplishes the writer’s purpose. Evaluate the text.

- In your journal, review what you know about the author and the publication. Are they trustworthy sources for the topic? Does the writer or publication have an obvious bias?

- Review the evidence you noticed. Is there enough of it? Is each claim supported? Is the evidence concrete, referring to verifiable examples, statistics, and research?

- Review the claims the writer makes. Are they clear and logically coherent? Do they all relate to the topic? React to the text. x List the points that trigger a reaction in you.

- Free write a brief response to each trigger point. What reaction did you have on your first reading? What do you need to better understand? What is interesting to you?

There isn’t anything especially mysterious about this reading process. The main point here is that you can discover writers’ purposes, find your way into their audiences, and carry on a dialogue with them. And you can engage in reading and writing projects with greater power — greater understanding and efficiency — if you preview the text, read it with a purpose and a plan, and review the text carefully after you’ve read it. When readers try to make sense of more complex texts by starting at the first sentence and reading straight through, they tend to get hung up, missing the forest for the trees. Spending your energy reading a whole text again and again without previewing it, thinking about its title and other kinds of cues, and forming some hunches about its general organization and content is likely to be wasted effort because you won’t get to the core of a text’s meanings or see its larger significance and themes. Readers who quit reading because the text seems to make no sense should alter their reading strategy. Most of the learners that we know don’t have a lot of time to waste. Work smart. Preview, annotate and re-read.

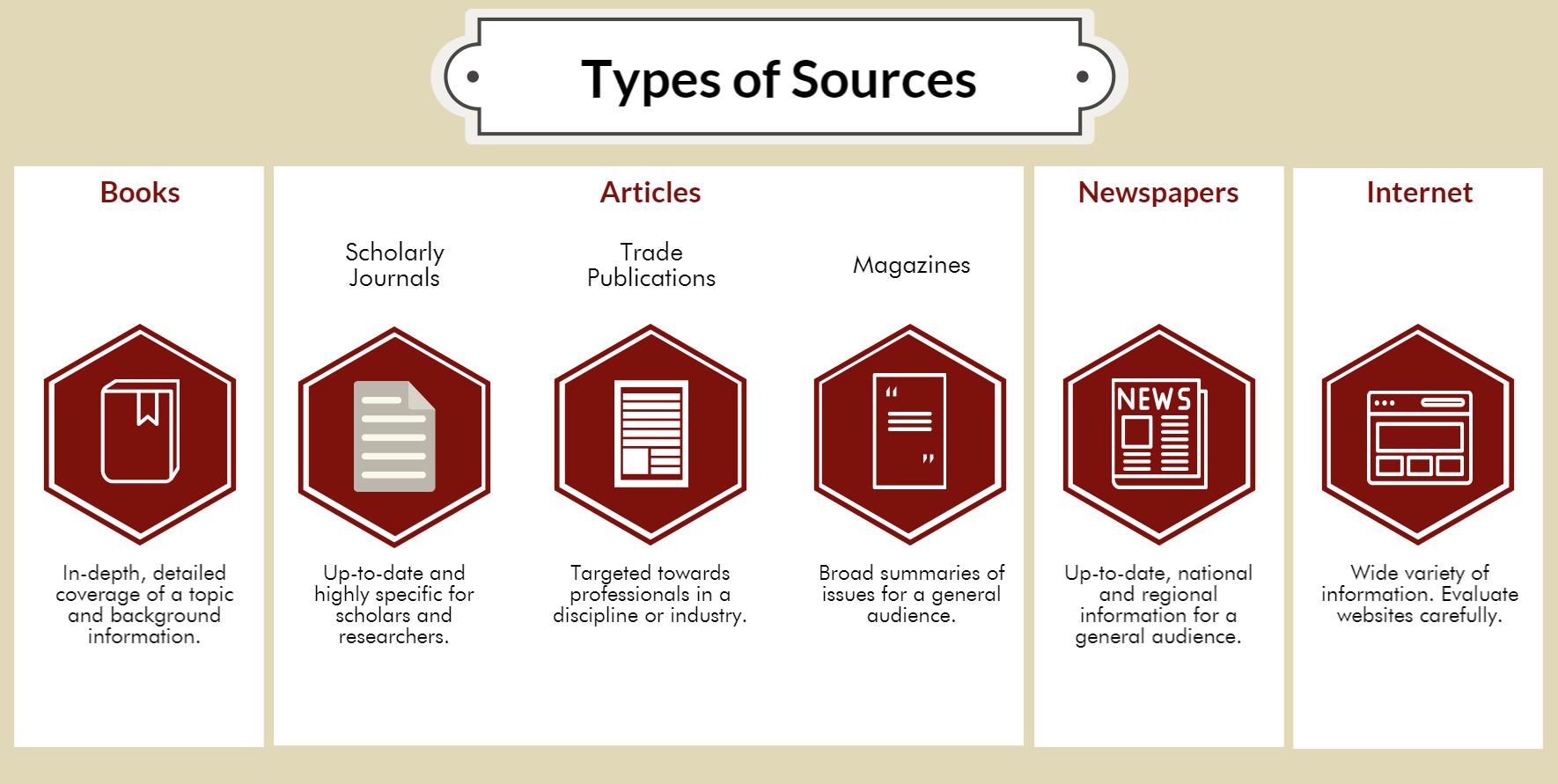

What is the Source of the Material?

Just as you might check the brand label on an item of clothing before you buy it, so should you check to see where an article or essay comes from before you read it? You will often be asked to read material that is not in its original form. Many textbooks, such as this one, include excerpts or entire selections borrowed from other authors. Instructors often photocopy articles or essays and distribute them or place them on reserve in the library for students to read.

A first question to ask before you even begin to read is: What is the source-from what book, magazine, or newspaper was this taken? Knowledge of the source will help you judge the accuracy and soundness of what you read. For example, in which of the following sources would you expect to find the most accurate and up-to-date information about computer software?

- An advertisement in Time

- An article in Reader’s Digest

- An article in Software Review

The article in Software Review would be the best source. This is a magazine devoted to the subject of computers and computer software. Reader’s Digest, on the other hand, does not specialize in any one topic and often reprints or condenses articles from other sources. Time, a weekly newsmagazine, does contain information, but a paid advertisement is likely to provide information on only one line of software. Knowing the source of an article will give clues to the kind of information the article will contain. For instance, suppose you went to the library to locate information for a research paper on the interpretation of dreams. You found the following sources of information. What do you expect each to contain?

- An encyclopaedia entry titled “Dreams”

- An article in Oprah Magazine titled “A Dreamy Way to Predict the Future”

- An article in Psychological Review titled “An Examination of Research on Dreams”

You can predict that the encyclopaedia entry will be a factual report. It will provide a general overview of the process of dreaming. The Oprah Magazine article will probably focus on the use of dreams to predict future events. You can expect the article to contain little research. Most likely, it will be concerned largely with individual reports of people who accurately dreamt about the future. The article from Psychological Review, a journal that reports research in psychology, will present a primarily factual, research-oriented discussion of dreams. As part of evaluating a source or of selecting an appropriate source, be sure to check the date of publication. For many topics, it is essential that you work with current, up-to-date information. For example, suppose you’ve found an article on the safety of over-the-counter, non-prescription drugs. If the article was written four or five years ago, it is already outdated. New drugs have been approved and released; new regulations have been put into effect; packaging requirements have changed. The year a book was published can be found on the copyright page. If the book has been reprinted by another publisher or has been reissued in paperback, look to see when it was first published and check the year(s) in the copyright notice.