The qualifications of the author to write about the subject are another clue to the reliability of the information. If the author lacks expertise in or experiences with a subject, the material may not be accurate or worthwhile reading. In textbooks, the author’s credentials may appear on the title page or in the preface. In non-fiction books and general market paperbacks, a summary of the author’s life and credentials may be included on the book jacket or back cover. In many other cases, however, the author’s credentials are not given. You are left to rely on the judgment of the editors or publishers about an author’s authority. If you are familiar with an author’s work, then you can anticipate the type of material you will be reading and predict the writer’s approach and attitude toward the subject. If, for example, you found an article on world banking written by former President Mandela, you could predict it will have a political point of view. If you were about to read an article on John Lennon written by Ringo Starr, one of the other Beatles, you could predict the article might possibly include details of their working relationship from Ringo’s point of view.

Does the Writer Make Assumptions?

An assumption is an idea, theory, or principle that the writer believes to be true. The writer then develops his or her ideas based on that assumption. Of course, if the assumption is not true or is one you disagree with, then the ideas that depend on that assumption are of questionable value. For instance, an author may believe that the death penalty is immoral and, beginning with that assumption, develop an argument for different ways to prevent crime. However, if you believe that the death penalty is moral, and then from your viewpoint, the writer’s argument is invalid. Read the following paragraph. Identify the assumption the writer makes, and write it in the space provided. The evil of athletic violence touches nearly everyone. It tarnishes what may be our only religion. Brutality in games blasphemes play; perhaps our purest form of free expression. It blurs the clarity of open competition, obscuring our joy in victory as well as our dignity in defeat. It robs us of innocence, surprise, and self-respect. It spoils our fun.

Here the assumption is stated in the first sentence – the writer assumes that athletic violence exists. He makes no attempt to prove or explain that sports are violent. He assumes this and goes on to discuss its effects. You may agree or disagree with this assumption.

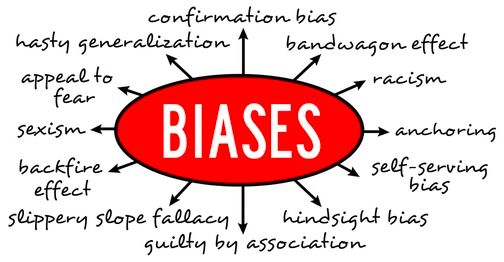

Is the Author Biased

As you evaluate any piece of writing, always try to decide whether the author is objective or one-sided (biased). Does the author present an objective view of the subject or is a particular viewpoint favoured! An objective article presents all sides of an issue, while a biased one presents only one side.

You can decide whether asking yourself these questions biases a writer:

- Is the writer acting as a reporter, presenting facts, or as a salesperson, providing only favourable information?

- Are there other views toward the subject that the writer does not discuss?

Use these questions to determine whether the author of the following selection is biased: Teachers, schools, and parent associations have become increasingly concerned about the effects of television on school performance. Based on their classroom experiences, many teachers have reported mounting incidences of fatigue, tension, and aggressive behaviour, as well as lessened spontaneity and imagination. So, what have schools been doing? At Marble Hall Farm School in Mpumalanga, parents and teachers have been following written guidelines for five years, which include no television at all for children through the first grade. Children in second grade through high school are encouraged to watch no television on school nights and to restrict viewing to a total of three to four hours on weekends. According to Amos Msimango, head of the faculty, “You can observe the effects with some youngsters almost immediately. Three days after they turn off the set you see a marked improvement in their behaviour. They concentrate better and are more able to follow directions and get along with their neighbours. If they go back to the set you notice it right away.” As Solly Ranamane has pointed out, “In the final analysis, the success of schools in minimizing the negative effects of television on their (children’s) academic progress depends almost entirely on whether the parents share this goal.”

The subject of this passage is children’s television viewing. It expresses concern and gives evidence that television has a negative effect on children. The other side of the issue – the positive effects or benefits – is not mentioned. There is no discussion of such positive effects as the information to be learned from educational television programs or the use of television in increasing a child’s awareness of different ideas, people, and places. The author is biased and expresses only a negative attitude toward television. Occasionally, you may come upon unintentional bias – a bias that the writer is not aware of. A writer may not recognize his or her own bias on cultural, religious, or sexual issues.

Is the Writing Slanted

Slanting refers to the selection of details that suit the author’s purpose and the omission of those that do not. Suppose you were asked to write a description of a person you know. If you wanted a reader to respond favourably to the person, you might write something like this: Alex is tall, muscular, and well built. He is a friendly person and seldom becomes angry or upset. He enjoys sharing jokes and stories with his friends.

On the other hand, if you wanted to create a less positive image of Alex, you could omit the above information and emphasize these facts instead: Alex has a long nose and his teeth are crooked. He talks about himself a lot and doesn’t seem to listen to what others are saying. Alex wears rumpled clothes that are too big for him. While all of these facts about Alex may be true, the writer decides which to include. Much of what you read is slanted. For instance, advertisers tell only what is good about a product, not what is wrong with it. In the newspaper advice column, Dear Abby gives her opinion on how to solve a reader’s problem, but she does not discuss all the possible solutions. As you read material that is slanted, keep these questions in mind:

1. What types of facts has the author omitted?

2. How would the inclusion of these facts change your reaction or impression?

How Does the Writer Support his or her Ideas?

Suppose a friend said he thought you should quit your part-time job immediately. What would you do? Would you automatically accept his advice, or would you ask him why? No doubt you would not blindly accept the advice but would inquire why. Then, once you heard his reasons, you would decide whether they made sense. Similarly, when you read, you should not blindly accept a writer’s ideas. Instead, you should ask why by checking to see how the writer supports or explains his or her ideas. Then, once you have examined the supporting information, decide whether you accept the idea. Evaluating the supporting evidence, a writer provides involves using your judgment. The evidence you accept as conclusive may be regarded by someone else as insufficient. The judgment you make depends on your purpose and background knowledge, among other things.

In judging the quality of supporting information, a writer provides, you should watch for the use of:

- Generalizations,

- Statements of opinion,

- Personal experience, and

- Statistics as evidence.

Generalizations

What do the following statements have in common?

- Dogs are vicious and nasty.

- College students are more interested in having fun than in learning.

- Parents want their children to grow up to be just like them.

These sentences seem to have little in common. But although the subjects are different, the sentences do have one thing in common: each is a generalization. Each makes a broad statement about some group (college students, dogs, parents). The first statement says that dogs are vicious and nasty. Yet the writer could not be certain that this statement is true unless he or she had seen every existing dog. No doubt the writer felt this statement was true based on his or her observation of and experience with dogs.

A generalization is a statement that is made about an entire group or class of individuals or items based on experience with some members of that group. It necessarily involves the writer’s judgment. The question that must be asked about all generalizations is whether they are accurate. How many dogs did the writer observe and how much research did he or she do to justify the generalization? Try to think of exceptions to the generalization; for instance, a dog that is neither vicious nor nasty. As you evaluate the supporting evidence a writer uses, be alert for generalizations that are presented as facts. A writer may, on occasion, support a statement by offering unsupported generalizations. When this occurs, treat the writer’s ideas with a critical, questioning attitude.

Statements of Opinion

Facts are statements that can be verified. They can be proven to be true or false. Opinions are statements that express a writer’s feelings, attitudes, or beliefs. They are neither true nor false. Here are a few examples of each:

Facts:

My car insurance costs R1500.

The theory of instinct was formulated by Konrad Lorenz.

Green Peace is an organization dedicated to preserving the sea and its animals.

Opinions:

My car insurance is too expensive.

The slaughter of baby seals for their pelts should be outlawed.

Population growth should be regulated through mandatory birth control.

The ability to distinguish between fact and opinion is an essential part of evaluating an author’s supporting information. Factual statement from reliable sources can usually be accepted as correct. Opinions, however, must be considered as one person’s viewpoint that you are free to accept or reject.

Personal Experience:

Writers often support their ideas by describing their own personal experiences. Although a writer’s experiences may be interesting and reveal a perspective on an issue, do not accept them as proof. Suppose you are reading an article on drug use and the writer uses his or her personal experience with particular drugs to prove a point. There are several reasons why you should not accept the writer’s conclusions about the drugs’ effects as fact.

First, the effects of a drug may vary from person to person. The drug’s effect on the writer may be unusual. Second, unless the writer kept careful records about times, dosages, surrounding circumstances, and so on, he or she is describing events from memory. Over time, the writer may have forgotten or exaggerated some of the effects. As you read, treat ideas supported only through personal experience as one person’s experience. Do not make the error of generalizing the experience.

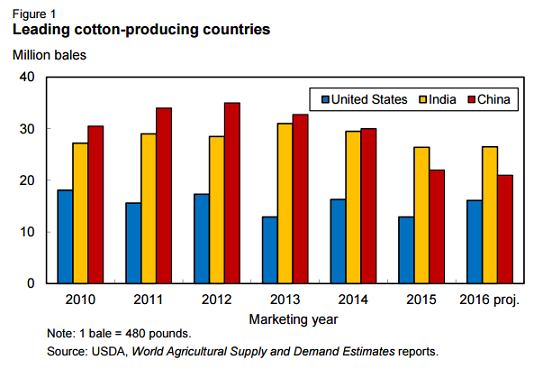

Statistics:

People are often impressed by statistics figures, percentages, averages, and so forth. They accept this as absolute proof. Actually, statistics can be misused, misinterpreted, or used selectively to give other than the most objective, accurate picture of a situation. Here is an example of how statistics can be misused. Suppose you read that magazine X increased its readership by 50 percent, while magazine y had only a 10 percent increase. From this statistic, some readers might assume that magazine X has a wider readership than magazine Y. The missing but crucial statistic is the total readership of each magazine prior to the increase. If magazine X had a readership of 20,000 and this increased by 50 percent, its readership would total 301000. If magazine Y’s readership was already 50,000, a 10-percent increase, bringing the new total to 55,000, would still give it the larger readership despite the fact of the smaller increase. Even statistics, then, must be read with a critical, questioning mind.

South Africans in the workforce are better off than ever before. The average salary of the South African worker is R30,000 per year.

At first, the above statement may seem convincing. However, a closer look reveals that the statistic given does not really support the statement. The term average is the key to how the statistic is misused. An average includes all salaries, both high and low. It is possible that some South Africans earn R5,000 while others earn R250,000. Although the average salary may be R30,000, this does not mean that everyone earns R30,000.

Does the Writer Make Value Judgments?

A writer who states that an idea or action is right or wrong, good or bad, desirable or undesirable is making a value judgment. That is, the writer is imposing his or her own judgment on the worth of an idea or action. Here are a few examples of value judgments:

Divorces should be restricted to couples that can prove incompatibility.

- Abortion is wrong.

- Welfare applicants should be forced to apply for any job they are capable of performing.

- Premarital sex is acceptable.

You will notice that each statement is controversial. Each involves some type of conflict or idea over which there is disagreement:

- Restriction versus freedom

- Right versus wrong

- Force versus choice

- Acceptability versus non-acceptability.

You may know of some people who would agree and others who might disagree with each statement. A writer who takes a position or side on a conflict is making a value judgment. As you read, be alert for value judgments. They represent one person’s view only and there are most likely many other views on the same topic. When you identify a value judgment, try to determine whether the author offers any evidence in support of the position.