A marketing plan attempts to clarify and characterise the market, the customer and the environment in which the business is being conducted. The marketing mix can be viewed as the controllable part of the marketing plan. It is the farmer’s responsibility to control these factors.

Often referred to as the four principles of marketing, product, place, price and promotion, as proposed in the well-known book by E. Jerome McCarthy entitled Basic Marketing, these four principles can be expanded to include a fifth P, being people. These five principles are referred to as the marketing mix. This section explores the application of these principles to the marketing of fresh farm products.

Product

The critical question that must be asked with regard to the product is: “What is the product and its characteristics that my target market wants?”

In order for a farmer to succeed, the product must offer clear and distinct value to the buyer. The product characteristics must also meet the expectations of the target market. Supply and demand is the ultimate judge and jury of success.

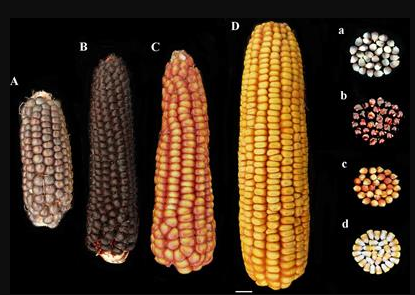

There may seem to be little opportunity for differentiating traditional crops or staple foods: after all, maize is maize. But on closer examination, it is evident that there is ample scope for product differentiation using knowledge of market opportunities as revealed by market research.

For example, there are many different maize cultivars. Even the traditional maize crop comprises many different cultivars with different properties, each with its own features and characteristics of grain size, cooking time, colour, internal quality, general appearance, taste and nutritional value.

Markets differ in their preference for different maize cultivars and specifications, and these preferences change with time.

Market differentiation can also be achieved through techniques such as organic production, distinctive packaging, and establishing a recognisable brand for the product. A product can further differentiate itself by building up a brand reputation of good quality. Consumers will come to associate a particular brand name with the product and with good quality and therefore seek this in their purchases.

The way in which the product is presented is also critical. For example, where direct delivery to the retailer occurs, such as packing for Woolworths, the product and packaging specifications are prescribed in detail by the retailer and have to be strictly adhered to.

If you are for example targeting the local processing industry, what is it that makes you an indispensable supplier to them?

If it is the bakkie trader or roadside hawker who is important to you, why would they buy your produce rather than that of your neighbour up the road?

Is your customer the impossibly difficult buyer at Pick ‘n Pay or Woolworths, who in turn is trying to meet the needs of the buyers in his fresh produce section?

Or is it the buyer in Tesco’s or Sainsbury’s in the UK (two overseas retail groups similar to Pick ‘n Pay and Spar) who is insisting on traceability, food safety standards etc, on meeting the needs of their own unique accreditation code, and in receiving the product that meets the most stringent standard the world has ever known?

Each of these markets has radically different needs and requirements, and each requires a completely different mix of product and marketing tools to successfully penetrate and maintain it.

You may be supplying all of these markets, but have you:

- Segmented them into separate entities?

- Established what each one consists of.

- Identified their individual special product needs?

Place

The critical question that must be asked with regard to place is: “Where does my target market want this product?” or more critically, “How am I going to get my product to the target market?”

Place, therefore, has to do with the distribution networks for getting the product to the customer. It is important to analyse the distribution options because the choice of channel influences the price you can charge, and consequently the profit you make.

Two questions should be asked to provide a basis for a decision on distribution:

- How can and should my product reach the consumer?

- How much do the players in each distribution channel profit?

By working through the answers to these questions it will become clearer how your product should be directed to the market.

The commonly used channel intermediaries to the consumer are wholesalers, distributors, sales representatives and retailers. For export fruit, distribution channels are highly specialised and the competitive environment enables the producer to select the appropriate inland transport provider and logistics service provider at the port terminals.

Very often decisions relating to transport and logistics are the result of negotiations with the company to whom the grower has chosen to export and market his product. Joint decisions are taken for instance on whether products will be shipped in containers or in reefer vessels.

Moving fresh fruit by air is expensive and seldom a financially viable option.

Example: Road transport of fruit into Africa is exposed to pilferage and border delays that compromise fruit quality. This leaves sea freight as the most viable transport option into Africa. Shipping lines have increased their ports of call and improved transit times to African destinations. An important issue remains to place the maximum number of cartons per pallet (payload) in order to provide the importer with optimal economic benefit on freight costs. Placing fruit into local market destinations involves a trade chain of transporters and local wholesale market agents. The choice of service providers and markets depends on the outcome of the market research

Price

The critical question that must be asked with regard to price is: At what price can I sell my product to the customer to ensure the optimum sales but also the best possible profit margin?

The price at which the product is sold is critical. This is because a high proportion of the costs involved in producing and packing fresh fruit for a particular market are fixed. Distribution costs vary depending on who does it and where the market is located. Profit is highly dependent on the price earned in the market.

It has been said that the market price is the market price – take it or leave it. This is indeed the case in well-supplied markets where large volumes of products are moved at discount prices. In this case, the retailer is able to exercise pressure on the supplier. In other cases, where the supplier or grower, has a product that is generally in short supply or is particularly desired by the market, he has more bargaining power and is in a position to more easily influence the selling price in his favour.

When the produce of a particular variety or specification is in abundance, it is more difficult for the farmer to negotiate any form of advanced payment or minimum guaranteed price with the buyer or his export agent. Under such circumstances, the farmer may be forced to send his produce to the market and hope for the best. This is called selling on consignment.

Before deciding what price to ask, the farmer should have in mind some kind of pricing strategy. For example, he might decide to work on a cost-plus basis, whereby he simply calculates his costs and adds a desired profit margin. The farmer might otherwise decide to try to penetrate a particular market by going in at a specifically low price. On the other hand, he may go in at a high price and skim the market for a short period while a competitive product is absent.

Whatever pricing strategy is followed, price is a critical aspect of the marketing mix.

Promotion

The critical question that must be asked with regard to promotion is: How can I promote my product so that my target market knows what a wonderful product I have available?

Promotion refers in essence to communication with the customer. In its simplest form, it means a message sent, a message received and a message acted upon. If the product has been produced with the needs and desires of the customers in mind, the communication necessary for getting customers to buy it is through the message used to reach them.

Promotion includes all the advertising and selling efforts of the marketing plan. Goal setting is important in developing a promotional campaign. The ultimate goal is to influence buyer behaviour, and therefore the desired behaviour must be well defined. Different products require different promotional efforts to achieve different objectives.

For example, if the intention is merely to make the market aware of your product, the promotional mission will be to inform the market about the product and to communicate a ‘need’ message. If the intention is to generate interest in the product, a compelling message is required with the idea of solving a need. If the intention is to generate loyalty, the message should reinforce the brand or image with special promotions.

Whether the idea is to pull buyers to a sales outlet or to push a retailer to stock and sell, there are five general categories of promotional effort, being:

- Advertising

- Personal selling

- Sales promotion

- Public relations

- Publicity and

- Direct selling

There are many techniques for implementing promotional efforts. In the case of promoting the sale of fresh fruit, much depends on the specific market and market segment, and on whether the promotional campaign is generic to a fruit type and farmer community, or highly specific and applicable only to the fruit of a particular cultivar from a particular farmer at a particular time. Promotions may also take the form of general media messages, or so-called above-the-line promotions, or price discounts and in-store promotions, referred to as below-the-line.

Promotions are communication tools. Which, how and when these tools are used depending on specific circumstances.

People

The critical question that must be asked with regard to people is: Who do I need and how do I need to manage my workforce to achieve the requirements of the market?

Neither efficient production nor any of the above components of the marketing mix can be achieved without a productive and motivated workforce.

Click here to download a handout with a practical example of the Marketing Mix in agriculture.