Three main factors enabling organisational culture change are:

Shared Vision/Goal

When organisation members have a shared vision, they know, and are enthusiastic about, what the organisation is trying to accomplish, and have a common view about the general mechanisms by which those goals can be achieved. A shared vision can be to the organisation or to a project within the organisation. When no shared vision exists, people often end up working at cross purposes, and there is little common agreement about what the organisation or group is trying to achieve. It is as if there were insufficient liquid added to the flour in making bread. All the kneading in the world is not likely to help it to hold together and additional flour is not likely to make a positive difference. Consequently, for people to work together, they need to see themselves as working towards common goals. In project development, the need to develop clear project goals is particularly important during difficult periods. Without it, difficulties that are encountered tend to become fatal obstacles to the project. Such goals must be worthy of the commitment of significant amounts of time and energy. The term vision, rather than the more commonly used word, objective, was chosen because it suggests that these goals must be capable of inspiring participation. Furthermore, a vision can bring people with divergent views together in a commonly agreed-upon and sustained effort. A vision implies something more than the mere number of Rands earned, or the number of items produced, or the number of health promotion courses taught, although it might include any or all of these. A vision is something that people can dream of and care deeply about as well as something that they can achieve.

Shared vision emerges when people have a chance to integrate their own personal goals and approaches with those of the organisation, programme, or project. This is particularly important in health promotion, because people have an opportunity to work toward their own health enhancement goals as part of the overall programme design. People who are working toward the achievement of their own health objectives should be in a much better position to assist others, particularly if they are able to discuss their shortcomings, strengths, and difficulties with those they are trying to help.

The development of a shared vision is contingent upon working towards a group consensus which takes the hopes and wishes of individual group members into consideration. Verbalising differences and concerns at the beginning of a project and reviewing shared decisions regularly help to not only strengthen the vision but also to improve it. If group consensus is not aspired, needed project resources and enthusiasm may not be forthcoming. Health promotion programmes stand to benefit from the process of developing a shared vision, because this process can help organisational leaders and members to see how health promotion is not an add-on to their other activities, but rather a core feature of their working together.

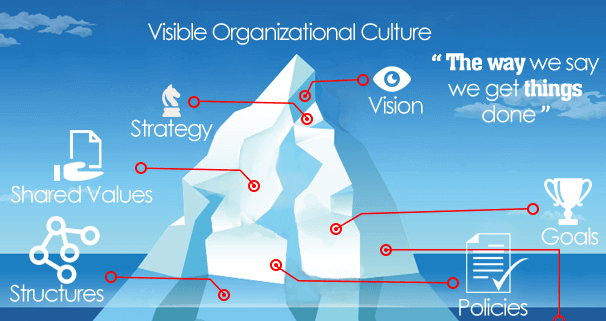

If a shared vision is to be maintained and improved, a great deal of attention needs to be paid to its communication throughout the organisation, and particularly, its communication to new organisational members. A simple and clearly-stated vision, consisting of no more than a few major statements, is more easily communicated than lengthy lists of goals and objectives. A graphic image or an acronym can be useful to communicate the vision. The vision needs to be formulated in such a way that it can be communicated during the orientation of new members, in evaluating individual and organisational performance, in organisational planning meetings, and even during social occasions. As many organisational members as possible should be able to communicate the shared vision in a few short words and be able to tell how their decisions and actions, as well as the decisions and actions of the organisation, fit with that vision.

It is the new and evolving vision of the organisation which helps new norms to crystallise where old outdated norms exist. The shared vision of the organisation enables people to see that change is both desirable and necessary. The shared vision adds direction to the change. It helps people to believe that their energies will be well spent. The shared vision offers people an opportunity to develop shared dreams and hopes. It is the common acknowledgement to shared dreams that engenders a sense of community, and it is the element of hope which enables people to work in a positive culture.

Click here to view a video on shared vision.

A Positive Culture

A positive culture was found to be a critical second factor in promoting successful culture change projects. A positive culture is founded on the belief that goals can and will be accomplished when people creatively work together toward their achievements. In a positive culture, people look for opportunities rather than obstacles, and for strengths rather than weaknesses in one another; like a fisherman who thinks he is just about to catch a fish. A member of a positive culture is poised to take advantage of opportunity. Given such a positive outlook, multiple solutions are sought for every challenge. And, people think in terms of challenges and opportunities instead of problems or defeats. In a positive culture, people realistically consider their assets and strengths as well as at their challenges and obstacles, recognising that it is the former that will enable them to overcome the latter to move towards new accomplishments.

A positive culture does not include unrealistic thinking, but rather recognition that there are positives in most, if not all, people and situations, and which they can find through creative and persistent searching. And, it is these good things rather than the negatives in the situations that provide the basis for moving forward towards greater accomplishments.

Use of the term “culture” is intended to help people distinguish between the superficial “smiling face” posters, buttons, bumper stickers, and core values. Smiles are a feature of a positive culture, but they tend to be based upon the recognition of positive outcomes and opportunities rather than on a fixed facial posture. A positive culture is not a mask to cover problems and opportunities. It is not luck, but rather an attention to opportunities which improves results. And, having a positive culture does not mean that human suffering is ignored or that human values issues are taken lightly. In a positive culture, joy is found in the process of working towards the solution of human problems.

Too often, the “nay saying” negative norms of our larger societal cultures sap energy and interfere with our achievements. To recognise the extent of this negativism, one needs only to look at the “bad news” that appears on television, in newspapers, and in day-to-day interactions.

As one psychological study demonstrated, bad news makes people think of themselves and those around them as bad. In this study, subjects who had just listened to a news broadcast reporting negative behaviour, thought worse of themselves in the experiments than those who had just listened to a news broadcast reporting positive behaviour.

In a negative culture, people tend to discount their resources and successes by looking for imperfections in the outcome. In a positive culture, imperfections are challenges for the future which can be better met because of current successes. Instead, listing successes with failures on an additive scorecard, people operating from a positive culture should be more apt to list their successes and failures separately so that the successes only could be appreciated.

In similar fashion, a positive culture tends to promote win-win solutions to problems, while challenging false dichotomies. The movement towards a positive culture makes it possible for organisational members to create the ingredients of success. A positive culture enables organisational members to create a worthwhile shared vision which is not bogged down in conditional statements or in solutions which rely on the failure of others. Furthermore, a positive culture makes such shared visions believable. And, as shall be discussed shortly, a positive culture and a shared vision can help people to establish a third ingredient to organisational success: a sense of community.

Case Study

Seattle Pike Place Fish Market on creating a positive work culture.

Years ago, a documentary filmmaker named John Christensen was visiting Seattle when he came across a group of energetic fishmongers at the Pike Place Fish Market who were throwing fish to one another, entertaining the crowds, and selling a lot of fish, to boot. He stood and watched the scene for over half an hour, wishing he had that kind of energy and fun culture at HIS place of work. It inspired him to create the video FISH! “I wanted to inspire people to work wholeheartedly, with purpose, while having fun,” Christensen said. “I saw how this passion leads to excellence.”

The market is a messy, smelly job, so why do the employees at Pike Place Fish Market have so much FUN? Well, that began in 1965 when Pike Place Fish employee John Yokoyama purchased the market from his boss. As he and his employees were deciding what kind of company they wanted to become, someone suggested they become “world famous". Everyone embraced that vision, they added “World Famous” to their logo, and began discussing how they could make that vision a reality.

Yokoyama and his employees created their own definition of “world famous". “For us,” they said, “it means going beyond just providing outstanding service to people. It means really being present with people (including us) and relating to them as human beings…intentionally being with them right now, in the present moment, person to person. We take all our attention off ourselves to be only with one another and the customers…looking for ways to serve them.”

Click here to view a video of the Seattle Pike Place Fish Market...

A Sense of Community

The third factor which was found to play a significant role in the success of culture change programmes is a sense of community. A sense of community is found when people feel as if they belong to and are part of the culture change process. This sense of belonging includes awareness that others will “care”, and, that the individual, in turn, has a responsibility to care for the other members of the culture. Furthermore, a sense of community engenders meaning and connectedness. Inclusion in the community enables members of the culture to create a shared history and common destiny. It is a sense of community which fosters cooperative actions.

A sense of community is particularly essential when change is being planned. If there is a lack of a sense of community, everyone’s resources and turf must be granted and maintained exclusively for their own personal use. Information about strengths and weaknesses are kept secret, so that people can feel protected from one another. The absence of community causes organisational members to look upon change with suspicion. Lower echelons in the organisation equate change with manipulation. Leaders fear that their positions of power and privilege will be challenged by innovation. Participatory and democratic decision-making is eschewed or used inappropriately when choices are not available. The physical and creative energy of the organisation is sapped by fear and scheming.

Too many groups and organisations endure low levels of community. Organisational members tend only to know their co-workers in terms of their limited job roles. Too many workers know little about the families of co-workers, their friends, their special interests, their hopes, and dreams. The statement “give me a pair of hands” when asking for an additional employee reflects this attitude. Cut from a sense of community, too many organisational members have resigned themselves to “put in their time”, to endure, to keep to themselves, and to hope that they survive in a hostile environment. To cope, these people form protective groups of alliances. In extreme cases, they may pay off others by looking the other way when sabotaging projects. These alliances are founded in a survival mentality which fails to activate the collective potential of the organisation.

People often dream longingly at the times they felt the community connection. Such memories may stem back to time spent in a small town, or to when the organisation was forming, or to work in a department, or even to a time of their participation in a social movement or political cause. These memories can become a powerful force in individual and collective behaviours. There can be a reluctance to give up behaviours which are associated with the memory of community. As a result, some behaviours, such as overreacting, and the abuse of alcohol, can be associated in peoples’ minds related to significant positive community-based experiences.

The creation of a sense of community adds immense power to the culture-change effort. The new meaning and historical significance associated with creating a sense of community help people to challenge older behaviours. By associating desired behaviour with the creation of community, new chosen behaviours become emotionally reinforcing and more resilient to environmental pressures. Thus, a new sense of community frees organisational members to look more critically at behaviours which they had associated on a conscious or subconscious level with community. People are then in a better position, for example, to disassociate the smoking they learned in high school from the positive experience they had in building meaningful friendships. In a culture-based health promotion programme, participants are better able to associate non-smoking with new positive bonds and meaningful experiences.

The trust and openness available in community is a necessary ingredient to collective innovation. Weaknesses and temporary setbacks need to be hidden and can be given the attention they deserve. And, given a sense of community, helping one another becomes a virtue allowing everyone to add to and to utilise available resources. These qualities of community make it possible, for example, to work on the often-hidden problems of drug addiction and emotional distress. Perhaps, most importantly, a sense of community helps all organisational members to recognise such issues as collective problems rather than strictly a concern of those directly experiencing the problem.

Although many programme participants find their community-building skills rusty, these same participants frequently give the most favourable ratings to those elements of the programme which focus on community building opportunities. Presentations and workshops which devote time to personal sharing and small-group activities tend to be those which have a lasting impact on the group or organisation. It is not uncommon for organisational members who have worked together for years, to learn about important, yet unrealised, common interests during simple sharing exercises. As sharing opportunities are scheduled into the daily workings of the organisation, a sense of community evolves, and the culture-change programme evolves forward.

In the same way that a sense of community contributes to the success of culture-based change efforts, the introduction of culture change programmes serves a critical role in creating a sense of community in organisations. One organisation that started a health promotion programme for reducing illness costs within the organisation, reported that while the organisation’s financial goals had been more than achieved, the greatest benefit by far was the opportunity that the programme provides for deepening the sense of community within the organisation. Through the programme, associates from various levels and departments in the company shared important health concerns with each other. In creating opportunities for associates to interact constructively, meaningfully, and playfully outside their normal work roles, a new appreciation of the organisation and of individual associates was created. Furthermore, the constant involvement of associates’ families strengthened bonds which were emerging in the organisation and made it possible for the organisation to be even more effective in accomplishing its goals.

Case Study

Click here to view a video on the HOPELab on having a community at work.