Energy Level

First and foremost, watch for listlessness. Healthy animals are “bright-eyed and bushy-tailed”, as the old saying goes. They are active, moving around freely. Their heads should be held up; their ears and eyes should be responsive to their environments. Their appetites should be good, and they should drink plenty of water. An animal that is just lying around, not eating, or not showing much interest in what’s going on around it is probably ill. There are some exceptions to this rule. On hot days, critters may just lie around in the shade looking pretty lethargic – but as the heat of the day breaks, they’ll get up and eat again. Still, even if they’re lethargic from the heat, their eyes and ears should be responsive to what’s going on around them.

Newborns can also be an exception to the listless rule. For the first week or two of its life, a newborn simply eats and sleeps, and its sleep tends to be very, very deep. Sometimes you’ll see a newborn baby that you’ll think has died, it’s in such a deep sleep, but if you look more closely you’ll realize it’s simply in the black depths of newborn exhaustion. Coming into the world from the safety and warmth of the womb is hard work for a little thing.

Hair and Coat

This might be considered a vanity issue, especially if critters were like people, but it’s not. Hair or wool should look shiny and healthy, and it should cover the body fairly evenly (unless you are looking at bison, which are always shaggy looking, or animals that are shedding out their winter coats in spring and early summer). Poor-quality coats can indicate nutritional illnesses, external parasites, or other systematic diseases. Also, the coat shouldn’t be caked with manure.

Manure that’s caked on the side of the body is often just a sign that the animal has been forced to lie in a manure pile and may not be of great importance. But if the manure is caked around the tail-head and down the backs of the legs, it is a sure sign of diarrhoea or scours.

Discharge

Look for suspect discharges from the nose, mouth, ears, or eyes. Sometimes the nose or the eyes may have a little bit of watery discharge, and it isn’t anything to worry about. But if a discharge is pussy looking, if there is crusty stuff built up around the muzzle or eyes, if there is excessive slobber or frothiness around the mouth, or finally, if there is any kind of discharge from the ears, the animal is not well.

Hydration

Look at the eyes to see if they appear “sunken”. This is usually a good indication of dehydration. Dehydration often accompanies scours or illnesses that cause a fever. If you can view the gums and the tongue, typically they should be light pink. If they are grey or white, chances are the animal is in shock, either from an injury or from dehydration accompanying an illness.

Breath Sounds

Listen for any coughing or wheezing. Healthy animals breathe easily through their noses, not their mouths.

Mastitis

The last external check is done exclusively on milking animals. Though most common in dairy cows, mastitis can occur in any female animal that is producing milk in her udder – even a pregnant animal that hasn’t given birth yet. On rare occasions, a young female that hasn’t even bred yet can develop mastitis. A healthy udder should be warm, but not hot; pink, but not red; and soft, but not hard. The milk should flow smoothly and, except for colostrums, should be very liquid with no clots or lumps in it. Colostrums are almost like pudding, it’s so thick, but they shouldn’t have any lumps in them after the first few squirts.

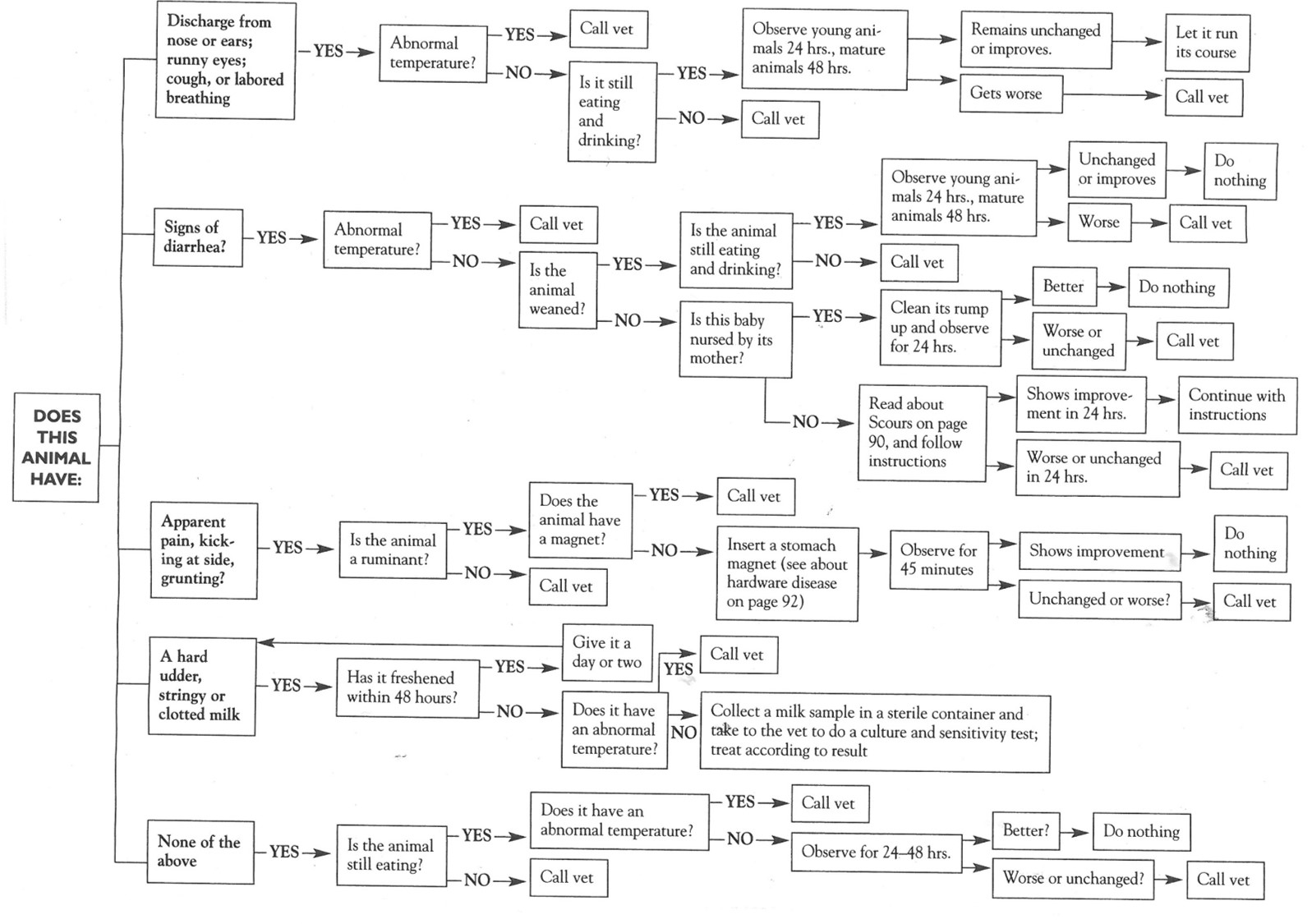

If after making these external observations, you suspect an animal isn’t well, remove it to a quiet and secluded location. This will allow further evaluation and treatment, and hopefully, reduce the likelihood of an illness being passed to healthy herd mates. If the animal is tractable, check its body temperature. Animal’s normal temperatures run in a slightly wider range than ours do, but if your animal has an elevated or a subnormal temperature according to the table below, it’s definitely time to make some decision. The figure shows some criteria we use in deciding whether or not it’s time to call the veterinarian. There is, of course, a certain degree of flexibility in applying this, and as your nursing experience and comfort level increase you may wait longer to call. (Some vets or other farmers may disagree with this system, but it has worked for us.)

Click on the link/s below to open the resources.

Live Stock Handler Training Manuals

Click here to view a video that explains the physical examination of sheep.

Click here to view a video that explains the physical examination of cows.