There are hundreds of different ailments that can cause problems and thousands of different causative agents for those ailments. As you get more involved in animal agriculture, you’ll need to get at least one or two books that specifically address animal health. The few illnesses that will be mentioned here are some of the most common problems that farmers deal with, but even these can be the result of myriad causative agents. Read more and talk to your professional veterinarian.

|

|

Scours

In adult animals, scours aren’t usually fatal. Most often, adult diarrhoea is the result of a change in diet or of consuming very lush pasture. Cases of diarrhoea caused by diet change will clear up in two or three days, and don’t have many other symptoms than the diarrhoea itself. Lush-pasture diarrhoea will continue for as long as the high-quality, moist feed lasts; but, like change-of-diet cases, it doesn’t tend to have other symptoms associated with it. If you haven’t adjusted the animal’s diet, or it’s not on lush pasture, the next most common cause of adult scours is excessive parasite loads. Parasitic scours typically aren’t accompanied by a fever, but the animal will appear lethargic, and its coat may be dull. Diagnosis of parasitic scours requires a stool sample to be checked by your vet (unless you actually see worms in the stool). If an adult animal is both suffering from diarrhoea and running a fever, it’s probably time to call your veterinarian. The animal is either suffering from a viral or a bacterial cause of scours.

Scours in baby animals – say, less than a month old – is always a very serious and life-threatening situation. Normal baby animal stools are yellowish and tend to be kind of gooey, life soft Silly Putty. Sometimes the stools may stick to the tail-head for the first day or two – during the fly season, this should be wiped away, if possible, to prevent screw flies from laying their eggs in the mess. The eggs develop into maggots, and the maggots don’t stop eating when the manure is gone. In short order, they can do terrible damage to the baby animal, possibly even causing death.

With scours in very young animals, the stool becomes watery, or sometimes slimy, and if left untreated the baby will die within a few days. Scours is quite common in bottle babies – those being fed by humans instead of their mothers. The most prevalent cause of scours in bottle babies is overfeeding, especially of milk. The scours caused by overfeeding is the most easily cured kind, but without treatment, it can take an otherwise healthy baby animal out in just a few days.

Other causes of scours in babies include the bad guys: bacteria, viruses, and parasites. One of the worst bad guys that we’ve had personal experience with is K-99 Escherichia coli. E. coli is a common and generally beneficial bacterium found in the gut of most animals. There are many strains of E. coli, but the strain that microbiologists have dubbed K-99 is highly contagious in baby animals during the first few days of life, and it’s very deadly. Once we knew what the problem was, we were able to treat all the rest of the calves that were born that summer with a colostrums supplement of K-99 antibodies. K-99 scours sets in within the first 3 or 4 days of life. Common causes of scours in the 5- to 15-days-of-life range include rotavirus and coronavirus; at 2 to 6 weeks of life, salmonella species of bacteria are the primary culprits.

Treatment for Scours

Treatment of scours should be instituted as soon as the problem is recognized. The first thing to do is replace fluids and electrolytes. Electrolytes are basically the “salt” molecules that are normally found in the bloodstream and include such elements as calcium, potassium, sodium, and magnesium. Commercial electrolyte solutions are available at most feed stores, farm supply houses, or from your vet. We always made a homemade concoction. Electrolyte therapy is good not only for scours but also for any illness that might cause dehydration. With an adult animal, simply provide a pan of water that has electrolytes mixed in.

If you’re treating a baby animal, dilute its normal milk ration by half with water. Between the milk feedings, feed it a comparable ratio of your electrolyte solution. For example, if an 80-pound (36.3 kg) calf is receiving 4 quarts (3.8 L) of milk per day (a whole-milk ration that weighs approximately 10 percent of its body weight) during two feedings, mix 1 quart (0.95 L) of whole milk with 1 quart of water at each feeding. Between the two daytime feedings, and again just before bed, feed it 12 quarts (1.9 L) of electrolyte. Don’t feed the electrolyte with the milk, because the digestive process interferes with the absorption of the electrolytes into the animal’s system. Babies suffering from the overeating version of scours require no more treatment than this, but you should continue it for 2 to 4 days or until the stools return to normal. If you do suspect that the scours is being caused by a pathogen, antibiotics may be in order – check with your vet.

If the animal you are treating for scours is a ruminant, helping its normal flora return is crucial. The best way I know of, if you can get close up to a healthy herd mate that is chewing its cud, is to reach into its mouth and grab out the bolus of cud before the animal knows what hit is (yes, it’s gross the first time you do it); then insert the bolus as far as possible down the throat of the ill animal, so that it swallows the bolus. The bolus from the healthy animal is full of good bacteria and acts to recharge the ill animal’s system.

Bloat

Limited to ruminants, bloat is a hazard when you’re using a grazing system. Bloat is caused when excessive quantities of gas become trapped in the rumen; in extreme cases, it can be deadly within an hour or two. It is usually the result of eating lush, leguminous pasture, and is aggravated by moisture from dew or rain. It is most common on alfalfa, slightly less common on clover, and doesn’t happen on bird’s-foot trefoil pastures. Pastures with a high percentage of grass compared to legumes are the least likely to cause bloat, but even these can do it in early spring.

The most prominent symptom of bloat is a bulge on the animal’s left side, just below the spine and in front of the hip bone. This area usually appears caved in, but in a bloating animal it sticks out. Bloating animals also quit eating and quit belching.

Ruminants on pasture need to be watched for the first signs of bloat, especially in spring. To avoid it in the first place, limit access to lush pasture first thing in the morning, or right after rain until the animals are well acclimated to the pasture. Feed some hay prior to turning them onto pasture and leave them on pastures for short periods of time – 45 minutes to an hour is good to start.

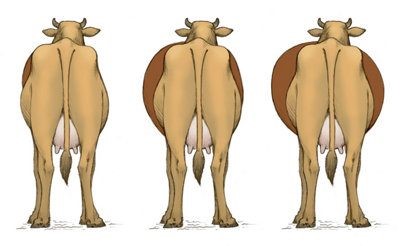

Cattle bloat can range from mild to heavy to dangerous.

Treatment for Bloat

Normally you have cases of bloat at the start of each grazing season. For cows, administer a mixture of 1 cup (236 ml) cooking oil, 1 cup (236 ml) water, and 3 tablespoons (44 ml) baking soda, and mix well. (A squirt water bottle – the kind bike riders and hikers use – works well, just dribble the contents into the animal’s mouth over a few minutes. They don’t get it all, but they get enough.) Sheep and goats are much less likely to suffer bloat, but if they do, administer about one-fourth of the above mixture. After the animal drinks its “medicine”, tie a stick in its mouth – sort of like a bit. This gets the tongue working, which helps kick-start the belching process.

As soon as the animal begins belching, you can watch its side go back down. In serious cases, a stomach tube can be passed down the animal’s throat and into the rumen; the gas escapes out the tube. Stomach tubes can be purchased, but in a pinch use 10 feet (3.1 m) of garden hose, with any sharp edges filed smooth.

The last resort, and it should be used only in life-or-death situations, is to cut right through the animal’s side and into its rumen. Vets carry a two-part tool for this purpose, called a trocar and cannula. In lieu of the trocar and cannula, a sterilized knife (boil in water, or soak in bleach, for about 5 minutes) might save the animal’s life. In either case, the animal will need to be placed on antibiotics, because the infection is bound to follow cutting into the rumen.

Hardware Disease

Unless you purchase a piece of completely bare land that has never had any buildings on it, chances are that you will, at some point, come up with hardware disease if you have any cows. Even baby calves can suffer from it. Sometimes it can happen in other ruminants, but it’s most prevalent in livestock.

Hardware disease is caused when the animal eats a sharp piece of metal, such as a nail or a small hung of wire. The piece becomes trapped in the reticulum and can puncture the wall. Symptoms include obvious pain, kicking at the side, a slight rise in temperature, and getting up and lying down repeatedly. If left untreated, death may result.

Treatment for Hardware Disease

The cure, at least, is simple. Insert a cow magnet in the cow’s stomach to “catch” the hardware. Some livestock men insert magnets as a matter of course into all their animals; we simply kept magnets on hand, in our vet supplies, and inserted them when an animal showed the signs. If the problem is indeed hardware disease, the animal recovers almost immediately when the magnet is inserted.

Inserting a magnet can be done by hand or with the help of a bolus, or balling, gun. Much like feeding a pill to a dog, the goal is to get the magnet all the way down the back of the animal’s throat so that it swallows the magnet. When done by hand on a full-grown cow, you must insert your arm into the cow’s mouth, halfway up to the elbow! The magnet remains in the animal’s reticulum for the rest of its life and attracts and holds onto any pieces of metal the animal swallows.