The basic principle of vaccination is that a disease-causing agent is given to an animal in a killed or weakened form (or in the form of proteins genetically engineered to look like a disease-causing agent), in order to stimulate the production of antibodies to fight off the disease.

Why do we vaccinate livestock? Of course, the reason is to attempt to prevent disease. However, if our timing is wrong, we can actually make the conditions worse.

Vaccination isn't the same as immunization. When we vaccinate, we hope that immunization occurs — but this isn't always the case. In order to have good immunity, the calf must be able to respond to vaccination. This simple premise is often overlooked because we tend to take immunity for granted.

There are several reasons that vaccinations may not result in immunity, but the most common is probably stress-related.

These stressors cause the release of a host of hormones that will hamper the immune response. Cortisol is possibly the most important of these hormones. It's so effective in shutting down the immune system, it's commonly used to control hyper immune reactions (allergic reactions) in people.

In order for the stressed animal to respond to vaccination, we must allow the animal time to recover from his stress episode. Wait at least 12 hours after arrival before processing.

Vaccinating livestock while they're still under stress is kind of like swinging the bat before the pitcher releases the ball. It's simply going through the motion. We can say the job is done, but we can't say it was done well or done right.

If the job is to be done well, we must apply the principles of good animal husbandry: clean water, high-quality feed, a comfortable place to rest and time to rest. If these are provided, the animal will be able to clear these excessive stress-related hormones from the bloodstream. Once this occurs, the animal will have a greater chance of responding to the vaccines and should actually become immunized.

Immunity isn't automatic. It shouldn't be taken for granted that just because we administered a vaccine to an animal, it is immunized. We have to give the animal the best opportunity we can to develop immunity.

When you look at the vaccines available for a particular disease, it's tempting to view them as equal, but there may be vast differences in what they actually do or are designed to do.

Many producers are well versed in the tradeoffs between using killed (inactivated) and modified-live virus (MLV) vaccines. Generally, killed vaccines work by stimulating humoral immunity — where viral or bacterial antigens induce an immune response. The result is the production of antibodies that circulate in the bloodstream and bind with the disease-causing bacteria or virus and neutralize them.

MLV vaccines, on the other hand, stimulate cell-mediated immunity (CMI), as well as humoral immunity. In simple terms, CMI works at the cellular level to destroy viruses that take over normal cellular function in order to replicate themselves.

Depending on how a particular disease organism works, killed vaccines may be sufficient. In other cases, MLV vaccines may be required to offer adequate protection. Hollis says a classic example is infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR). Managing the disease requires CMI to attack and kill the virus within the cells; the humoral immune response isn't effective by itself.

But even vaccines of the same type can provide different levels of protection. In fact, vaccine labels describe the level of protection.

Injections (parental administration) and Vaccination of Animals

This implies injecting a substance into the body of the animal. The administration thereof also requires, with a few exceptions, the cleaning of the skin (with a disinfectant) as well as the disinfection of the lid of the bottle containing the drug which is to be used. Care must be taken when working with live vaccines. (e.g., vaccines against virus diseases) so as not to destroy the vaccine in the process of cleaning. Sterile needles and syringes should be used (sterilisation should preferably be done by boiling the instruments in soft water for 20-30 minutes). The person giving the injection should possess a sound knowledge of the anatomy of the animal regarding the muscles, veins and nerves. The animal must be effectively restrained for the correct technique of administration. After the needle has been pushed into the injection site, it is advisable to connect the syringe and draw back the plunger to ensure that the needle is correctly placed. (Withdrawal of blood into the syringe is an indication that a blood vessel has been penetrated). Where possible, a clean needle should be used for every animal to prevent the transmission of diseases and germs.

Routes used for Injections

There are various methods for vaccinating livestock:

- Subcutaneous

- Intramuscularly

- Intravenous

- Intra-mammary

- Intra-vaginal and intra-uterine

- Rectal

Subcutaneous

Here the drug or vaccine is injected under the skin. The drug is taken up slower and over a longer period, as is the case with the other routes. Irritant drugs should not be injected subcutaneously. A site is chosen where the skin is loose and thus easily pulled away from the muscle or carcass.

Most of the vaccines are administered just under the skin by lifting up the skin between the thumb and forefinger and injecting the prescribed amount (usually 1-5cm) in the space between the skin and muscle or the rest of the body.

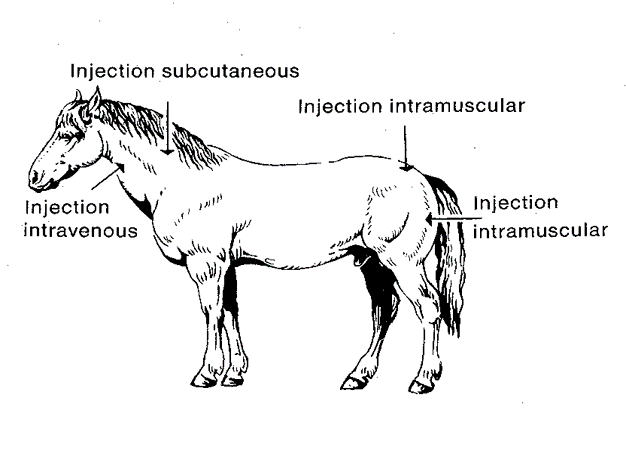

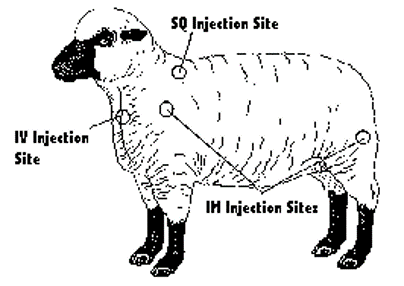

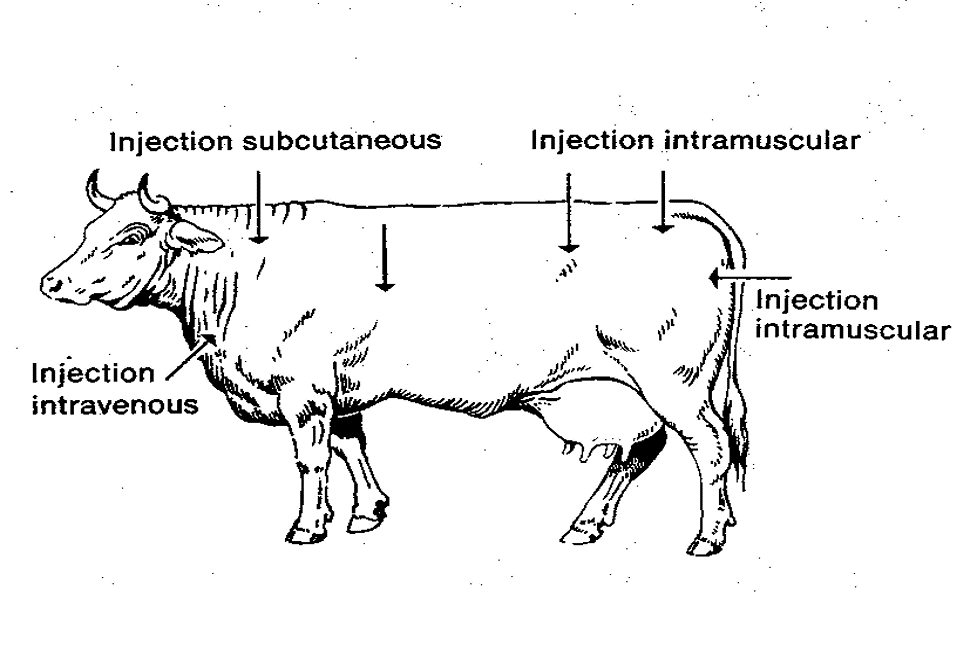

Horses, livestock, sheep and goats: The loose skin in the region of the dewlap or breast, the side of the neck or over the shoulder is used.

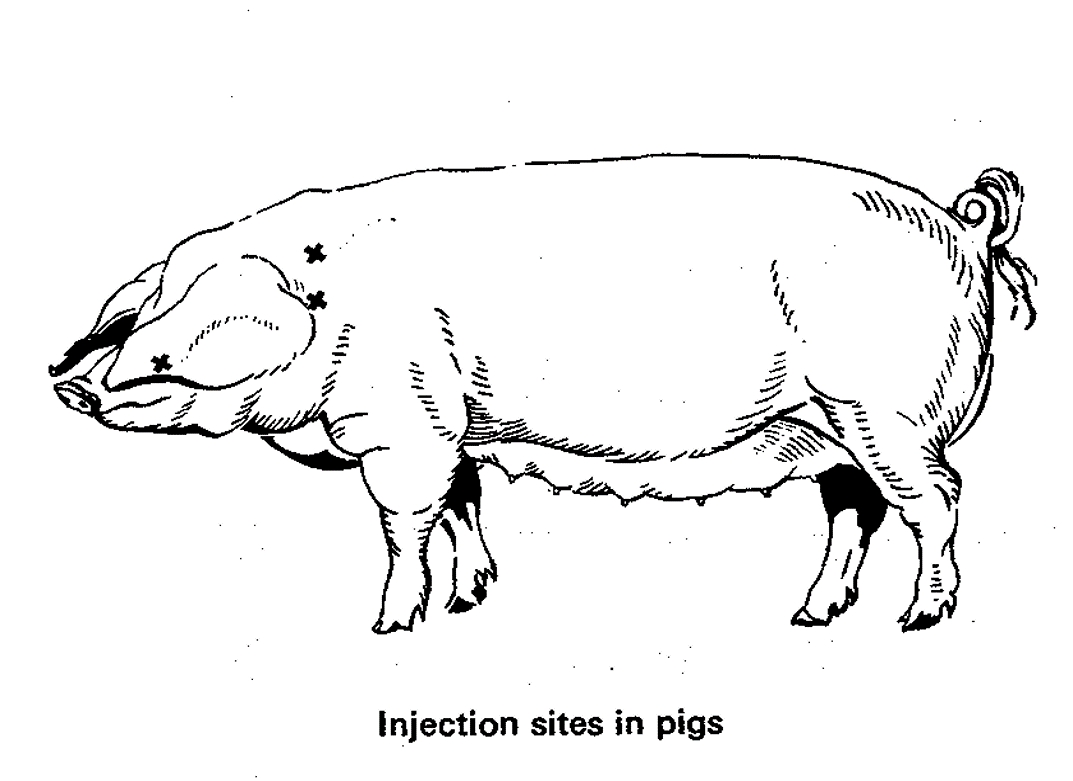

Pigs: are Just behind the ear.

Intramuscular

Here the drug is injected into the muscles. A sufficiently long needle should therefore be used to penetrate into the muscle. Small volumes should be injected in any one site (not more than 20ml per site in the case of large animals). Pain and lameness may occur when large quantities are injected at one site. Absorption of the drug is rapid due to a good blood supply to the muscle. You must make sure that the correct muscle is used and that the needle does not enter or damage the nerves and arteries. The choice of the injection site depends upon the thickness of the muscles at that site.

Horses: Preferably in the breast muscles at the bottom of the neck, although, the neck muscles may also be used (see illustration).

Livestock, sheep, goats and pigs: The muscles of the neck, rump or buttocks are the most suitable. Piglets are injected into the neck muscles behind the ear.

Poultry: Injects into the breast muscle.

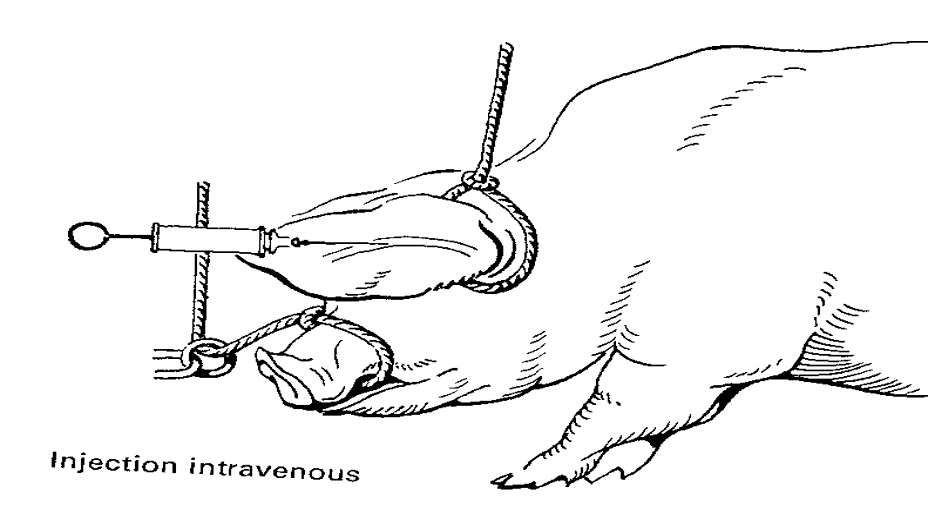

Intravenous

In this caste, the drug is introduced into a vein, in other words, directly into the blood. Various advantages derive from this as the drug is immediately available to the body and larger volumes and more irritant substances may be administered at one time. Drugs are usually introduced slowly, while the animal is kept under control. The technique of administration is as follows:

If the jugular vein is used, place a rope around the neck just in front of the shoulder and tighten the rope. This causes the blood to accumulate in the vein, rendering it clearly visible. The needle (not connected to the syringe) is pushed through the skin with a stab movement into the vein. If the needle entered the vein (and not into the wall of the blood vessel or the subcutaneous tissues) blood will flow freely through the needle. Fit the syringe, release the cord and inject the drug slowly.

Horses, livestock: Jugular vein.

Sheep and goats: Jugular vein and also the vein on the inside of the front leg, just above the knee.

Pigs: Vein in the ear. The technique is the same as for large animals except that the cord is placed at the base of the ear.

Dogs: Front leg.

Poultry: Into the vein of the wing.

Intro-Mammary

This method is used for the treatment of mastitis. Clean the teat thoroughly. The nozzle of the tube or plastic syringe (specially designed for this type of injection) is inserted into the teat canal. The contents are then squeezed into the udder, which is massaged upwards a few times. Special teat cannulas can also be used.

Intra-Vaginal and Intra-Uterine

In this case, the drug is introduced into the vagina or the uterus by hand. Absolute hygiene is necessary, and the hand used in the operation, must be washed and disinfected, or a sterile glove should be worn. If it is impossible to insert the drug by hand (e.g. fluids) it should be deposited by means of a sterile tube or catheter that is used in the same manner/technique as for artificial insemination.

Rectal

This means the introduction of suppositories, tables or liquid medicaments into the rectum, mainly for the treatment of constipation.

Complications following injections are as follows:

- Abscesses may develop at the injection site, especially when proper hygiene has not been maintained.

- Anaphylactic shock or allergic reactions may follow the administration of certain antibiotics or biological substances e.g. antisera.

- When irritating drugs were injected into a vein but leak into the subcutis, large areas of the skin may peel off leaving unsightly wounds.

- The use of certain vaccine (pyrogenous) substances may cause a fever.

- Administration of incompatible substances may result in severe systematic reactions.

Click here to view and download a handout that explains the route of application to treat the parasites.

Click here to view a video that explains injecting techniques for sheep.