Septicaemia

When a newborn animal has septicaemia, it has disease-producing organisms or toxins in its blood. Septicaemia in newborn animals is usually the result of a bacterial infection that occurs while the newborn animal is in the uterus or during, at, or immediately after birth. The route of infection can be the blood of a sick dam, an infected placenta, the newborn animal’s umbilical stump, mouth, nose (inhalation), or wound. Septicaemia is the most severe medical problem that a newborn animal can develop because the blood-borne infection disseminates and damages many different organs. The bacteria that cause septicaemia in newborn animals, many of which are characterized as gram-negative bacteria like E. coli and Salmonella, are difficult and expensive to treat, and the survival rate is low. Early signs of septicaemia may be subtle but affected newborn animals are usually depressed, weak, reluctant to stand, and suckle poorly within 5 days of birth. Swollen joints, diarrhoea, pneumonia, meningitis, cloudy eyes, and/or a large, tender navel may develop. Fever is not a consistent finding in septicaemia newborn animals; many have normal or subnormal temperatures. Most septicaemia newborn animals have a history of inadequate colostrum intake.

Diarrhoea

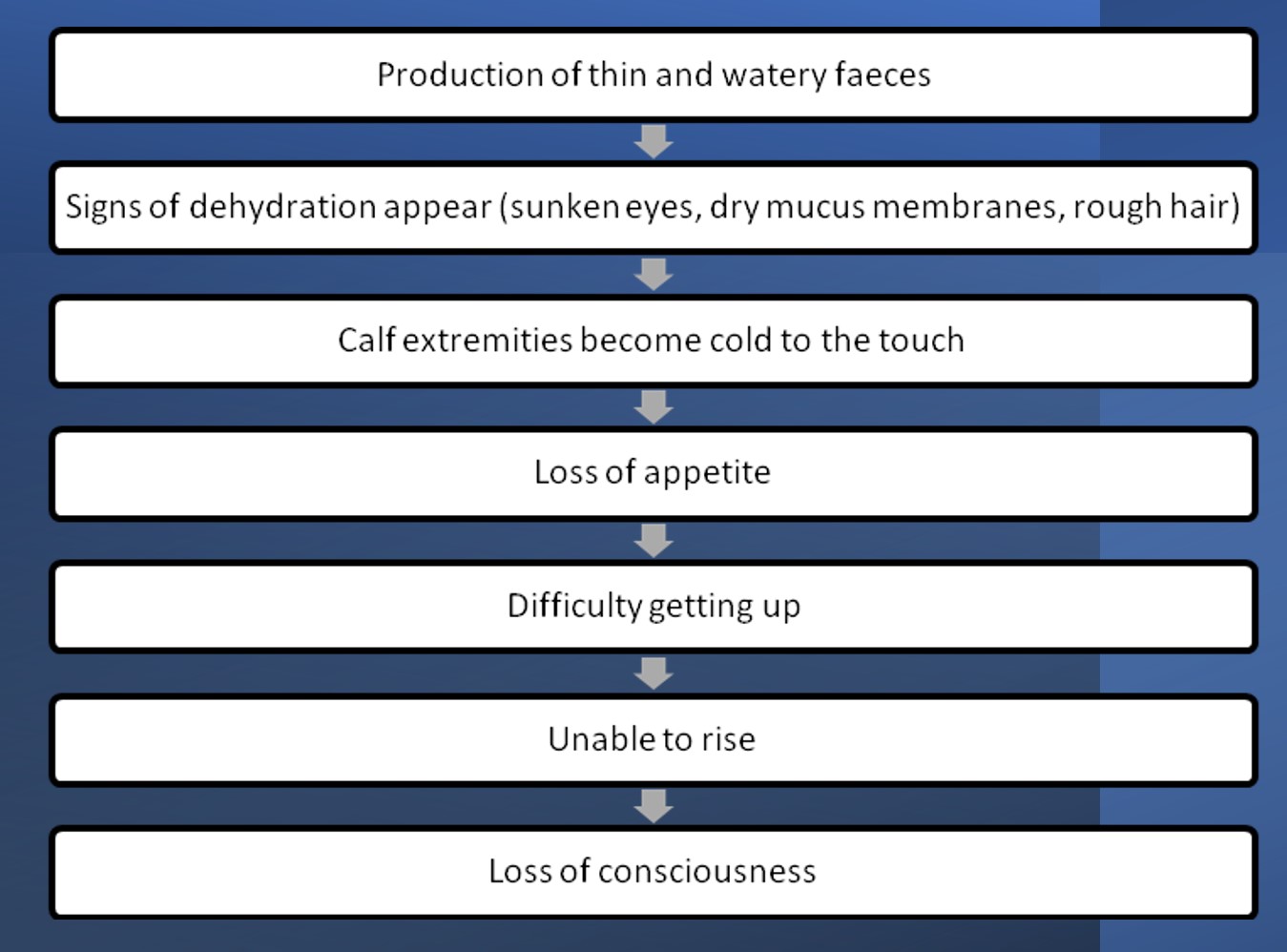

Diarrhoea is the most common cause of death in young newborn animals and is almost entirely avoidable by good management. The highest risk period for diarrhoea is from birth until about 1 month of age. Clinical signs of diarrhoea begin with loose faeces and can progress to a semi-comatose state.

Clinical Signs of Diarrhoea

Bacteria, viruses, and/or parasites cause diarrhoea in newborn animals. Usually, the newborn animal is infected with more than one agent. Typically, the virus, bacteria, or parasite is identified from a faecal sample or from the intestines of a dead newborn animal. The agents can be isolated from healthy newborn animals and adult cows as well as newborn animals with diarrhoea. Some faecal bacterial isolates, E. coli, Clostridium perfringens, and Campylobacter, are normal intestinal flora. The veterinarian uses the findings from faecal or intestinal exams to determine the most likely cause of the diarrhoea problem and to revise vaccination, treatment, and disinfection protocols. Knowing the potential pathogen provides insight into the infection source as well as the relevant factors that may have triggered the outbreak. When Salmonella is isolated, antibiotic sensitivity patterns guide the treatment protocols. When viruses and parasites are isolated, the use of antibiotics is not indicated.

The agents commonly incriminated in newborn animal diarrhoea outbreaks are listed below. The age of onset of diarrhoea can be used as a guide to the agents most likely to be involved. Unfortunately, the colour and consistency of the faeces are not reliable indicators of the cause of diarrhoea.

E. coli

- Most newborn animals are affected within the first 3 days of life.

- There are many types of E. coli: some are normal flora; different types cause septicaemia; others are invasive; enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) is the most common cause of diarrhoea.

- Special tests are needed to identify E. coli as ETEC.

- Dehydration is usually severe and may cause death before diarrhoea develops.

- The course of the disease is rapid: from weakness, diarrhoea, and dehydration, to death can be less than 24 hours.

- Antibiotics rarely affect the outcome of this disease; fluid support is critical to survival.

- Vaccination of dry cows and good colostrum feeding can eliminate this problem.

Salmonella Species

- This is an important cause of diarrhoea, and infected newborn animals are at risk of developing septicaemia.

- This bacterium can also cause pneumonia.

- Effective antibiotics should be used to prevent bacteraemia.

- Infections usually occur in 5- to 14-day-old newborn animals.

- Blood and casts of intestines may be seen in the faeces.

- New-born animals are slow to respond to treatment and are often sick for 1 to 2 weeks.

- Salmonella Dublin infection can make cattle carriers/shedders for life.

- This organism may be found in unpasteurized waste milk.

- People (especially children) handling newborn animals that are shedding Salmonella can contract Salmonellosis and become ill.

Clostridium Perfringens Type C

- There are several types of Clostridium Perfringens Type C that can be a cause of diarrhoea.

- More typically, this causes sudden onset of weakness or death.

- Colic or nervous system signs may be seen before death.

- A post-mortem examination has a characteristic haemorrhage in the intestines.

Campylobacter Spp.

This is frequently isolated but rarely the cause of newborn animal diarrhoea.

Rotavirus

- Rotavirus is found in the faeces of many newborn animals between 1 and 30 days of age.

- There are more than one group and serotypes of rotavirus; the conventional vaccine covers the most important one. A newer product offers some additional strains.

- Not all newborn animals with rotavirus have diarrhoea.

- Diarrhoea usually develops between 3 and 7 days.

- Colostrum from vaccinated cows may protect newborn animals for up to 4 days.

- The infection may be short-lived, but the intestinal lining has to recover from damage.

Coronavirus

- Like rotavirus, it is commonly found in newborn animals, not all of which have diarrhoea.

- Intestinal lining damage is more severe with Coronavirus than with rotavirus; because of this, other pathogens can collaborate to produce a severe diarrhoea episode.

- Faecal shedding pattern and diarrhoea onset are similar to rotavirus.

- Colostrum from vaccinated dams will help prevent the disease in newborn animals up to 4 days of age.

- This has been implicated as a cause of winter dysentery in adult cattle.

Bovine Diarrhoea Virus (BVDV)

- This virus can cause diarrhoea in young newborn animals, but it is rarely the cause of young newborn animal diarrhoea.

- One of the strains is capable of producing a bleeder syndrome in newborn animals between 4 and 10 weeks of age if they are infected shortly after birth.

- The virus may also be a factor in cases of pneumonia that develop after weaning.

Cryptosporidium Parvum

- This is an important parasite that is very prevalent in dairies and is capable of producing diarrhoea by itself or in combination with other agents.

- New-born animals usually are infected shortly after birth and develop diarrhoea about 5 or 7 days of age.

- Organisms can be found in a faecal smear.

- The organisms survive well in the environment.

- New-born animals that do not have good colostral immunity or that are stressed by cold or inadequate nutrition are particularly susceptible.

- Colostral immunity is not completely protective.

- A commercial vaccine is not readily available.

- Currently, there is no treatment that “kills” the organism in an infected newborn animal.

- Many infections are inapparent.

- Some preventative treatments can delay the shedding of the oocyst in faeces.

- This small parasite can cause diarrhoea in humans.

Eimeria spp. (coccidiosis)

- Two species are considered important in cattle.

- New-born animals between 7 days and 4 to 6 months are considered to be at risk.

- Four products commonly used in new-born animals are amprolium (Corid®), decoquinate (Deccox®), Lasalocid (Bovatec®), and Monensin (Rumensin®).

- Products work at different stages of the life cycle and stop development or kill the organism.

- Once newborn animals develop diarrhoea, this is a very difficult disease to treat.

- Subclinical infections impair the newborn animal’s resistance to other infections and decrease growth.

Giardia spp.

- Under unusual circumstances, these protozoa may cause diarrhoea in 2- to 4-week-old newborn animals; it is not a major pathogen.

- The organism can be found in the faeces of normal newborn animals.

- Despite the fact that the agents differ, the resulting enteritis is remarkably consistent in terms of the presenting clinical picture. New-born animals with diarrhoea consistently have some degree of dehydration. Dehydration may be life-threatening and can be assessed by observation of typical clinical signs.

Assessing Dehydration

|

Clinical Sign |

Percent Dehydrated |

|

Few clinical signs |

<5% |

|

Sunken eyes, skin tenting for 3-5 seconds |

6-7% |

|

Depression, skin tenting for 8-10 seconds, dry mucous membranes |

8-10% |

|

Recumbent, cool extremities, poor pulse |

11-12% |

|

Death |

>12% |

In most cases of fatal diarrhoea, the newborn animal dies of dehydration and loss of electrolytes, not from the infectious agents that triggered the diarrhoea. Blood glucose levels are low, and hypoglycaemic coma can develop in newborn animals that are in cold housing and have milk or milk replacer withheld for more than one feeding. Electrolyte abnormalities involving potassium, bicarbonate, and sodium are frequently found, but these resolve rapidly when fluids are given to correct the dehydration and newborn animals have access to water. For this reason, the treatment of newborn animals with diarrhoea is primarily supportive. The most important aspects are early recognition and aggressive fluid therapy. Prompt treatment with oral fluids and electrolytes is necessary for the successful treatment of diarrhoea.

Fluid Requirements for Treatment of Diarrhoea

|

New-born Animal Health |

% Dehydrated |

Daily Milk |

Oral Fluids |

|

Healthy new-born animal |

0% |

4.4 kg |

0 kg per day |

|

Mild diarrhoea |

2% |

4.4 |

1.1 kg per day |

|

Mild diarrhoea |

4% |

4.4 |

2.2 kg per day |

|

Depressed |

6% |

4.4 |

3.3 kg per day |

|

Very ill |

8% |

4.4 |

4.4 kg per day |

|

Recumbent |

>10% |

4.4 |

Need intravenous fluids |

|

Should be fed separately from electrolytes. |

|||

Click here to view a video that explains neonatal scour and diarrhoea in the calf.

Click here to view a video that explains the identification and treatment scours.