The extent to which leaders can create excitement about the organisation’s vision depends on the process applied to establish that vision. Ultimately, leaders want to create a vision that is understood by everybody, that creates shared meaning and to which people will commit themselves. A shared vision thus needs to be created.

At the heart of building shared vision is the task of designing and evolving ongoing processes in which people at every level and in every role of the organisation can speak from the heart about what really matters to them and be heard – by top management and each other. The quality of this process, especially the amount of openness and genuine caring, determines the quality and power of the results. Stephen Covey refers to this as: ‘no involvement, no commitment’.

Building a Shared Vision

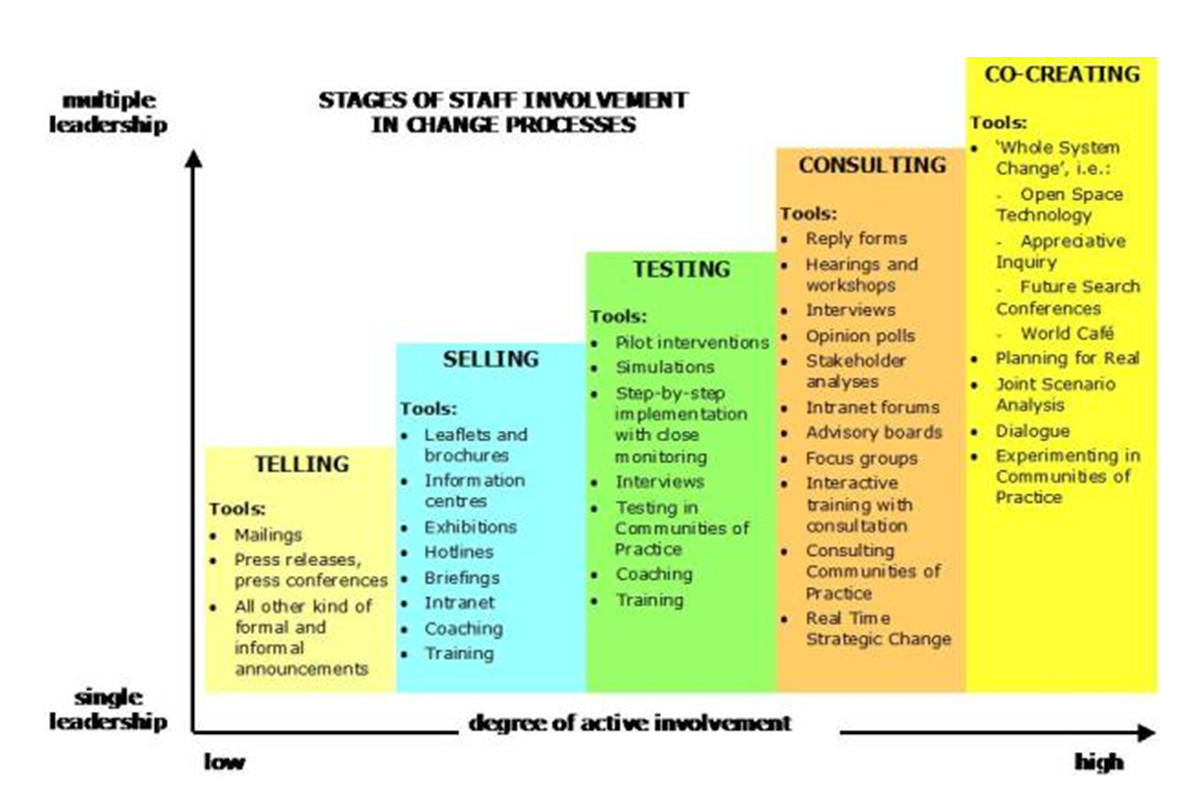

Building a shared vision is typically a developmental process and may consist of various stages.

Every stage of the process should help build both the listening ability of the executive leaders and the leadership capabilities of the rest of the organisation, so that they can move together to the next stage. Your organisation will also move through various stages in setting up shared vision. A specific strategy may be most suitable for a specific phase in your organisational life cycle. Ultimately, one would want to move towards the consulting/co-creating phase, simply because the level of ownership and aligned performance is higher and more sustainable through these processes.

Assess which stage best describes your organisation now:

Telling: The ‘boss’ knows what the vision should be, and the organisation is going to have to follow it. The message: “We’ve got to do this. It is our vision. Be excited about it or reconsider your vision for your career here.”

Selling: The ‘boss’ knows what the vision should be but needs the organisation to buy-in before proceeding. The message: “We have the best answer. Let us see if we can get you to buy in.”

Testing: The ‘boss’ has an idea(s) about what the vision should be and wants to know the organisation’s reactions before proceeding. The message: “What excites you about this vision?” “What doesn’t?”

Consulting: The ‘boss’ is putting together a vision and wants creative input from the organisation before continuing. The message: “What vision do members recommend that we adopt?”

Co-creating: The ‘boss’ and members of the organisation together build a shared vision through a collaborative process. The message: “Let us create the future we individually and collectively want.”

Stage 1: Telling

“We’ve got to do this. It’s our vision. Be excited about it or reconsider your vision for your career here.”

People don’t get to vote. When the boss says, “This is the vision of what the organisation is going to look like two years from now”, people know that if they disagree or if they are caught undermining the change, they jeopardise their career. ‘Telling’ often takes place in a crisis, when the senior managers perceive that some drastic change is necessary.

Tips for mastering the ‘telling’ mode:

- Inform people directly, clearly, and consistently. Letters and videos, if well produced, serve this need; so, do personal speeches, especially if there are opportunities for questions and follow-up.

- Tell the truth about the current reality. Make sure people understand the difficulties of the current status of the company. Generate creative tension/energy. Anything less than the truth can destroy credibility.

- Be clear about what is negotiable and what is not. There may be certain areas where employees have degrees of freedom to influence and others where they literally have no influence.

- Paint the details, but not too many details. A vision, ultimately, needs richness and detail to come to life. Early on, however, don’t fill in too many details, because this may be the organisation’s only changed to make the vision its own.

Stage 2: Selling

“We have the best answer. Let’s see if we can get you to buy in.”

The leader attempts to ‘enrol’ people in the vision, enlisting as much commitment as possible.

Tips for mastering the ‘selling’ mode:

- Keep channels open for responses. For example, follow up briefing sessions/speeches about the vision with break-out groups, so that senior managers can find out how much of the message is ‘selling’.

- Support enrolment, not manipulation. Enrolment is the “…process of becoming part of something only by choice”. You do not enrol others; people can only enrol themselves. If people see the vision is good for them, even if it takes a leap of faith, they will tend to sign on.

- Build on your relationship with the ‘customer’ – your employees. The message in a ‘selling’ effort is: “I’m depending on you for this to work. I value my relationship with you.”

- Focus on benefits, not features. Rather than merely describing the vision, show how it will serve the needs, desires, and situation of your employees.

- Move from the royal ‘we’ to the personal ‘I’. Speak about why it is important to you personally and what special meaning it has for you.

Stage 3: Testing

“What excites you about this vision?” “What doesn’t?”

The leader lays the vision out for testing, not only to find out whether the members support the vision, but how enthusiastically they will accept it and what aspects of it matter to them. Having been asked their opinion, people feel more compelled to discuss and consider the proposed vision.

Tips for mastering the ‘testing’ mode:

- Provide as much information as possible, to improve the quality of the process. Present the vision with all its ramifications spelled out – particularly difficulties.

- Make a clean test. When you ask someone to choose between alternatives A, B and C, design the test as if you really want to know the answer.

- Protect people’s privacy. Design the test so people can answer anonymously, without fear of repercussion – or at least without a penalty for negative answers.

- Combine survey questionnaires with face-to-face interviews. Person-to-person interviews, group interviews or large-scale conferences are highly effective.

- Test for motivation, utility, and capability. Do people want to move toward the vision? Do they think the vision would be useful to them or the organisation?

Stage 4: Consulting

“What vision do members recommend that we adopt?”

Consulting is the preferred stage for a boss who recognises that he or she cannot have all the answers – and who wants to make the vision stronger by inviting the organisation to be the boss’s consultant.

Tips for mastering the ‘consulting’ mode:

- Use the cascade process to gather information. A typical cascade sequence, which may last several months, brings together small teams of ten to fifteen people at every level, starting with the top of the organisation. The cascade process works best when responsible managers run their teams, but a committed group of facilitators are available as resources.

- Build in protection against distortion of the message. Start each meeting with a videotaped message. However, when the vision changes because of the consulting process, the video should be updated.

- Gather and give results. Collect anonymous written comments from participants after every consulting session. This ensures that people who do not want to speak openly can nonetheless be heard.

- Do not try to tell and consult simultaneously

Stage 5: Co-creating

The co-creating stage is obviously the ultimate way of creating a shared vision. It can be achieved as follows:

Start with a personal vision: When a shared vision starts with a personal vision, the organisation becomes a tool for people’s self-realisation rather than a machine they are subjected to. People begin to stop thinking of the organisation as a thing to which they are subservient. Only then can they wholeheartedly participate in guiding its direction.

Treat everyone as equal: Everybody has an equal say and an equal vote in what the vision should be. Status differences should be discouraged altogether.

Seek alignment, not agreement: The temptation will be strong to paper over differences for the sake of reaching resolution and producing a coherent output. Teams should discourage this. Instead, they should use team learning practices such as skilful discussion and dialogue to look for the assumptions beneath the disagreement and see what mental models have led to this irreconcilable view.

Encourage interdependence and diversity among teams: When team members begin talking about their vision, avoid telling them what other teams have said. Rather ask each team first: “What do we really want?” Once the team’s vision has been articulated, then members who also belong to other teams can later serve as communicating agents. Over time, teams become curious about each other’s visions and two or more teams may discover a strategic value in meeting together, comparing notes and creating a shared vision in tandem.

Avoid sampling: Avoid talking only to a sample of people, due to time and financial constraints. Everybody must have an equal opportunity to express how they see the vision for their part of the organisation.

Have people only speak for themselves: Participants should not be allowed to let their assumptions about how other people may react to their vision interfere with the process. They should be honest in what they want and what they would like to see.

Expect and nurture reverence for each other: When a real diversity of opinions occurs in a group, a reverence for each other’s vision will often take hold.

Consider using an interim vision to build momentum: A brief, rough and intuitive vision will give team members an initial point of reference. If it comes from higher in the hierarchy, do not distribute it in a memo. Refrain from revealing it right away at team meetings. Wait until the team members have started to get some clarity about their own vision. Only then the interim vision can be made available, which can then be aligned with what the team has in mind.

Focus on the dialogue, not just the vision statement: Visions often translate into vision and purpose statements, which seem cryptic to outsiders, but have enormous meaning for the people who struggled to craft each word, so that everyone can sign off on them and feel the statement is meaningful. The process is more important than the product. Participants actively instil meaning and inspiration into the words and give them symbolic value. The words on its own mean nothing. That is why the test of a vision is not in the statement, but in the directional force it gives the organisation.

In building a vision, Stephen Covey’s Habits 2, “Begin with the end in mind”, also provides valuable ideas. According to Covey, to begin with the end in mind means to start with a clear understanding of your destination. It means to know where you are going so that you better understand where you are now and so that the steps you take are always in the right direction. The extent to which you begin with the end in mind often determines whether a business succeeds.

Covey captures the essence of a deep shared vision as follows: “…(it) creates a great unity and tremendous commitment. It creates in people’s hearts and minds a frame of reference, a set of criteria or guidelines by which they will govern themselves. They don’t need someone else directing, controlling, criticising or taking cheap shots. They have bought into the changeless core of what the organisation is about.”