No matter how technically or administratively perfect a proposed change may seem, people will make it or break it. Individual and group behaviour following an organisational change can take many forms, as outlined on the continuum below:

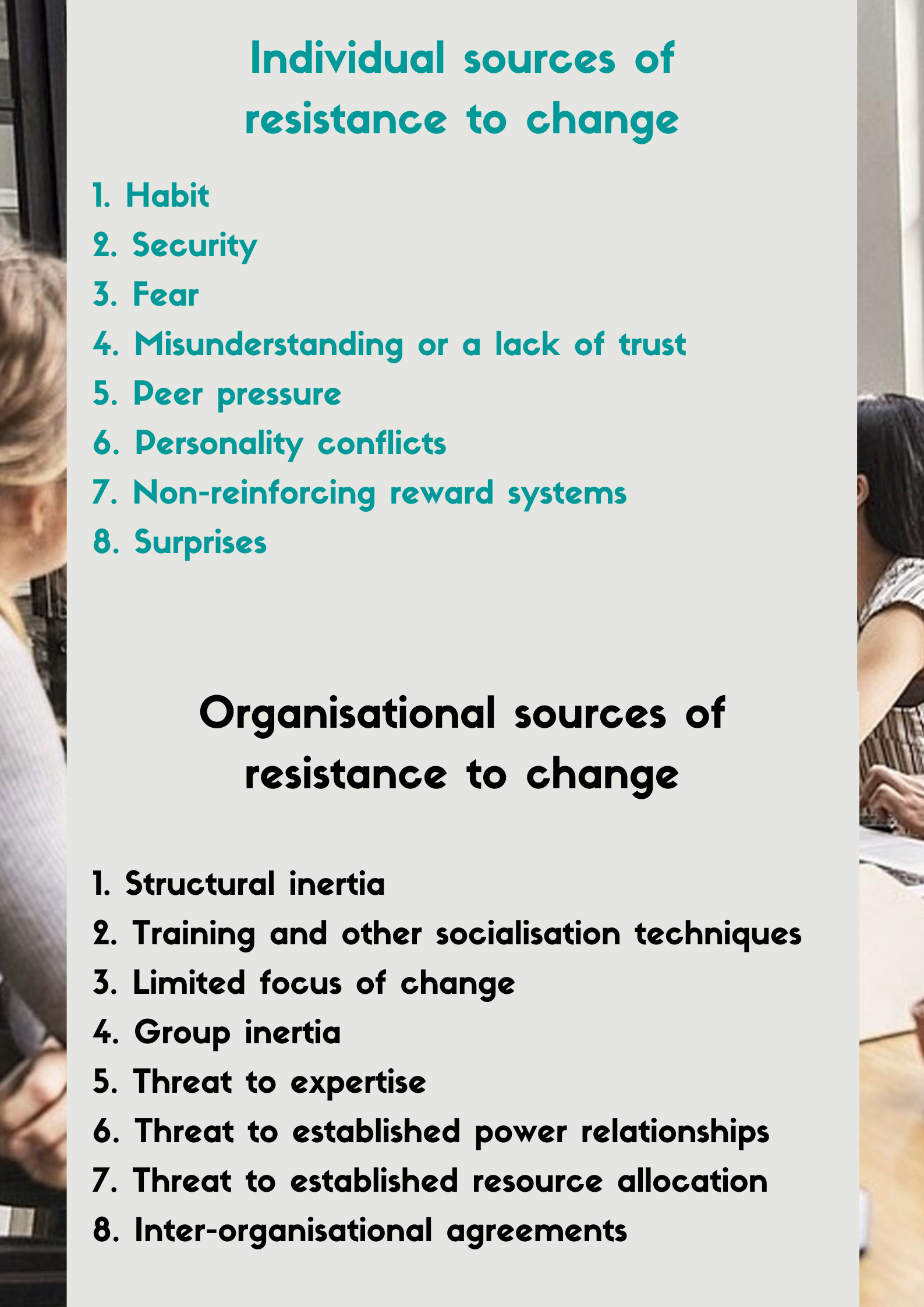

Resistance to change can be regarded as an emotional/behavioural response to real or imagined threats to an established work routine. Sources of resistance can be categorised by individual and organisational resistance; however, these sources often overlap in change situations.

Individual Resistance

Individual sources of resistance to change reside in basic human characteristics such as perceptions, personalities and needs. Let us consider a number of reasons why individuals may resist change:

Habit: Humans are creatures of habit. Individuals develop certain habits over time in order to make their lives and environment as convenient and orderly as possible. Change will force people to drop certain habits and this may seem threatening to them.

Security: People often resist change, because they have a perception that they will lose something of value to them; their sense of safety and security is threatened. A drop in salary as a result of the introduction of a new performance management scheme can be a major concern for some people.

Fear: Change introduces uncertainty and a degree of fear. People fear failure if a change may require them to acquire new skills; move to a different department; getting accustomed to a new leader, system, process, and so on. The ambiguity and uncertainty of certain change situations result in resistance.

Misunderstanding or a lack of trust: People resist change when they do not understand its implications, which may occur because of misunderstanding or a lack of trust. Individuals are also sometimes guilty of selective information processing, meaning that their own perceptions lead to a lack of trust in any change proposed by management.

Low tolerance: Some people have a low tolerance for any change and may resist a change even when they think it is a good one. A person may resist the opportunity to be transferred to a better paying position in another city, simply because they believe the risk is too high. The risk in this case is the possibility that he will not be able to make new friends; get along with new colleagues; or fit in with his new environment.

Peer pressure: Peers often apply pressure to resist change. Although a person may not directly be affected by change, it may still be resisted to protect the interests of friends and co-workers.

Personality conflicts: Personality clashes between an individual and change agents can breed resistance. It can sometimes be regarded as pure stubbornness or spitefulness.

Non-reinforcing reward systems: If an individual can’t foresee any positive rewards for changing, resistance sometimes comes natural. An employee is unlikely to support a change effort that is perceived as requiring longer hours with more pressure without additional reward.

Surprises: People do not react favourably to surprises. If the change is sudden, unexpected or extreme, resistance may almost be a reflex reaction.

Organisational Resistance

In general, most organisations are very conservative in nature and are designed to restrict innovation. Organisations are designed and structured in such a way as to ensure stability and consistency, and as a result, some built-in defences against change are characteristic. Major sources of organisational resistance as identified by Robbins include:

Structural inertia: Organisations are structured to ensure stability and various rules, regulations, policies and procedures exist to create a strategic fit. Selection processes conform to the organisational fit. Newly recruited employees are then shaped and directed to act and behave in a certain way. Training and other socialisation techniques reinforce specific role requirements and skills. When the organisation is confronted with change, this structural inertia acts as a counterbalance to sustain stability.

Limited focus of change: Organisations consist of various sub-systems. When a change occurs in one, it will affect the others. A change in technological processes, without a modification to the organisational structure to match, may result in the technology not being accepted. Limited changes in sub-systems tend to get nullified by the larger system.

Group inertia: Group norms typically dictate individual behaviours and actions. Should management suggest certain changes in the job of an individual, he/she may be willing to accept these changes, but if union norms dictate resisting any unilateral decisions by management, he/she is likely to resist.

Threat to expertise: The expertise of specialised groups in an organisation may be threatened by changes in organisational patterns. Salespeople may feel threatened should management decide to invest heavily in Internet advertising and shopping facilities, and strongly resist such a decision.

Threat to established power relationships: Any redistribution of decision-making authority can threaten long-established power relationships within the organisation. The introduction of participative decision-making or self-managed work teams is the kind of change that is often seen as threatening by supervisors and middle managers.

Threat to established resource allocation: Groups in an organisation controlling sizable resources often see change as a threat. A change may mean a reduction in their budgets or a cut in their staff size. In other words, those that benefit most from the current allocation of resources often feel threatened by changes that may affect future allocations.

Inter-organisational agreements: Inter-organisational agreements can create obligations that limit future options. Labour contracts are good examples. Other contracts and agreements can also create obligations for management. Change agents may find their plans delayed due to arrangements with competitors, commitments to suppliers and promises to contractors. Breaching these contracts and agreements may have serious financial implications.