Click here to view a video that explains how to evaluate sources.

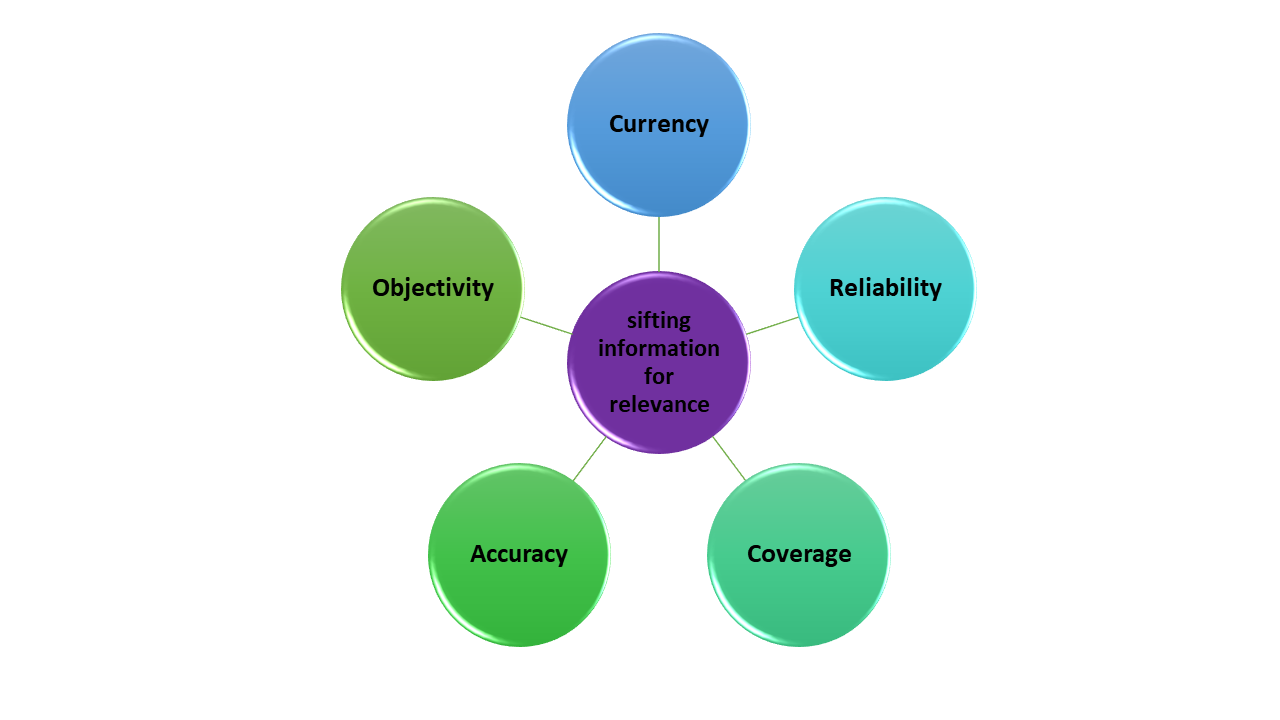

Currency

How up to date is the information source? Does it cover recent developments? Has it been updated (in the form of a new edition or update) to deal with changes in knowledge or corrections? This is more important in some areas (e.g. the sciences) than others (e.g. literature).

Be aware that dates can be misleading: Books – It can take up to two years for a book to be published, so the information in a 1999 book may already be out of date. Some dates represent the year a book was republished (as a paperback, or after being out of print for some years). Journals – Journal articles are usually printed more quickly than books, but there can still be a delay of over a year (depending on the journal) before you see it, especially considering that many journals are sent to Australia by sea. Web pages – Many are updated constantly, but there is no guarantee that the date given (if given at all) is accurate.

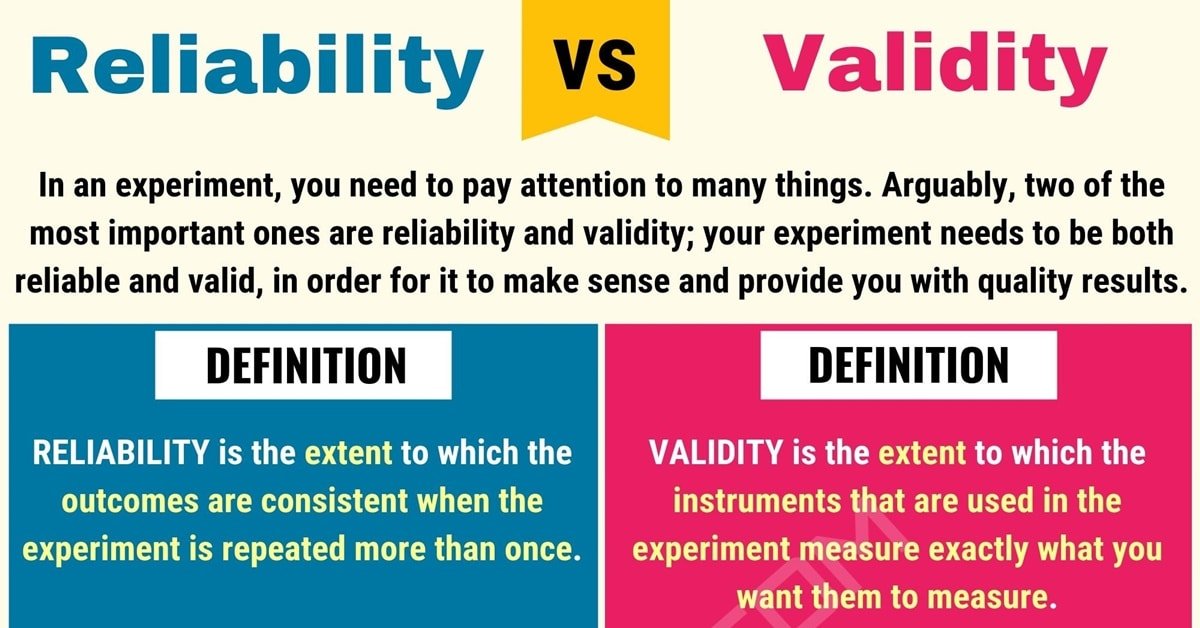

Reliability

Is it clear who is the author? What are the author's credentials? What qualifications do they have for writing the piece? Are they backed by a reputable or traceable organisation? Information that does not conform to these criteria is not necessarily flawed or unreliable, but you should use it with caution. Remember that the web in particular is open to anyone who can write anything they want. Look carefully for evidence of bias, omissions or unsupported statements of "fact".

Coverage

When considering whether an information source is going to be useful you need to look at the range it covers. You also need to consider whether it consists of primary or secondary source material. Primary material contains new information or a new interpretation of previously known information. Secondary material is interpretation and comment on primary material by others. Does it have the detail you need? Does it supplement other sources you have read or merely confirm information you already knew? You may need to cover a variety of different viewpoints.

If your essay is on a broad topic don't try to absorb every detail you can find. Start with an article from an encyclopaedia or find a book that gives a general overview of your topic. When you need detailed information, an academic article is more likely to help you than a general overview.

Click here to view a video that explains the types of information sources.

Accuracy

Can you check the information elsewhere? Are the sources of any facts clearly and correctly listed? Do you have faith in the spelling and other proof reading aspects of the work? Key dates, facts and other figures should always be verified from alternative sources to ensure that they are correct. Check that they come from the source cited in the work. An incorrect citation may imply that the facts are not correct. While spelling and proof reading may seem trivial, consistent misspellings may mean that facts and figures are also typed or printed incorrectly. They may also imply that the information has not been thoroughly checked for inaccuracies.

Objectivity

This is the most difficult area to judge because virtually all sources are subjective in some way. Good academic work considers all viewpoints and uses material from many sources to show a depth of research and consideration of all aspects of a question. Some tips for recognising bias in information sources:

- Use of emotive or derogatory language

- Omissions in the information presented

- Contradictions to other material you have read

- Viewpoints that seem extreme to you

- You may disagree with some sources, but you need to show your familiarity with them, and demonstrate why you disagree with them.

Click here to view a video that explains how to evaluating information objectivity.

Further questions to ask yourself:

- Is the article relevant to the current research project? A well-researched, well written, etc. article is not going to be helpful if it does not address the topic at hand.

- Ask, "is this article useful to me?"

- If it is a useful article, does it:

- support an argument

- refute an argument

- give examples (survey results, primary research findings, case studies, incidents)

- provide "wrong" information that can be challenged or disagreed with productively.