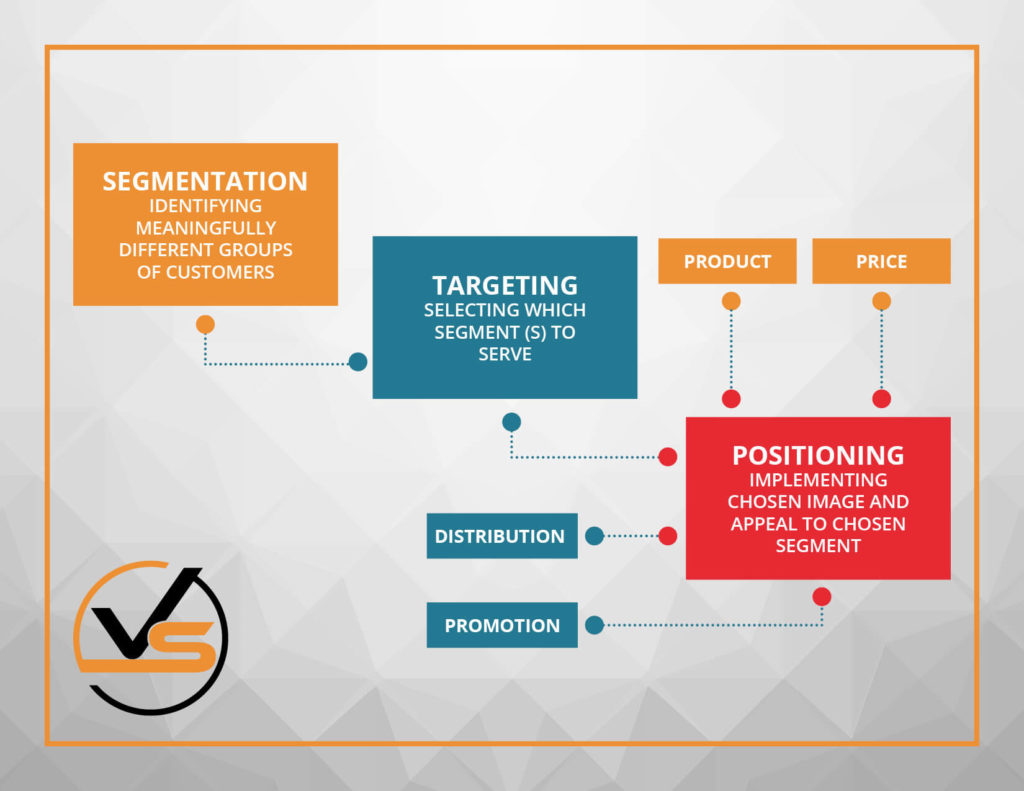

Segmentation, targeting, and positioning together make up a three-stage process:

- determine which kinds of customers exist, then

- select which ones we are best-off trying to serve, and finally,

- implement our segmentation by optimizing our products/services for that segment and communicating that we have made the choice to distinguish ourselves that way.

Segmentation involves finding out what kinds of consumers with different needs exist. In the auto market, for example, some consumers demand speed and performance, while others are much more concerned about roominess and safety. In general, it holds true that “You can’t be all things to all people”, and experience has demonstrated that businesses that specialize in meeting the needs of one group of consumers over another tend to be more profitable.

Generically, there are three approaches to marketing.

Undifferentiated strategy, all consumers are treated as the same, with businesses not making any specific efforts to satisfy particular groups. This may work when the product is a standard one where one competitor really can’t offer much that another one can’t. Usually, this is the case only for commodities.

Concentrated strategy, one firm chooses to focus on one of several segments that exist while leaving other segments to competitors. For example, Southwest Airlines focuses on price sensitive consumers who will forego meals and assigned seating for low prices.

Differentiated strategy: Most airlines offer high priced tickets to those who are inflexible in that they cannot tell in advance when they need to fly and find it impractical to stay over a Saturday. These travellers, usually business travellers, pay high fares but can only fill the planes up partially. The same airlines then sell some of the remaining seats to more price sensitive customers who can buy two weeks in advance and stay over.

Segmentation calls for some tough choices. There may be many variables that can be used to differentiate consumers of a given product category; yet, in practice, it becomes impossibly cumbersome to work with more than a few at a time. Thus, we need to determine which variables will be most useful in distinguishing different groups of consumers.

In the next step we decide to target one or more segments. Our choice generally depends on several factors.

- Firstly, how well are existing segments served by other manufacturers? It will be more difficult to appeal to a segment that is already well served than to one whose needs are not currently being served well.

- Secondly, how large is the segment, and how can we expect it to grow? (Note that a downside to a large, rapidly growing segment is that it tends to attract competition.)

- Thirdly, do we have strengths as a company that will help us appeal particularly to one group of consumers? Businesses may already have an established reputation. While McDonald’s has a great reputation for fast, consistent quality, family friendly food, it would be difficult to convince consumers that McDonald’s now offers gourmet food. Thus, McDonald’s would probably be better off targeting families in search of consistent quality food in nice, clean restaurants.

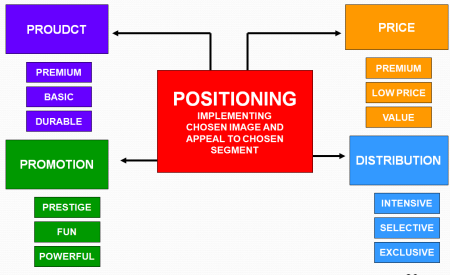

Positioning involves implementing our targeting. For example, Apple has chosen to position itself as a maker of user-friendly computers. Thus, Apple has done a lot through its advertising to promote itself, through its unintimidating icons, as a computer for “non-geeks”. The Visual C software programming language, in contrast, is aimed a “techies”.

Michael Treacy and Fred Wiersema suggested in their book The Discipline of Market Leaders (1993) that most successful businesses fall into one of three categories:

Operationally excellent businesses, which maintain a strong competitive advantage by maintaining exceptional efficiency, thus enabling the firm to provide reliable service to the customer at a significantly lower cost than those of less well organized and well-run competitors. The emphasis here is mostly on low cost, subject to reliable performance, and less value is put on customizing the offering for the specific customer. Wal-Mart is an example of this discipline. Elaborate logistical designs allow goods to be moved at the lowest cost, with extensive systems predicting when specific quantities of supplies will be needed.

Customer intimate businesses, which excel in serving the specific needs of the individual customer well. There is less emphasis on efficiency, which is sacrificed for providing more precisely what is wanted by the customer. Reliability is also stressed. Nordstrom’s and IBM are examples of this discipline.

Technologically excellent businesses, which produce the most advanced products currently available with the latest technology, constantly maintaining leadership in innovation. These businesses, because they work with costly technology that needs constant refinement, cannot be as efficient as the operationally excellent businesses and often cannot adapt their products as well to the needs of the individual customer. Intel is an example of this discipline.

Treacy and Wiersema suggest that in addition to excelling on one of the three value dimensions, businesses must meet acceptable levels on the other two. Wal-Mart, for example, does maintain some level of customer service. Nordstrom’s and Intel both must meet some standards of cost effectiveness. The emphasis, beyond meeting the minimum required level in the two other dimensions, is on the dimension of strength.

Repositioning involves an attempt to change consumer perceptions of a brand, usually because the existing position that the brand holds has become less attractive. Sears, for example, tried to reposition itself from a place that offered great sales but unattractive prices the rest of the time to a store that consistently offered “everyday low prices". Repositioning in practice is very difficult to accomplish. A great deal of money is often needed for advertising and other promotional efforts, and in many cases, the repositioning fails.

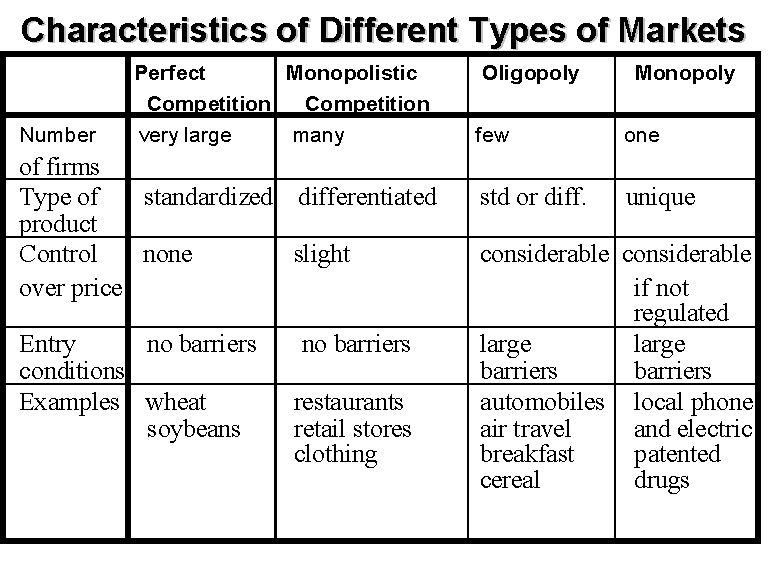

To position your business effectively requires a basic knowledge of market types. A summary of market types is included in the next table:

In market economies, there are a variety of different market systems that exist, depending on the industry and the companies within that industry. It is important for small business owners to understand what type of market system they are operating in when making pricing and production decisions, or when determining whether to enter or leave a particular industry.

Perfect Competition: Perfect competition is a market system characterized by many different buyers and sellers. In the classic theoretical definition of perfect competition, there are an infinite number of buyers and sellers. With so many market players, it is impossible for any one participant to alter the prevailing price in the market. If they attempt to do so, buyers and sellers have infinite alternatives to pursue.

Monopoly: A monopoly is the exact opposite form of market system as perfect competition. In a pure monopoly, there is only one producer of a particular good or service, and generally no reasonable substitute. In such a market system, the monopolist is able to charge whatever price they wish due to the absence of competition, but their overall revenue will be limited by the ability or willingness of customers to pay their price.

Oligopoly: An oligopoly is similar in many ways to a monopoly. The primary difference is that rather than having only one producer of a goods or service, there are a handful of producers, or at least a handful of producers that make up a dominant majority of the production in the market system. While oligopolists do not have the same pricing power as monopolists, it is possible, without diligent government regulation, which oligopolists will collude with one another to set prices in the same way a monopolist would.

Monopolistic Competition: Monopolistic competition is a type of market system combining elements of a monopoly and perfect competition. Like a perfectly competitive market system, there are many competitors in the market. The difference is that each competitor is sufficiently differentiated from the others that some can charge greater prices than a perfectly competitive firm. An example of monopolistic competition is the market for music. While there are many artists, each artist is different and is not perfectly substitutable with another artist.

(Monopsony: Market systems are not only differentiated according to the number of suppliers in the market. They may also be differentiated according to the number of buyers. Whereas a perfectly competitive market theoretically has an infinite number of buyers and sellers, a monopsony has only one buyer for a particular good or service, giving that buyer significant power in determining the price of the products produced.)